Behind the Veil

Competitive Morality Across Cultures

Rules are everywhere. Rules include the rules of the game—collect $200 when you pass Go—rules enshrined in law—don’t take anyone else’s $200—and moral rules— don’t hit your brother because he beat you at Monopoly. All three of these areas—games, law, and morality—regulate what you may and may not do and what happens if you break the rule.

There are two kinds of rules.

The first kind of rule, which I’ll call universal, affects everyone equally. The Monopoly rule that gives $200 for passing Go applies identically to all players. No one knows who will benefit in any particular game from the rule first or most: it’s not tailored to any one person or group. This symmetry had led my former student and me to call such rules Rawlsian—partly to flex our philosophical credentials, and partly because the label gets the idea across: These are the kinds of rules that people would agree to before they know their starting position in the game—behind what John Rawls called the “veil of ignorance.”

In hindsight, I somewhat regret the terminology. Referring to the great philosopher might have sacrificed clarity for the aura of intellect, a sin far too common in the academy. So here I’m calling these rules universal. That label has its own problems, but the basic idea is simple: a universal rule is one that applies in the same way to everyone in the game/jurisdiction/culture. An example is the rule against murder. Because everyone can both be a killer and be killed, the rule applies to everyone.

Not every rule/law/moral norm is universal.

Let’s take a rule in the news recently, rent control. Rent control laws create price ceilings, restricting how much a landlord may charge a tenant.1 This law emphatically does not affect everyone equally. It negatively affects landlords: Rent control makes people who own properties to rent worse off, reducing revenue from their properties and making their properties less valuable. (Just ask landlords in Argentina.)

On the other hand, rent control makes current tenants better off. It reduces how much they must pay the landlord.2

It should be clear that when it comes to the price charged by landlords, the game is zero sum. Each dollar of rent control means one less dollar for the landlord and one more dollar for the tenant.

And like all zero-sum games, it’s inherently competitive. Landlords and tenants are on opposing sides of a rule that shifts money from one group to the other. The controversy over rent control isn't just a philosophical debate about the proper role of government. The debate is sometimes framed that way, but the stakes are on-the-ground practical, to do with people’s interests. Landlords and tenants have conflicting interests, and this law decides who wins because governments can enforce the law with police, courts, and prisons.

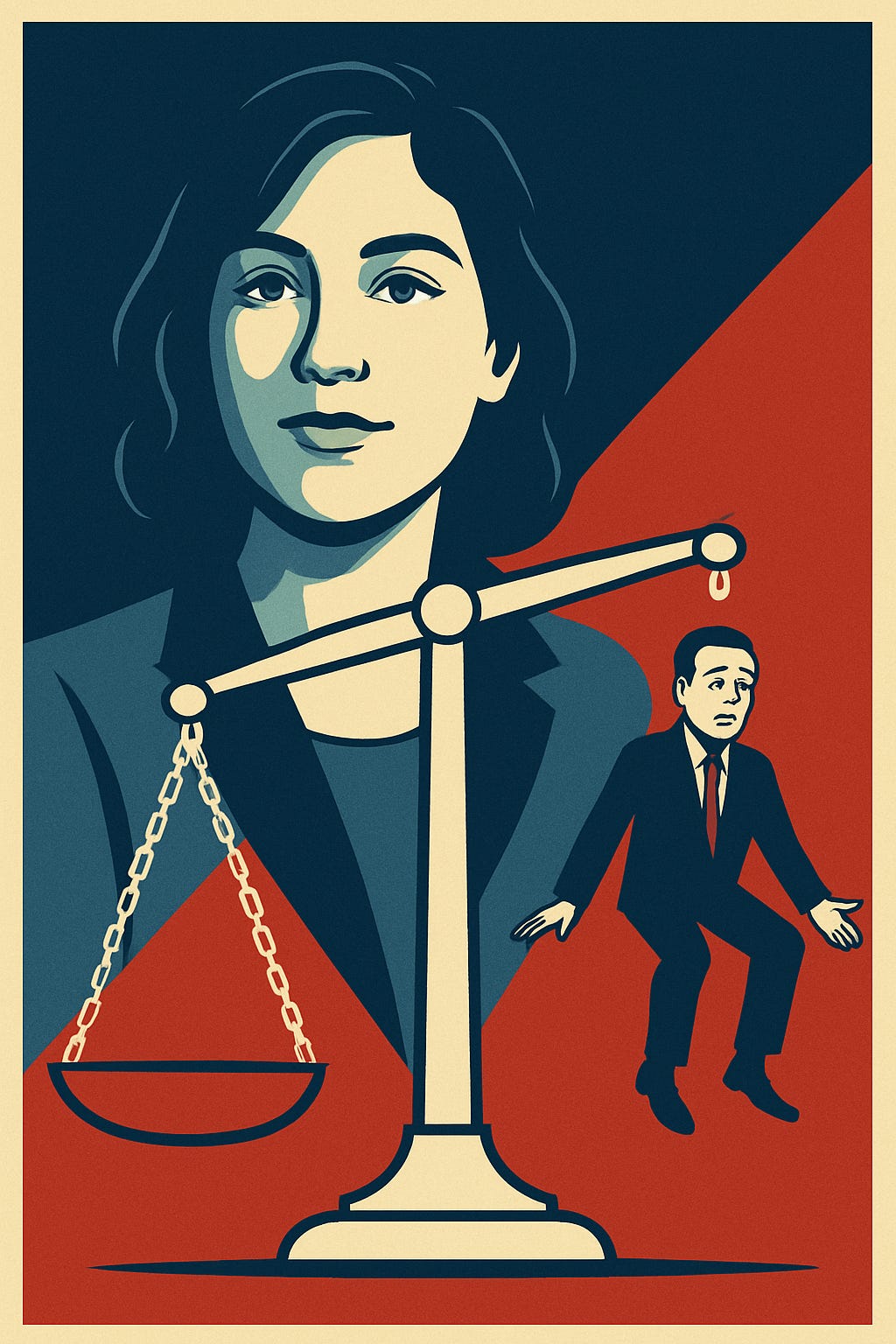

These rules are not at all Rawlsian or universal. Behind the veil of ignorance, you don’t really know if you want the rule or not. It depends what role you will play, landlord or renter. That’s why I’ll call this second type of rule “competitive.”3 Competitive rules—whether legal, moral, or procedural—create winners and losers, benefiting one set of people while imposing costs on another. And because the stakes are real, these rules generate real conflict over what the rule will be. Elections often settle these disputes.

A crucial point to note is that when people defend such rules, it can be difficult to determine the motive. Most people don’t defend rules that benefit them or people like them by saying, I favor rent control because I, a tenant, will save money and I like money. They will, more or less always, offer a different reason for their support, often to do with religion or philosophy. I favor rent control because it reduces wealth inequality which is great!

This is an important point because there are any number of other domains in which the rules make some better off and some worse off. When I was completing my Master of Public Administration degree at the Fels Institute of Government, I took a great course about administrative law and chose to write my final paper on the rules governing Uber and Lyft, known as transportation network carriers. In places such as Chicago, New York, and, my focus, California, taxi companies lobbied for laws—or interpretation of existing laws—to prevent these new companies from operating, especially in the most lucrative areas, such as airports. This lobbying was transparently motivated by self-interest, as taxi owner and drivers did not want to lose their monopoly, which kept their costs low and prices high.4 In most places, taxis lost and transportation network carriers—and consumers—won.

Minimum wage laws are worse for business owners but better for (some) workers. Affirmative action policies are better for the groups they benefit, worse for people not in those groups. There are any number of similar cases in which the rules benefit some at a cost to others, including tariffs, copyright laws, and so forth. In some cases, the debate is complex and the temperature so high that it can be hard to see where the various parties’ interests lie, as in the case of abortion. And, at the risk of touching the third rail, the rule about who competes with whom can literally change winners to losers and losers to winners.

Generally, to return to John Rawls, one good way to check if a rule is universal or competitive is to use his gambit, the veil of ignorance. Ask yourself if you would favor a given rule or law if you didn’t know what role you occupied in society before you made your choice. Behind this veil of ignorance, for sure you want the rule against murder. That one’s easy. If you don’t know if you’re an employee or employer, do you favor a $20/hour minimum wage? That’s a little harder. The difficulty you have deciding is a guide that you’re considering a competitive rule rather than a universal one.5

The Mating Minefield

Love, as Pat Benatar wisely noted, is a battlefield.

As David Buss, his collaborators, and others have explained in some detail, men and women have different—and often incompatible—mating strategies.

Because there is competition, mating is like the rental market in that there are zero sum aspects but also cooperative aspects. After two people have a child, for instance, they both have an interest in the welfare of that child.6 Plenty of room for cooperation.

But not everything about mating is cooperative. Thanksgiving can’t be spent at both families’ relatives homes. Sex outside of the relationship is either allowed or forbidden, and the respective partners might well have different interests in terms of which regime holds. The rules surrounding courtship, mating, and relationships are not remotely all universal. Some are competitive.

Briefly, human females, who, like other mammals, invest more in offspring, tend to be choosier than males, preferring a monogamous mate who is willing and able to invest in her offspring, and prefer a partner who is also able to do so in virtue of his access to resources. To achieve these ends, human females benefit from having the opportunity to choose who they mate with and from being able to advertise the qualities the other sex wants. Rules enforcing monogamy help them hit evolutionary homeruns in the baseball game of fitness, monopolizing the resources of their mate. Or, to put it the other way, rules banning polygamy are huge wins for women.7

Human males, also like other mammals, invest less in offspring and, as a consequence, are designed to desire more mates, especially those mates who give the cues associated with the greatest reproductive potential, explaining the male preference for youth and beauty. To achieve these ends, human males benefit from having the opportunity to choose who they mate with, to choose how many people they mate with, and to advertise the features that make them appealing to the (choosy) mates they desire.

That is the two paragraph summary of about fifty years of work on mate choice from an evolutionary perspective, so it’s a bit imprecise, but good enough for the present purpose.8

I recently read Infidel by Ayaan Hirsi Ali, in which the author traces her story, starting in a traditional Muslim family in Somalia, continuing in Holland where she is exposed to the alien culture of the West, eventually leading to her leaving Islam and being elected to the Dutch Parliament.

I was somewhat aware of the norms that govern sex and sexuality in Muslim cultures, but in Infidel, Hirsi Ali provides a more detailed, thorough, and intimate first-person look.

And that got me to thinking about the very different basket of norms that she discusses, and how they intersect with the notion of competitive morality.

The collection of rules that Hirsi Ali labors under before moving to Holland could hardly be more obviously norms that benefit certain men, especially high status men, at the expense of women.

These norms take away a woman’s most important tool, her choice of a mate. This choice is made by her family, usually her father. Now, to some extent their interests are aligned, but as any student of evolution knows—as does anyone who has any experience with their parents’ views on who they should date—these interests are not perfectly aligned. It is hard to make good, careful decisions about your long-term mate when you yourself are prevented from making the choice, on pain of serious punishment.

Much came between Hirsi Ali and her father that caused their inevitable rift. After all, he held the values of traditional Islam, and Hirsi Ali came to reject these values. But the proximate cause of the final schism between the two of them was Hirsi Ali’s decision not to marry the man that her father had selected. When this happened, she was, not without some justice, concerned for her very life. That indicates how serious this rule is. Breaking it is a capital offense.

It is not just the norm regarding mate choice that works against women in this context. As discussed at length in the scholarly literature on mating—women attract mates by advertising the traits that men desire, including markers of youth, their secondary sexual characteristics, and so on. This tactic is denied women in the communities in which Hrisi Ali traveled. First, women’s movements were carefully controlled, with many rules dictating where they could go, who must accompany them, and so on. Further, additional rules specified that women must be covered, more or less head to toe, again on pain of punishment, eliminating any chance to influence men’s decisions with their physical features. These rules were not restricted to vision: additional rules prohibited the use of perfumes and fragrances, removing another arrow from women’s quiver, effectively prohibiting sexiness.

Even after entering into a long-term mate-ship, women’s strategies were thwarted, as the rules allow men to take multiple wives, if they are able, with prior wives having, unsurprisingly, no voice in the decision. This rule undermines something a well-designed self-interested female mind should be expected to seek with diligence: a monopoly on a mate’s investment.

On every front, these competitive rules tilt the game in favor of high status men to the detriment of women and low status men.

It’s easy to see that these are competitive rules because they are definitely not universal. It seems likely to me that no one who did not know that they were going to be a man or a woman, high status or low status, would endorse these rules. It’s painfully obvious that these rules are in place to advance the interests of men at the expense of women.

Of course, as indicated above, the explanation for supporting these rules is couched in the language of religion. These rules are enshrined in the holy book, and that is the reason men say they support them.

The enforcement of these rules is similarly emphatically not universal. In one astounding passage, Hirsi Ali describes what her grandmother says a young Ayaan should do if she finds herself in a position in which she might be raped. The instructions are to say that god is watching but, if the assault occurs despite this reminder to the assailants, she bears the blame and will suffer life-destroying consequences, including ostracism or even death. In this moral space, there are harsh punishments not only for breaking moral rules, such as clothing choices, but for being the victim of an assault.

These rules are not the only way in which women are tormented. Hirsi Ali describes the appalling practice of mutilating women’s sexual organs as they approach adolescence. This is to say nothing of the subordinate role women play in essentially every context she discusses.

The deck is stacked against women in another way: their testimony is given only half as much weight as a man’s. Therefore, in the case of a dispute between a man and a woman, with the man claiming, say, that sex was consensual, the woman’s testimony would be discounted by half.

Supporting such rules, in my view, is just clearly and obviously ethically bankrupt. These are terrible, discriminatory rules, flying in the face of Enlightenment values. And taking refuge in religion as the source of these rules, to my eye, does not make the person backing them any less ethically suspect.

Things are obviously much more pleasant from the man’s perspective.9 Men retain the ability to choose, can leverage their wealth and status to obtain multiple mates, and have no restrictions in terms of advertising or attracting potential mates. And, of course, if conflict arises, by a two to one margin, arbitrators to a conflict are to Believe Men.

Totting up all the rules that govern sex and sexuality, in this particular cultural norm space, essentially all of the competitive moral rules favor men. To put it bluntly, in Somalia, as in much of the Muslim world, men won the fight over moral norms and women lost.

Not every culture has, of course, landed on the same rules. To see the variety, let’s ask what the opposite moral regime would look like, a world in which women won the battle over the competitive rules.

In this regime, women would choose their mates, of course. Men would be unable to signal, or leverage, wealth and status to acquire mates. Their word would be worth even less than half of a woman’s, perhaps thoroughly discounted.

Of course no such world exists, and most cultures wind up somewhere in the middle. Still, it should be clear that the most defensible rules would be the ones that are closest to universal, the norms that would be chosen behind the Rawslian veil. Both can choose. Both can make use of their mating strategies and tactics. Both are equally believed.

Where do cultures wind up?

One place that provides an interesting window is when the mating strategies are pared down to the bare bones: the exchange of money for sex.

Historically, in many places and times, including in the United States throughout much of its history, only the female strategy—the selling of sex—was moralized and penalized through the force of law. While buying sex was also illegal in many times and jurisdictions, enforcement, and social censure, focused on women. This regime is not uncommon historically, and was prevalent in much of the West in the 19th and 20th centuries. Men were by and large making the laws and men, by and large, won the norm fight.

In contrast, consider the Swedish Sex Purchase Act, which criminalized the male strategy—the buying of sex—while the other side of the transaction, the female strategy, was decriminalized. Other countries, including Canada, Ireland, and Iceland, would eventually follow suit.10

These two regimes nicely illustrate how norms change to undermine and punish the strategy of one side or the other.

A problem with moral debates is that when we support a rule that benefits us, we often claim that we are supporting that rule for a good, ethical reason. In some cases, we might even believe it. It seems plausible to me that the men in Hirsi Ali’s life genuinely believe that the top moral duty is to impose the rules in the Quran. Plausible. It’s also plausible that they could find justification for other moral regimes in the book and choose not to because they enjoy the benefits of the current regime, including the rules that allow them to control and abuse the women in their lives, including sexually, with no negative consequences.

The ease with which people claim noble motives for their support of rules is exactly why we have to step behind the veil of ignorance and ask if we really would support the rule if we didn’t know what role we played in society.

Behind the veil of ignorance, not knowing if you were the singularly beautiful Helen of Troy or not, would you support the duty to, well, keep your face hidden behind the veil?

If you’re supporting rules that just happen to benefit people like you—because reasons, including past wrongs, currently fashionable ideology, or the signals the support sends—be sure to take a moment to put on the veil of ignorance and reflect.

These laws vary, often putting a cap on rent increases. Nothing turns on the details.

I don’t really want or need to get into it—here is one recent treatment—but these rules also harm potential tenants, e.g., those who would be willing to pay the market price for the rent-controlled unit. That is just to say that competition is everywhere.

Elsewhere, we referred to these as “strategic.” I am trying a different term here because I have struggled to get these ideas across, so I’m rebranding. Also, the very notion of “competitive moral rules” might annoy people who take morality to mean “cooperation,” so that is like an added bonus.

Prices in this context are complicated because fares are generally set by the relevant regulatory agency. I also don’t want to go down this rabbit hole. It’s complicated.

Is there a third sort of rule? Suppose you don’t know if you’re going to be in a position in which you have spare capital to lend or you have need of capital. How would you feel about rules forbidding lending money at interest? In both cases, you would oppose them. So there are some rules that make all players worse off. Yet for some reason such rules spring up all the time. Mysterious. Just absolutely mysterious. Especially mysterious if morality is for cooperation. Why is everyone agreeing to a rule that undermines cooperation? Did I mention this is mysterious?

Rental contracts allow landlords and tenants to cooperate, despite the conflict. Each party wants to commit to the contract. The landlord benefits by reducing the chance they need to find another tenant and the tenant benefits from reducing the ability of the landlord to increase the rent during the term. From this we see that relationships that have some competition also allow cooperation.

It’s complicated. Women who would do better as the 2nd mate of a high quality male are worse off in the regime. So the win here is really for a subset of all women. The women who are worse off depends on the distribution of mate quality. For the technical details, see the polygamy threshold model in the behavioral ecology literature.

See Don Symons’ book The Evolution of Human Sexuality for the OG, and see David Buss’ work more recent accounts.

Again, this claim is slightly more complicated than I am putting it. These rules can undermine the mating strategy of low status males because polygynous males are multiply mated. So it’s not quite as simple as men and women. Still, even if low status men lose to some extent in this regime, that does not mean that women lose any less.

For the record, my view on this is grounded in my libertarianism.

*Benatar

I disagree with your take about the idea that the veil of ignorance lets you decide if the rule is competitive as you define it. As I see things, there are more employed people than employees, more tenants than landlords, so even if you aren't 100% certain, by statistical reasoning you should still prefer the rule that is favourable to the more people (possibly weighting in some way so as to avoid extreme utilitarian degenerate states like one person suffering for the whole humanity).

"Ask yourself if you would favor a given rule or law if you didn’t know what role you occupied in society before you made your choice" well I'd prefer minimum wages and controlled rents for probabilistic reasons.