Coordination is not Cooperation – Coordination Part VI

Pickleball, sage grouses, and getting cranky about explanations.

Despite the fact that you and I are not friends—in fact, for this story we are bitter enemies—we have decided to go to watch a pick-up game of pickleball. I am, as it happens, quite tall, and you, as it happens, are quite short.1

Now, because I don’t like you, as soon as you pick somewhere to watch, I stand in front of you. Vexed, you shuffle one step to your right. As your bitter enemy, I dexterously match you. We do this song and dance for a while.

Let us now ask ourselves two questions:

Am I coordinating with you?

Am I cooperating with you?

The answer to the first question is unequivocally yes. Because I match you motion for motion, we are as coordinated as synchronized swimmers. If you took a god’s-eye view of the pickleball court, you would see two figures moving together as one (and have a great view of the game). The answer to the second question is just as unequivocally no. When I coordinate my movements with you, I am making you worse off, not better off. (I’m neither worse off nor better off, I suppose, no matter which position I’m at.) By no stretch of the imagination are we cooperating. Indeed, if anything, we are competing. If you could move in such a way that I couldn’t block your view, you would.

Alas, you can’t.

From this, we see that coordination is not the same as cooperation.

Two Stances

One of the surprisingly large number of ways in which I irritate my romantic partner is that I talk a great deal about explanation. A typical exchange will go something like this:

ME: I wonder why that bird is making that cheap-a-woooo sound.

HER: That sound is fairly typical of that species.2

ME: (Cocking my head, squinting a bit) Is that really an explanation of why it’s making that sound though?

HER: You are lucky I am a patient woman.

First, let’s be clear. I am for sure lucky she is a patient woman. Hashtag fair enough.

Second, yes, I am somewhat obsessed with explanations but, in my defense, I come by it honestly. As an academic psychologist studying human social behavior over the course of a quarter of a century, I had a front row seat to some of the worst explanations ever known to humankind.3 I am entitled to be cranky about it.

To be honest, I am not just generally cranky. Loyal readers might have noticed that I have been posting about coordination, in the service of talking about a theory of morality and moral judgment. It has come to my attention that despite what I felt to be a series of crystal clear and often very entertaining posts on this topic, some readers—I will not name names—still think my coordination account is a cooperation account.

This makes me specifically cranky and, in truth, simply will not do.

To remedy this, I am going to discuss cooperation and coordination from two different perspectives to illustrate the distinction between them. In this, I will be drawing on the work of the late philosopher Daniel Dennett,4 specifically his book entitled The Intentional Stance, which I recommend to every single person getting a PhD in philosophy or one of the social sciences. Everyone else should just ask ChatGPT to summarize what he was on about, which is what I did because I haven’t read the book since grad school.

The Intentional Stance

The main way that you and I explain people’s behavior is that we assume everyone has these invisible things called beliefs and desires. If I ask you to explain why Mary went into the kitchen, you’re going to refer to her desires—she wanted to eat something—and her beliefs—she thought that there was a bologna sandwich in the fridge. You would not refer to physical stuff. It would be bizarre if you said, well, the muscles in her legs contracted, causing her to move forward in the direction of the kitchen door. I mean, you wouldn’t exactly be wrong, but you also wouldn’t be helpful.

When, generally, I coordinate my movements with you, and we are seeking an explanation for why I am doing this, here are three things that I might intend when I do so.

I want you to be worse off; I intend to hurt you.

I want you to be better off; I intend to help you.

I do not care, even a little, whether I make you better off or worse off. I have no intentions toward you whatsoever.

We saw an example of (1) in the charming vignette that opened this post. This is a case in which I coordinate with you and my intention is to do harm.

There are a limitless number of examples. Suppose that you and I are on The Price is Right. It happens that I bid after you, and I always, irritatingly, bid one dollar less than you, so you will never win. (Because you have to be closest without going over. In this case, you’d have to hit the number right on the nose to win. Fat chance.) I am coordinating my bidding behavior with you. We’re in a competitive game: I can’t win if you do. I intend to beat you.5

Now, for a number of reasons, none of which6 I am going to guess at here, most of the time we think about coordinating with one another, we think of the second case. Lots of times when you and I coordinate—we are no longer bitter enemies in this scenario—we’re also cooperating, enjoying mutual gains. We go dancing, coordinating our movements. So fun! We arrive at the very same movie theater at the very same time. We watch a film together! While not all coordination is cooperative, most if not all of the cooperation I can think of requires coordination.7

In terms of the third case, think about any of the large number of interactions you have with strangers. You are trying to get to your flight on time, and there are a bunch of people on the right side of the passageway coming toward you. You shift your route to the left to reduce the time it will take you to get to your gate. If you are like me, you could not possibly care less that by doing so you are getting out of the way of the people coming the other way.

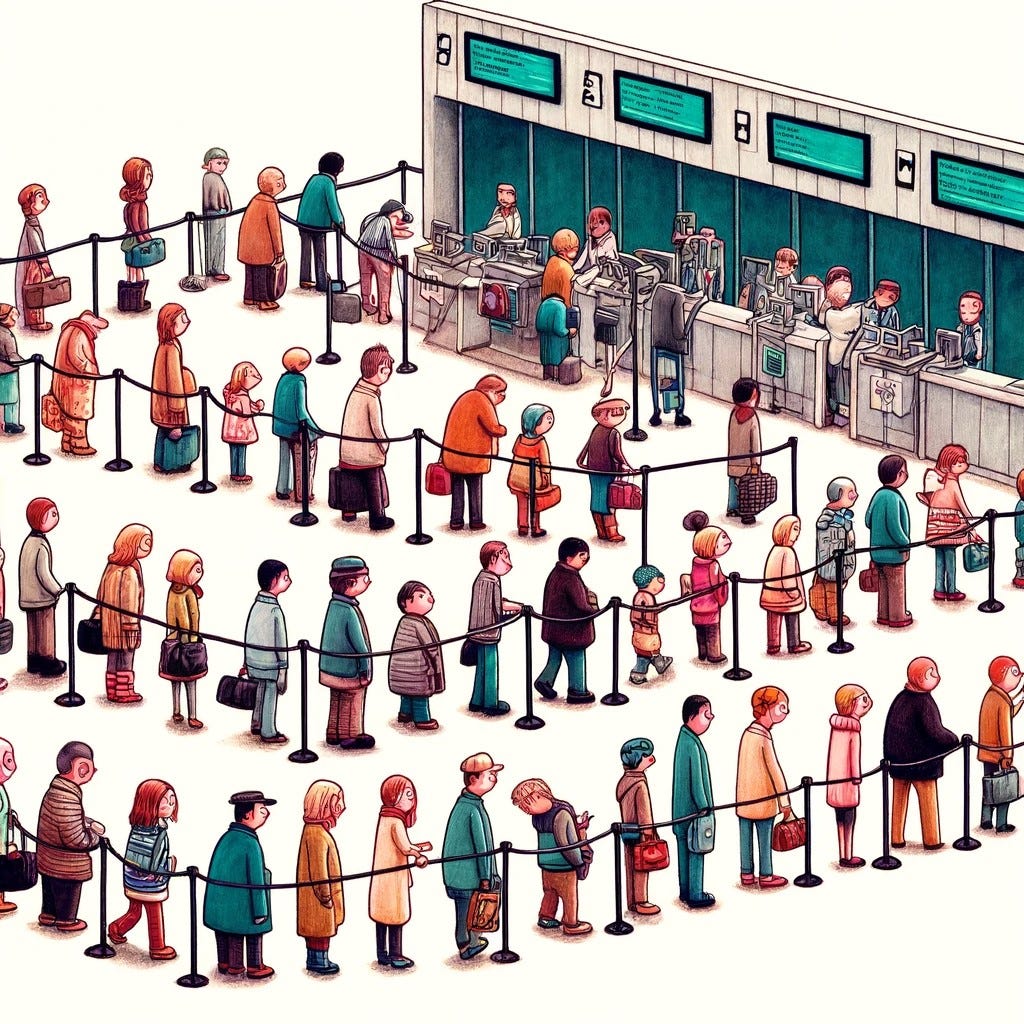

While we’re on the subject of travel, depending on how immigration at the airport is set up, you’ve probably noticed that the queues for each of the many officials checking your passport are roughly even. This coordination is simply because people choose the shortest line, which evens them out. No one cares about how this choice affects the next people in line, but pretty much anytime there are multiple lines, they are roughly even. It isn’t because people want the lines to be even: it’s because they always choose the shortest one.

Heck, you can coordinate with inanimate objects. One of the funnier scenes in a movie with plenty of funny scenes, Galaxy Quest, involves the characters timing a run so they don’t get squished by machines that are moving in a predictable rhythm. They have to coordinate their movements to pass safely. It should be abundantly clear that they are not coordinating with the gizmo to help the chompers. The chompers cannot be helped.

From all of this, it should be very clear that coordination is just emphatically (bold, all caps, italics) NOT the same as cooperation.

The Design Stance

Now, loyal readers of Living Fossils might have noticed that we make passing reference to evolution here and there. We are very interested in what various bits of the mind are for. We are focused on design. And design is another way to explain behavior, of both organisms and artifacts. Why does that second hand of a clock loop around in a circle every sixty seconds? Its function is to keep track of time. That explains its behavior. (See also the Antikythera mechanism. Once we understood its function—what it was designed for—its parts made sense.)

In the first post in the series on coordination, we visited a number of examples in which organisms were designed to coordinate with other organisms. Just as in the case of intentions, when an organism is designed to coordinate with other organisms, there are three possible explanations:

The trait is designed to make the other organism or organisms worse off.

The trait is designed to make the other organism or organisms better off.

The trait is designed to coordinate and whether other organisms are better or worse off is irrelevant to whether the trait is selected. If other organisms benefit or suffer, it is a side effect, not design.

Let’s consider the ferocious dance of the stag beetle. The males of this species use their large (for a beetle) mandibles to fight with other males, with each trying to drive off—or worse—the competition. Big horn sheep provide another vivid example. Related, consider the sage grouse. In this species, males gather together in a particular place—coordinating—but not for cooperative purposes. In this collection, called a lek, males display, trying to attract mates, to the detriment of the other males. These conflicts require the competitors to coordinate—they must be in the same place at the same time—though, as in the pickleball case, this coordination is competitive, not cooperative.

In contrast, some traits for coordinating are selected because of the benefits. In the first post on coordination, I discussed fireflies, who use signals to indicate to other fireflies which species they are. This allows matings to occur only within species. Coordinating in this way is good for the fireflies involved, and imposes no (meaningful) costs on other fireflies. Using signals to coordinate in this way is a relatively pure example of the second explanation. Cooperative hunting among related animals is another example of coordinating to cooperate.

Now, to end where we began, with our old friends the cicadas who come out at prime-numbered intervals. From the perspective of the individual cicada, emerging when a billion others emerge is good for it. This design is analogous to how you don’t care about the people behind you when you choose the shortest line at immigration. Why does the cicada emerge when others do? Is it designed to benefit other cicadas? No. It is designed to coordinate with other cicadas because by doing so, it maximizes its chances for survival and reproduction. The effect that it has on the other cicadas—a tiny positive one, in this case—is a side effect of that design.

From all of this, it should be very clear that coordination is emphatically (bold, all caps, italics) NOT the same as cooperation.

Coordination and Morality

Let’s return to our hiking tales.

As you will recall, in the key vignette, Duck (Crane’s friend) sided against Crane and with Anaconda and Beaver when Crane stole the mango.

Let’s look at this from the intentional and design stances.

From the intentional standpoint, why did Duck do this? After all, he’s Crane’s friend. The reason is that he wanted to avoid a fight with Anaconda and Beaver. His behavior was selfish, keeping himself out of a melee. As a side-effect of this choice, Anaconda and Beaver were better off because they didn’t have to fight either. But this was a side effect.

What about from the design perspective? The analysis is exactly the same. Why are humans designed to choose sides based on the actions of others—that is, why do humans have moral judgment? It’s because doing so puts them on the winning side of disputes, which is good for them. That’s the explanation for the design. Just as in the cicada case, it’s true that many others benefit, but that’s not why the side-taking psychology evolved. It’s another case like choosing the shortest line. It evolved because of the benefit to the individual, not because of the benefits to others. It is not a cooperative adaptation.

When humans coordinate with one another, siding against someone based on their action, the explanation is to do with the benefits to the self, just as in the cicada case. The design is not there because others are better off.

From all of this, it should be very clear that coordination is just emphatically (bold, all caps, italics) NOT the same as cooperation.

Right?

I am not quite tall. I have no idea how tall you are. I’m just setting up the hypothetical.

She is an avid bird watcher, you see, and knows a lot about birds.

I drafted this before his recent death. I’d love to say this post is an homage to him – he really was a great philosopher – but it’s just a coincidence.

A less whimsical example is pricing. Firms will sometimes price their goods and services just below that of the competition, for the same reason. See: neighboring gas stations.

Ok, one of which. See next footnote.

This might be why people conflate the two. It’s like thinking that all rectangles are squares.

I should add that the world that is the lek (an outcome of co--ordination trade-offs) becomes a substrate for selection itself as an umwelt, and then be a form of co-operation, i.e. co-ordination allows the possibility of co-operation to be selected for, indeed it may require co-ordination first. I.E. it is an outcome of co-ordination that grouse co-operate to compete from the POV of the chooser, why go shopping for Louis XIV antiques by heading off to an industrial zone of destroyed factories. Co-operation is an outcome not a cause (like religion/morality/polities/art) of the urge to should the self in a world.

ooh!!!

leks!