Is Schooling a Damaging Evolutionary Mismatch?

A guest post by Michael Strong, University of Austin

As The Living Fossils approaches its one-year anniversary on June 9th, we are thrilled to have our first guest post. Michael Strong is the Executive Director of the Adolescent Flourishing Initiative at the University of Austin. (You can subscribe to his Substack here.) If you or someone you know is interested in contributing, please let us know. In the meantime, enjoy today’s thoughts from Michael Strong.

In the 1990s, a cohort of about 40 orphaned young elephants were transported to Pilanesberg, another park a hundred miles away. By a decade later, elephants had killed about 49 rhinos, an extremely unusual behavior for elephants. Biologists came to suspect that young male elephants in the group were stuck in a rutting condition known as “musth,” during which testosterone levels dramatically increase. In a normal elephant herd, older male elephants will confront the younger ones and end the musth state, so officials decided to introduce six older males into Pilanesberg—and it worked. The rhino killings stopped. In the words of J.B. McKinnon:

Elephants are one of the few species in which the importance of older animals is coming to be acknowledged. Without them, the Pilanesberg orphans acted in a way so far outside of pachyderm norms that it seems fair to label it insane.

Clearly, elephants evolved in multi-age tribal groups. When a group of young elephants was isolated, violence erupted. When this particular “evolutionary mismatch” was eliminated by bringing in older male elephants, the “insanity” stopped.

Adolescence in the Environment of Evolutionary Adaptation

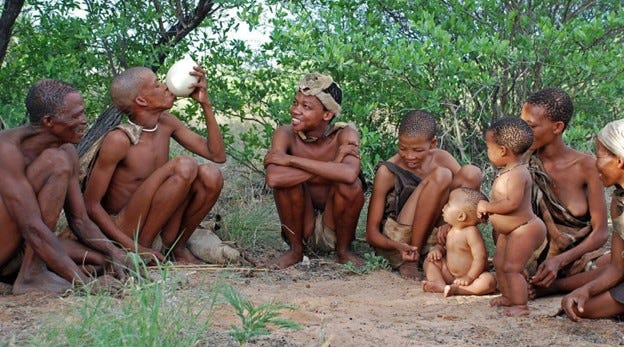

Human beings evolved over many millions of years in diverse physical environments. But with respect to social structure, until the dawn of agriculture and empire, it seems likely that almost all adolescents:

Lived in a small tribal community of a few dozen to a few hundred with few interactions with other tribal groups (even with regular tribal exchanges, the interactions were likely to be small compared to modern interactions).

Shared one language, one belief system, one set of norms, one morality, and more generally a social and cultural homogeneity that is unimaginable for us today.

Were immersed in a community with a full range of ages present, from child to elder.

Engaged from childhood in the work of the community, including hunting and gathering, with full adult responsibilities typically being assumed upon puberty.

Participated in mating and status competitions within their tribe or occasionally with nearby groups, most of which would have been similar.

Many contemporary adolescents in developed nations, by contrast:

Are often exposed to hundreds or thousands of diverse-age human beings directly and through electronic representations (both social media and entertainment media).

Are exposed to many languages, belief systems, norms, moralities, and social and cultural diversity.

Are largely isolated with a very narrow range of age peers through schooling.

Have little or no opportunities for meaningful work in their community and no adult responsibilities until 18 or even well into their 20s (or beyond).

Are competing for mates and status with hundreds or thousands directly and with many thousands via electronic representations (both social media and entertainment media).

Which of these differences between our environment of evolutionary adaptation and contemporary adolescence in developed nations result in which manifestations of mental illnesses? At present, we don’t know. But it would be surprising if these dramatic changes in the social and cultural environment did not have an impact.

Is Evolutionary Mismatch a Cause of Adolescent Mental Illness?

As nations become more prosperous, traditional public health concerns such as infant mortality and contagious diseases become less prevalent. At the same time, new public health concerns such as obesity, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes become more prevalent. Daniel E. Lieberman, a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard, explains the role of evolutionary mismatches in the increasing prevalence of such diseases:

“…most mismatch diseases occur when a common stimulus either increases or decreases beyond levels for which the body is adapted, or the stimulus is entirely novel and the body is not adapted at all.”

Lieberman’s book The Story of the Human Body: Evolution, Health, and Disease, is the definitive treatment of such mismatch diseases.

While the book largely focuses on physical diseases, Lieberman recognizes that the same mismatch principle is likely to be responsible for some mental illnesses:

“There is good reason to believe that modern environments contribute to a sizable percentage of mental illnesses, such as anxiety and depressive disorders.”

He adds ADHD, eating disorders, chronic insomnia, and OCD as mental illnesses whose modern prevalence is likely due in part to an evolutionary mismatch.

Journalist Johann Hari argues in Lost Connections that depression is caused by:

Disconnection from meaningful work

Disconnection from other people

Disconnection from meaningful values

Disconnection due to childhood trauma

Disconnection from status and respect

Disconnection from the natural world

Disconnection from a hopeful and secure future

While some of these disconnections are more robustly supported than others as causal factors in depression, all but the fourth and seventh one may be regarded as evolutionary mismatches. (It is not clear that we can generalize about childhood trauma in a world in which death was common, and there is no reason to believe that humans experienced a “hopeful and secure future” in the environment in which humans evolved.) But certainly “meaningful” work, connectedness to other people, and a profoundly coherent system of meaningful values was the norm. Also, most people would have experienced largely stable status and respect hierarchies, and of course they lived in the natural world.

Anomie and Mental Illness

To explore an additional direction, Liah Greenfeld is a Durkheimian sociologist who specifically attributes the modern epidemic of depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia to the burden of creating an autonomous identity in the modern world. She argues that in the past few centuries, modernity has gradually shifted away from traditional identities that were stable over generations to the modern notion of personal identity in which we each are expected to have the freedom and opportunity to pursue our own individual destiny.

In paleolithic cultures, human beings did not have the range, opportunity of choice, or responsibility to create their own identities that they have today. Greenfeld sees the Anglosphere, with its vast range of possibilities, as the culture most advanced with respect to anomie. In her account, the burden of creating an individual identity (as opposed to having one’s identity given to one by one’s family, clan, social role, etc.) began with the rise of national identity under Henry VIII. The notion of defining oneself has gradually spread from English elites throughout the Anglophone world, and to a lesser extent across all of modernity (i.e. “Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic” or “WEIRD” cultures).

This fact—the abundance of options in a society in which self-definition is the norm—explains why scholars such as Jean Twenge and Jon Haidt find that social media does the most harm in the Anglosphere. Separately, there is an entire literature showing that Latin American teens are more likely to exhibit suicidal behaviors the more engaged they are with American culture. This finding is aligned with Durkheim’s original finding that Protestants commit suicide at higher rates than Catholics, but suggesting a cultural factor rather than religion alone.

If the burden of self-definition, and the resulting anomie, is a causal factor in adolescent dysfunction, then might different forms of schooling be able to compensate for the individualism of Anglophone culture? Greenfeld believes that healthy identity formation within K12 may be a promising path forward.

Schooling and Mental Illness

The present paradigm of adolescent mental health takes the existing schooling system as a given. Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge have been emphasizing the rise of smartphones and the decline of free play as causal factors in the recent adolescent mental health crisis. Teens today spend the bulk of their time either in school or online. While addressing the digital addiction crisis and free play crisis, we should also be thinking about the evolutionary mismatch of learning environments. Here I will focus on suicide in order to sidestep controversies regarding changed diagnostic criteria. Most suicides are related to depression or other underlying mental disorders.

The evidence that teen suicides increase during the school year, especially on Mondays, is significant. Moreover, this is a seasonal pattern that stops at age 18.

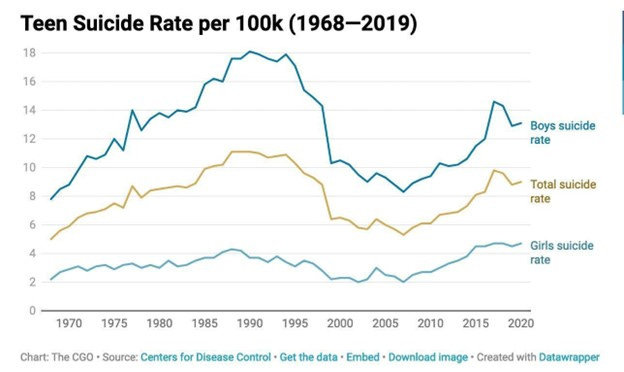

Teen suicide rates increased dramatically in the 20th century, declined in the 1990s (likely due to SSRIs) and have been increasing since the early 00s:

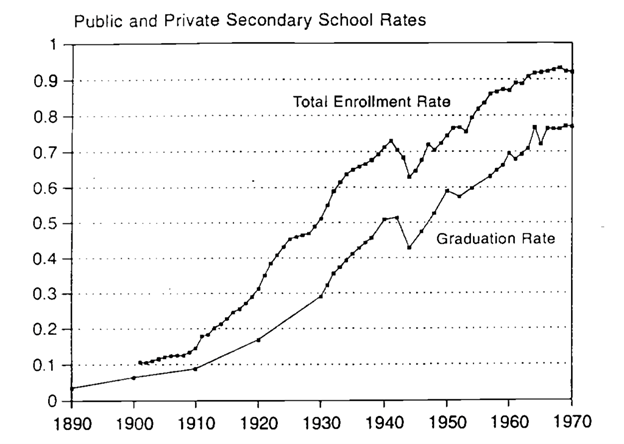

After rising to about 400% higher than in the 1950s, then back down to only about 200% higher in the late 90s and early 00s, they are once again approaching 350% higher than the 50s. Might the growth in teen suicides from 1950 to 1990 be a result of increased evolutionary mismatch during that period? This period corresponds to the rise of mass high school.

High School as Evolutionary Mismatch

We don’t know why, exactly, teen suicide increased 400% prior to the introduction of SSRIs. That said, the correlation with schooling is intriguing. For instance, the percentage of students completing high school increased dramatically after WWII:

A 2001 article on teen suicide shows the growth in teen suicides since the 50s (bottom line represents teens):

If we look at suicide rates age 15–19, white males increase from 3.7 per 100,000 in 1950 to 15.0 per 100,000 in 1980, more than 4 times. White females age 15–19 went from 1.9 per 100,000 in 1950 to 3.3 in 1980, a 170% increase. (White teen suicide rates were higher than black teen suicide rates until the late 20th century, perhaps due to the greater religiosity of blacks, with religion playing a protective role in many cultures).

For males, in particular, the growth in high school enrollment tracks the growth in teen suicides. When combined with the stark pattern of increased teen suicide during the school year, we should consider whether there is something problematic about the schooling environment for some teens.

Is there some proportion of adolescent males who are not thriving in the high school environment? Might these males have felt a sense of purpose in a work environment while also benefiting from being around adult males? Certainly, young male elephants do not do well when they are not raised among adult males. Is the salient evolutionary mismatch the lack of connection? The lack of purpose? The lack of adult males?

Lack of Connectedness and Purpose

Consider the lack of connectedness at school, sadly a common experience in the U.S. The Center for Disease Control cites “school connectedness” and “family connectedness” as the two strongest protective factors for a wide range of teen dysfunctions. With respect to school connectedness:

“School connectedness was found to be the strongest protective factor for both boys and girls to decrease substance use, school absenteeism, early sexual initiation, violence, and risk of unintentional injury (e.g., drinking and driving, not wearing seat belts). In this same study, school connectedness was second in importance, after family connectedness, as a protective factor against emotional distress, disordered eating, and suicidal ideation and attempts.”

From an evolutionary mismatch perspective, this is not the least bit surprising. If we evolved in small tribal groups, tightly connected with our peers, parents, and community more generally, then disconnection from them for extended periods of time is unnatural. As we saw above, in the case of young elephants, it turns them into murderous maniacs.

In a world in which young males were needed to hunt to contribute to the survival of the tribe, there would be neither anomie nor aimlessness.

In our world, Stanford psychologist William Damon has found that a sense of purpose is linked to adolescent well-being. He cites research that found that having a purpose in life reduces drug use, alcohol use, and antisocial behavior among young people. More generally, a purpose in life seems to improve physical health as well as psychological functioning.

Damon also cites evidence that most teens lack a sense of purpose:

“In a study that followed 7,000 American teenagers from eighth grade through high school, . . . ‘Most high school students . . . have high ambitions but no clear life plans for reaching them.’ They are, in the authors’ phrase, ‘motivated but directionless.’ As a consequence, they become increasingly frustrated, depressed, and alienated.”

Again, from an evolutionary perspective, teens would have been raised within a coherent meaning system with myths and behavioral expectations to which they were universally expected to adhere. In most environments, basic survival needs in a tribe which was united by and dedicated to survival, including honoring the hunters who were most successful, would have given a definitive sense of purpose to all.

It is not clear that the very language of “high ambitions but no clear life plans for reaching them” even makes sense outside of modern WEIRD societies. That language certainly doesn’t seem to reflect what we know about our environment of evolutionary adaptation.

Without providing any particular conclusive evidence connecting a particular phenomenon with a particular evolutionary mismatch, for now I simply want to open up the direction of evolutionary mismatch for adolescent dysfunction and mental illness for continued exploration and investigation.

Can Lack of Connection and Purpose Really Impact Mental Health?

Peper and Dahl summarized the rapidly growing domain of brain-behavior interaction in human puberty. Pubertal hormones may influence social and affective processing in the social context of adolescence. While in a healthy social environment these hormones lead to positive mental development, negative influences can cascade out of control:

However, these can also lead to negative trajectories such as substance abuse or depression. These negative trajectories may begin as small changes, but over time can lead to patterns of behavior that have cascading effects: brain-behavior interactions with spiraling impact across adolescence.” (bold emphasis added)

In the case of the Pilanesberg young elephants, a social situation (the lack of older males to stop their hormonal musth stage) led to behavior that was so exceptional that it was regarded as elephant insanity. Is it possible that what are initially relatively small evolutionary mismatches with respect to social environment could cascade and thus result in full blown mental health issues among human adolescents?

Social neuroscientist John Cacioppo has provided strong physiological support for evolutionary biologist E.O. Wilson’s simple statement, “People must belong to a tribe.” Cacioppo is explicit in connecting social neuroscience to mental health. His article concludes that the social factors and deficits are both causes and consequences of psychopathology:

“As understanding of the social brain advances, this knowledge can support understanding of mechanisms by which social factors and social deficits operate as causes and consequences of psychopathology.”

From the perspective of evolutionary psychiatry, the fact that social factors and deficits are sometimes the causes of psychopathology should not be the least bit surprising. We are now living in a social environment that is dramatically different from the environment of evolutionary adaptation.

Thus the result is that young people may experience distortions to their mental development during puberty due to a suboptimal social experience, and these distortions may cascade into more substantial issues. These mental distortions may then be exacerbated by subsequent social interactions. We need to take seriously the various ways in which the social environment of young people at school is profoundly unnatural.

Can We Educate Young People in Less Harmful Ways?

Can we create learning environments that more deeply satisfy adolescent needs for connection, community, meaning, and purpose? If we take the evolutionary mismatch hypothesis seriously, we clearly should be exploring how to do so.

Schools can and should be redesigned to be more aligned with our environment of evolutionary adaptation. There is neither need nor justification for schools to be as deeply mismatched as they are at present.

For instance, Montessori classrooms provide mixed aged classrooms in which students have much greater autonomy and agency and more opportunities for spontaneous movement. It is not quite playing hunter and gatherer games in the forest, but it is much farther in that direction than a traditional classroom. Importantly, mixed age classrooms allow for older students to serve as role models for younger ones rather than relying solely on adult control.

Separately, my focus is creating schools based on Socratic dialogue for secondary students (which have sometimes been adopted as a Montessori secondary model). It turns out that kids love to talk. This process itself creates greater connection, community, meaning, and purpose. By means of getting them to talk about philosophy, literature, science, etc., we can get kids engaged in intellectuality while allowing them the deeply social experience that adolescents crave—again reducing the evolutionary mismatch.

To take another example, secondary students love engaging in real world projects— making things that are valuable to other people, including novels, videos, software, music festivals, photography, etc. Montessori described this as "valorization," the need to be valued in the community by contributing something to the community. Again, in paleolithic cultures, at puberty young people would definitely be contributing to the community, often taking on adult or quasi-adult roles. The enforced passivity and infantilization of standard schooling is an extreme violation of human nature.

Add some outdoor time in nature and we are getting to high quality programs much more aligned with our nature—and I predict fewer "mental illnesses" the more we align K12 with the environment of evolutionary adaptation (while still robustly providing the skills needed to succeed in the 21st century).

If indeed our current model of schooling is an evolutionary mismatch that causes (or exacerbates) adolescent dysfunction and mental illness, then we should wholeheartedly be exploring alternative models for educating our children. While Haidt and Twenge’s campaign against social media is worth supporting, if the more fundamental underlying trend is the mismatch between schooling and adolescent well-being, then addressing social media alone might not halt the underlying negative trends that began in the 50s.

The elephant story reminds me of “Lord of the Flies”. Those boys had almost everything you advocate except adult influence.

Good to see a UATX author writing here. I support their (and your) mission wholeheartedly.

if I may mention the elephant in the room - ambition to achieve high status is surely part of the EEA for males but not obviously for females - what are the consequences of that? In any event, until recent decades there was an automaticity toward pairing and then mothering and fathering. That much hardly needed to be decided. Of course, now girls hardly know what they are for - with predicatable consequences. Best wishes to Michael in ameliorating at school changes originating elsewhere - I don't however think schooling is a source of the problems - it may fix some.