Hobbits - Part II

The Three Powers

This is the continuation of the series on the so-called Hobbits. These posts consider what would have happened if the little creatures found on Flores Island had lived to the present era. Please read the prior post for first part of this imagined history.1 This post visits three countries with three different approaches to these little creatures. The next (and last) post in this series will look at what the results of each approach were.

Politiken – 7 June 1953

A NEW CHARTER FOR THE KINGDOM—AND A NEW CHALLENGE FOR HUMANITY

By Niels Erik Lund, Copenhagen Correspondent (Translated from the Danish)

Yesterday’s jubilation on Christiansborg Square, as Their Majesties appeared on the balcony to mark the signing of Denmark’s new Constitution, will surely be remembered as one of the great moments of postwar renewal. As the crowds cheered and the bells pealed across the capital, an uneasy conversation hummed beneath the celebration: what, in the new order, is to be done about the småfolk?2

The question, once confined to scientific conferences and the provocative pages of weeklies, has taken on the unmistakable gravity of statecraft. In the fields of Jutland and on the wooded fringes of Zealand, the småfolk —descendants of the Flores discovery centuries ago—are now numerous enough to shape the habits of ordinary life. What was once a curiosity has become, in the words of one civil servant, “a fact of civilization.”

Since the first sighting near Silkeborg in 1949, reports have multiplied. At first, farmers spoke of stolen grain and vanished chickens, of small fires kindled in the shelterbelts and of tools gone missing from barns. Now there are entire hamlets, abandoned by their former inhabitants, where the earth shows the marks of their burrows. Veterinary authorities confirm at least two dozen cases of sheep or calves killed in the past year—attacks made not by wolves, which have long vanished from Denmark, but by bands of the hobbits hunting cooperatively, just as they did on their home island.

The government’s response, codified in the Act on the Protection of Lesser Humanoids of 1951, remains the most humane in Europe. It forbids the capture, trade, or intentional killing of the beings and grants them the status of protected sentient organisms, entitled to compassion under law. “Our duty,” said Prime Minister H. C. Hansen in the Folketing, “to protect what we do not yet understand.” To many Danes, weary of war and ideology, this measured tone has been a source of quiet pride. Left unsaid by many was the guilt worn by the Dutch about the citizens who were abandoned to their fates in places with names such as Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, and Sobibor.

Yet patience has its price. The Ministry of Agriculture reports that requests for compensation from farmers have risen tenfold since last year. Insurance underwriters, faced with mounting claims, now demand that shops and granaries install reinforced shutters and secure perimeters. Municipal councils debate new safety enclosures around playgrounds and public gardens. In Copenhagen, the city has begun to fit iron grilles beneath the wooden piers along the harbor to prevent burrowing. The result, some say, is the beginning of an architecture of anxiety: a Denmark of locks, barriers, and wire.

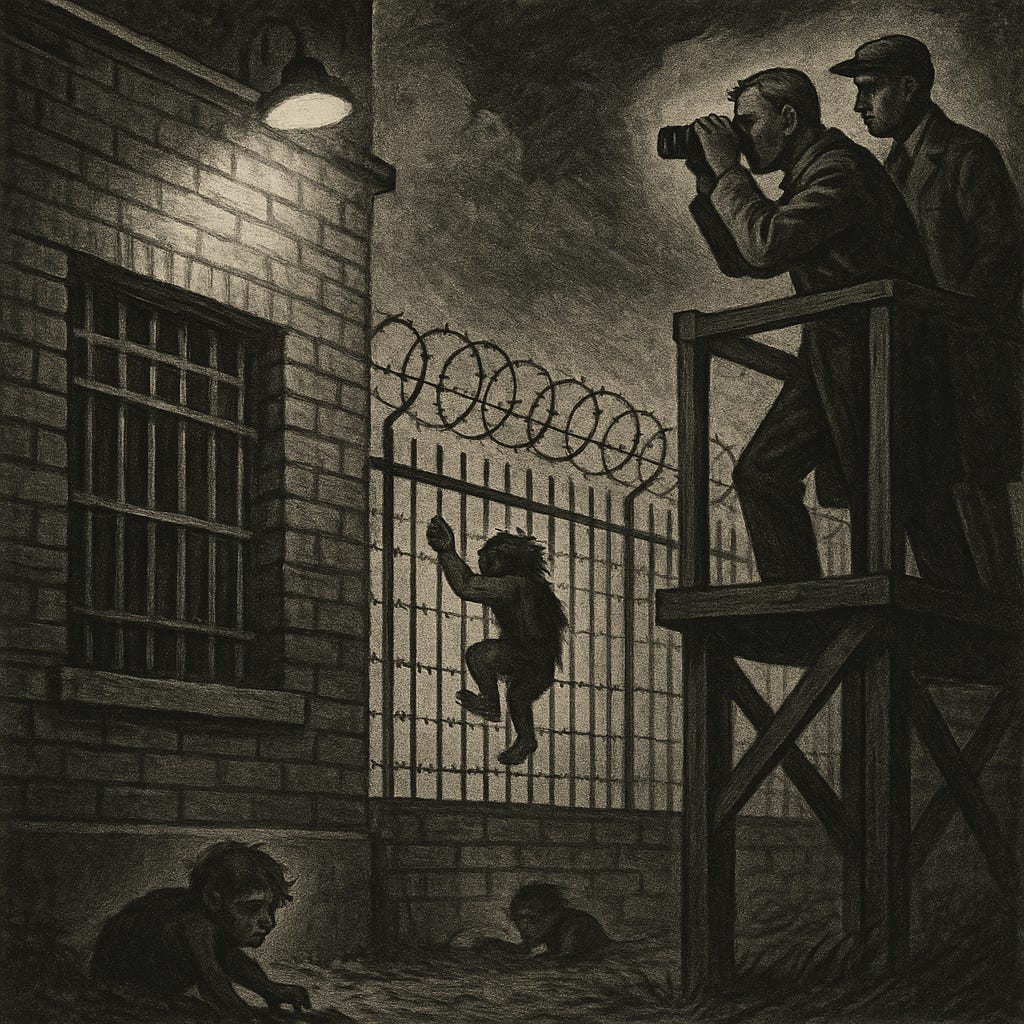

Officials insist that the creatures mean no deliberate harm. “They are opportunistic, not malicious,” explains Professor Nørgaard of Aarhus University, who has studied the species in the field. “They take what they can carry, much as our ancestors once did. The danger lies in their numbers and their appetite, not their intentions.” Even so, his team now conducts its research from elevated platforms after an assistant was bitten during a nighttime observation.

Public opinion remains divided. The Social Democrats defend the protective law as a moral test of civilization; the Conservatives call it naïve. In the countryside, tempers run hotter. A farmer from Viborg, interviewed on the radio last week, complained: “We are asked to show mercy to those who tear apart our lambs. If that is humanity, it is costly charity.” The Berlingske editorial page has warned that “sentimentality must not blind us to survival.”

Behind closed doors, ministers speak of “containment zones,” where the creatures might live without constant friction. The term kollektivbeskyttelse—collective protection—has appeared in internal memoranda, a characteristically Danish euphemism that, to some, recalls less gentle policies abroad. There is talk of electrified fences, though officials deny it publicly. “We shall not repeat the errors of history,” said one member of the Cabinet, “but neither shall we permit chaos in our fields.”

Outside the ministries, life adjusts. In markets, merchants display goods behind wire screens. Village councils organize nightly patrols armed so far with just whistles and torches. Schoolchildren are instructed not to leave food in their satchels, lest they tempt the hungry little ones. There have been no confirmed attacks on people—not yet, the police superintendent of Odense observed pointedly—but rumors circulate of a shepherd who mysteriously vanished near Esbjerg, his crook later found gnawed.

Thus the Constitution that grants equality of inheritance to Denmark’s daughters may also mark the first charter for a new kind of neighbor—one not born of Eve, yet sharing our air and soil. As one parliamentarian remarked during debate: “We may be the first nation in history to legislate friendship with another branch of mankind.”

Still, in taverns and the tramcars, a quieter sentiment prevails. “It begins with hens,” an old man muttered as he watched the fireworks over the palace last night, “and ends…” The man trailed of, seemingly unwilling to speak where it ends.

El Caribe – 12 March 1958

A CLEANER NATION, A SAFER FUTURE

By Rafael A. del Castillo, National Information Service (translated from Spanish)

Under the enlightened leadership of His Excellency Generalissimo Doctor Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina, Benefactor of the Nation and Father of the New Dominican Renaissance, our Republic once again demonstrates to the world that determination, discipline, and patriotism are the surest foundations of civilization.

In recent years, the tranquility and prosperity achieved through His Excellency’s guidance have faced a subtle but growing menace—the intrusion of the so-called Pequeños Hombres, or Little People, into the fertile valleys and hills of our beloved Quisqueya. First spotted along the western frontier, these creatures multiplied swiftly, preying upon livestock, raiding stores of maize and plantain, and spreading disorder among the rural communities that are the heart of our national soul. Reports from the provinces of Dajabón, Monte Cristi, and La Vega describe entire families of the creatures moving by night, taking food, tearing open henhouses, and frightening children.

What for some nations has been a source of confusion and timidity has, in the Dominican Republic, been met with clarity and strength. His Excellency has acted.

In the first months of this year, the government launched Operation Purificación Nacional, a comprehensive program of protection, sanitation, and defense designed to preserve the Dominican landscape for decent men and women. Conducted under the supervision of the Ministry of the Interior and the Armed Forces, the operation mobilized the National Police, the rural constabulary, and local civic brigades in a coordinated effort to expel the invaders. Where capture and relocation were possible, the creatures were sent by ship to destinations outside our national territory, especially to Denmark and other European nations inclined to accept this living cargo.

Unfortunately, in some few cases, the military’s attempt to capture the creatures to send them to more welcoming nations was met with unreasonable resistance and, sadly, sterner measures were, regrettably, required.3

Officials estimate that more than two thousand square kilometers of farmland have now been cleared, restoring safety and confidence to the countryside. “Once again,” declared Minister of Agriculture Don Carlos Rodríguez Alfonseca, “the Dominican peasant may sleep without fear that his hens will vanish or his crops be despoiled.”

Foreign observers who decry firmness in the face of danger would do well to recall the example of nations that waited too long. His Excellency has taught us that order is the mother of progress. As he said last week in his address to the National Assembly, “We are not a jungle people. We are a Christian nation. And a Christian nation must guard both its body and its soul against corruption.”

Following the success of Operation Purificación, the Law for the Preservation of Public Health and Tranquility was enacted on March 1st. This law forbids the entry, harboring, or trade of the so-called Little People within Dominican borders. Violators face imprisonment and confiscation of property. The Army has constructed fortified observation posts along the western frontier—our Muro de Dignidad—to ensure that no more of these dangerous beings pass into our territory.

In addition, the newly formed Commission for Biological Order, chaired by the naturalist Dr. Manuel de Jesús Troncoso, has issued guidelines for the humane disposal of infected remains and for the sterilization of areas where the creatures have dwelt. “Cleanliness is patriotism,” reads the Commission’s motto, echoing His Excellency’s well-known maxim that order begins in the home and extends to the nation.

Public celebrations throughout the provinces attest to the people’s gratitude. In Santiago, schoolchildren paraded with banners reading “Trujillo Nos Protege de la Amenaza Inferior.” In La Romana, the Women’s Civic League distributed thousands of pamphlets praising the President for defending “the dignity of Dominican motherhood from nocturnal terrors.” At the Military Academy, cadets performed maneuvers in honor of the success of the campaign, which General Ramfis Trujillo described as “a model of national coordination between soldier, scientist, and citizen.”

While some foreign newspapers have sought to misrepresent our policy as cruel or excessive, such criticism, often issued from capitals that cannot control their own vermin, is of no concern to us. The Dominican Republic stands as a beacon of stability in the Caribbean: a land without beggars, without anarchy, without fear. The same firmness that restored order in 1937 and that has built roads, schools, and factories from sea to mountain has once again preserved the purity of our nation.

Indeed, as President Trujillo reminded delegates of the Organization of American States in his message last month, “Humanity is tested not by its indulgence toward the savage, but by its fidelity to the civilized.”

With the Little Men now removed from our soil, new opportunities arise for agricultural modernization. The Ministry of Public Works has announced plans to drain the reclaimed lowlands near Mao and to establish a model cooperative under the direction of the Dominican Party. In this way, even the brief intrusion of chaos will serve the greater design of progress and prosperity.

At sunset yesterday, in a ceremony at the Plaza de la Beneficencia, the National Symphony performed Gloria al Jefe while school choirs sang of victory and renewal. Citizens waved flags embroidered with the national motto—Dios, Patria, y Libertad—and portraits of His Excellency adorned the balconies. The air was clear, the streets swept, and not a whisper of the nocturnal mischief that had so long disturbed our peace.

As the fireworks burst above the Ozama River, a radio announcer’s voice carried the simple truth that every Dominican knows in his heart: “Where others hesitate, we act. Where others debate, we build. Under the protection of Trujillo, the nation sleeps soundly. The darkness has been driven back.”

The Asahi Shimbun – 16 November 1962

SHIKOKU PLAN ANNOUNCED: A HUMANE SOLUTION TO A DIFFICULT PROBLEM

By Kenji Matsuda, Political Correspondent (Translated from the Japanese)

At a press conference yesterday in Tokyo, the Cabinet announced what officials are calling the most comprehensive domestic policy since the postwar reconstruction: the Special Administrative Plan for Shikoku. Under this long-term initiative, the government will gradually relocate all human residents of the island of Shikoku to the main islands of Honshu and Kyushu, while preparing the evacuated territory for exclusive occupation by the so-called Kobito-shu—the Little People—whose numbers in the Japanese archipelago have been rising sharply.

Chief Cabinet Secretary Takahashi Haruo described the measure as “a decisive step toward restoring harmony between mankind and nature.” He emphasized that the plan, to unfold over the coming decade, “will safeguard both our citizens and these diminutive beings, who, though not of our race, share the protection of our civilization.”

A Growing Presence

Since the first confirmed landings on the southern islands of the Nansei chain in the 17th century, the creatures have spread steadily northward, assisted by fishing vessels, storms, and perhaps—according to a 1959 Fisheries Agency report—by stowing away in cargo bound for Osaka and Kobe. The warm, wooded hills of Shikoku have proven singularly attractive to the inhabitants of Flores. In the intervening years, thousands of sightings have been verified, and damage to crops, fisheries, and livestock has multiplied.

The creatures’ small stature and nocturnal habits make accurate counts impossible, but officials of the Home Ministry estimate that as many as 250,000 now reside in Japan, the vast majority concentrated in the southern parts of the country, especially Shikoku. “It is a matter of time before they outnumber the human inhabitants of some rural districts,” said Dr. Mori Kazuo, of the National Institute for Population Research.

Japan’s challenge, unlike that faced by other nations, lies not only in numbers but in trust. In a society accustomed to unlocked doors, unattended bicycles, and the unsupervised journey of schoolchildren, the arrival of the Kobito-shu has struck at the heart of daily life. In Kagawa Prefecture, in a break with centuries of tradition, merchants keep their shutters closed even by day. Housewives speak of small hands reaching through the wooden slats to snatch rice balls cooling on the sill. The postal union reports that letter carriers have been bitten while making deliveries in remote areas.

The incidents have not been confined to theft. Authorities in Tokushima and Kochi acknowledge at least fourteen cases in which children walking alone to school were attacked by bands of the creatures, apparently seeking food or items to trade. No children were killed, though one remains hospitalized with severe lacerations. “It is difficult,” remarked the police commissioner of Ehime, “to maintain order among beings that do not recognize law, ownership, or rights.”

The Government’s Two-Pronged Approach

The Shikoku Plan, developed under the direction of Prime Minister Ikeda Hayato, rests on two pillars. First, a Resettlement Program will provide financial assistance, housing, and employment incentives for families who voluntarily relocate to other prefectures. Industrial cities such as Okayama and Hiroshima have already pledged to absorb displaced populations. The government promises that “no Japanese will suffer hardship or loss of livelihood as a result of this transition.”

The second prong is the gradual Transfer of Stewardship—the term used in official documents—for the island itself. Over a projected period of fifteen years, Shikoku will be “restored to its natural condition,” with infrastructure dismantled, roads unpaved, and agricultural lands left fallow. Once human habitation ceases, the Kobito-shu will, according to the Ministry of Science, be “allowed to occupy the area freely under observation.”

“The plan recognizes biological reality,” explained Dr. Saito Jun, director of the National Zoological Council. “These beings thrive where human presence is minimal. By granting them an island of their own, we prevent conflict while preserving our social order.” He added that the program would offer “unique research opportunities” for anthropology and ethology.

Dr. Jun also emphasized that the Kobito-shu will not be left to their own devices. Ports will be left intact and walled, allowing supplies to be shipped in to eliminate the need for competition among the locals for food. When asked what measures would be in place for population control, he indicated that the matter was currently being debated.

Public Reaction

Reaction among the public has been cautious but largely supportive. Editorials in both Yomiuri and Mainichi praised the government’s foresight, noting that “firm action today will prevent tragedy tomorrow.” The Buddhist Association of Japan expressed guarded approval, stating that “compassion sometimes requires separation.” The Socialist Party voiced doubts, arguing that “segregation, once begun, usually portends much worse.” Professor Ishida Hiroshi, a sociologist at Tokyo University, observed in a recent symposium: “Our society is built on trust, and trust cannot be rebuilt behind locks. The Kobito have shown us that our strength is also our weakness.”

Still, unease spreads quietly. In the village of Aki, an old man told this reporter: “We used to sleep with our doors open. Now we keep them locked and light candles all night. If they are to have Shikoku, let them take it. We have already lost it.”

Last week, at a ceremony marking the start of the Resettlement Program in Takamatsu, schoolchildren sang “Umi no Koe”—The Voice of the Sea—before a row of dignitaries. Prime Minister Ikeda, a color-coded map of Japan behind him, spoke briefly: “The Japanese people are a family. We have endured earthquakes, war, and hunger. We shall endure this, too. Let the little ones have their island. We will build our future elsewhere.”

The applause was polite, the sea wind cold. Behind the podium, the map of Shikoku had already been tinted green.

As in the last installment in this series, I have leaned on ChatGPT for prose and help with the history.

Some have started to refer to these as “hobbits,” drawing on the book by JRR Tolkein, who seems to have used the creatures as inspiration for the halflings in his 1937 fantasy novel.

The International Federation for Human Rights would subsequently claim that more than 50,000 little people were killed during this operation. The true number will never be known.

This thought experiment brilliantly exposes how diferent political systems respond to genuinely novel ethical dilemmas. Denmark's cautious humanism versus Trujillo's brutal efficency versus Japan's pragmatic segregation each reflects their deeper cultural values. The way you framed each through period newspaper writing is really efectve. Makes me wonder if our current debates about AI rights will follow similar patterns across societies.