Part I (Rob)

You make your living as a hunter.

One day, you head out from basecamp, hiking a fur piece toward one of the patches you know that animals frequent. Maybe you head down toward the watering hole. You heard there were antelope there a few days ago. Maybe you make for the river. Otters are nesting there this time of year. Or maybe you hit the open savannah. It’s migration season for the buffalo.

Today, you decide to hit the watering hole. A seasoned hunter, you know what to look for and how to be patient. Your preferred technique is an ambush: find or make a blind, strike before the prey sees you or catches your scent.

Unfortunately, all the tracks and droppings here are old. No one has been around here for a few days. It’s too late to head to the river. Best to make camp.

Now, while there aren’t any prey around, there are other predators that pass these parts, including the most dangerous predator of all, the people from the village on the other side of the river who occasionally ford across it when it is low, as it is now.

Starting with your blind, you turn it into a little lean-to with some more branches and fronds. It’s not big and it’s not elegant, but it’ll protect you, more or less, from the elements and mask your scent, at least a little.

Before you go to sleep, you work through your carefully rehearsed ritual. Your supplies are bound against the wall of the structure, out of the way. To the left of your little sleeping pile—always to the left—is your throwing spear, just within reach, leaning against the wall at an angle just so. You can roll over and have it in your hand in moments. If you hear something that you might be able to take with a good throw, you’ll be ready. To the right of your little sleeping pile is your favorite dagger. It’s right next to you, in reach as you are sleeping. If someone—or something—approaches stealthily and you need a close-combat weapon, you know where it is so that you can put it to good effect. The rest of the structure is bare. Nothing on the floor, nothing protruding into the room. Knowing that everything is exactly where it should be—almost like tools tucked neatly into their silhouettes on a peg-board—you are able to fall into a gentle sleep.

The next morning you awake, having slept soundly. Nothing went bump in the night, though you were ready if it did. It’s possible that you’ll revisit this little structure on your way back to basecamp, but you probably won’t. You leave the structure up but it does not occur to you to pick up the remains of your dinner or scrub the floor. What would be the point? You head out, setting a course for the river.

Part II (Rob)

You make your living as a gatherer.

Most days you head out from your small but perfectly serviceable hut to find and bring back the bounty that nature is providing today. Right now, the tubers that grow not far from the area cleared for the village are ripe. Just as you did yesterday, and probably will do tomorrow, you head out to the jungle with your digging stick and large sack.

The work is time consuming, requiring persistence, a little practice, and a song in your heart to keep the boredom at bay. Today you dig up three good-sized tubers. In addition, the blackberries nearby have started to ripen, and the early ones are ready to be picked. You return to the hut with the fruits, as it were, of your labor.

After preparing your meal—the tubers need to be peeled, cleaned, and cooked—you diligently remove all the leftovers from the processing from the hut. Leaving bits of food around might attract vermin and, if left for too long, will rot, inviting an unpleasant odor and, of course, the risk of germs in the house.1 You use your broom, such as it is, to sweep the floor until the last mote of organic matter has been exiled. For good measure, you clean the broom handle itself. Because you will be sleeping in the same place tomorrow as you did today, you ensure that all is spotless.

You find a place where you can tuck the broom, leaning it against one of the walls. The place is small and you can take your time when you need it tomorrow, so you just sort of put it anywhere you can find a spot. The digging stick gets a similar treatment. Today you left it on the little table by the door. You shouldn’t be able to miss it when you head out tomorrow.

Before you go to sleep, you carefully wash your hands and face. You bar the door with the latch your partner made before leaving for the hunt. You sleep soundly knowing that you’re safe in the village. Predators don’t come around, given how many people there are, and there hasn’t been a raid in a long time.

You awake to a spotless house. When you’re ready to leave, you momentarily forget where you left the digging stick but you eventually look on the table by the door. You lost a moment or two, but no matter. The day is plenty long.

Part III (Josh)

What would happen if you put the person from Part I of this story in a small apartment with the person from Part II of this story? Do you think they might have different preferences about how things in the apartment were arranged? Would they assign different priorities to keeping the place tidy, with everything in its place, as opposed to keeping the place clean, scrubbed and polished?

Might these different preferences lead to a certain amount of conflict?

Good questions…

In my practice—and, come to think of it, my life—I’ve noticed the outsized impact of household conflicts on relationships’ health and happiness. Couples are supposed to do the bulk of their fighting over big-ticket items such as money, sex, the future (e.g., whether to have children), values (e.g., how to raise children), and in-laws (e.g., wtf is up with your mom?) But household conflicts, such as the proper way to load the dishwasher, represent a much larger share of overall conflict than most people would guess.

Let’s throw this out to readers. What percentage of your arguments with your partner are sparked by a disagreement in how your living space is organized? For example, whether the bed should be made every day, how often the sheets should be cleaned, where the sponge should go after the dishes are done, when and how the dishes should be done, how often the vacuum should be run, when the Christmas tree should go up and down, and so on.

We’ll report the results next week, but our prediction is that household conflicts are more common than most people think.

They are at least common enough, to my mind, that I think couples should live in a duplex. Not side-to-side—that’s weird—but top-to-bottom. Why? Because there’s something nice about sharing a roof together, as well as obvious conveniences (especially while raising a kid), but there are also underrecognized benefits to each person having their own space to manage how they wish. Of course, if you aren’t swimming in money, you could simply divide the house into separate domains, as my wife and I have done. If my wife crosses over into the backyard, for example, I’m entirely within my rights to Supersoak her.

Why do men and women have different preferences in how their living space is arranged? As Rob’s opening parts suggest, because humans have a long history of division of labor by gender. By and large, men have hunted and women have gathered.2 Conflicts of household management might, on average, congregate around the differences wrought by these traditional occupations.

As a brief aside, a funny observation of this division of labor is that, contrary to what the reader might at first imagine, some anthropologists have argued that in some cultures, women gather more calories than men hunt. So why don’t men gather more? Eric Smith and colleagues suggested what Rob and I like to think of as the “Every Dog Has Its Day” hypothesis. If a man comes back with a sack of berries, he has enough to feed himself and his family for a day. That’s nice—but not as nice as lugging a giraffe back to camp, at which point he’s the talk of the town. Now he can feed his family and slang some meat elsewhere, perhaps picking up a little sexual action for his troubles. So, basically, men might prefer hunting because they’d rather be a hero for one day of the month than a regular Joe every day. Good thing there are women to, you know, keep everything else running.

These differences in labor roles over time led to cognitive differences between the sexes. For example, women are better at object location memory (where did we put the spare batteries?) while men are better at orienting (which direction did we come from?). This was uncannily reproduced between my wife and me the other day at Reading Terminal. Even though I went in ahead of her, she located not only the store we were trying to find but also the item we were trying to buy faster. When it came time to leave, though, I knew the direction of the door through which we had entered.

Rob and I are suggesting these cognitive differences extend to the harder-to-study realm of preferences for household arrangement. A simple way to summarize the difference is that women prefer things to be clean—as in, no germs—whereas men prefer things to be tidy—as in, everything has its place.3 Ultimately this is for the reasons Rob alluded to above: women, who have a smaller, more predictable sphere of travel, must manage it more sanitarily, while men must be ready to go at a moment’s notice, whether to kill, defend, or move on, pathogens be damned.

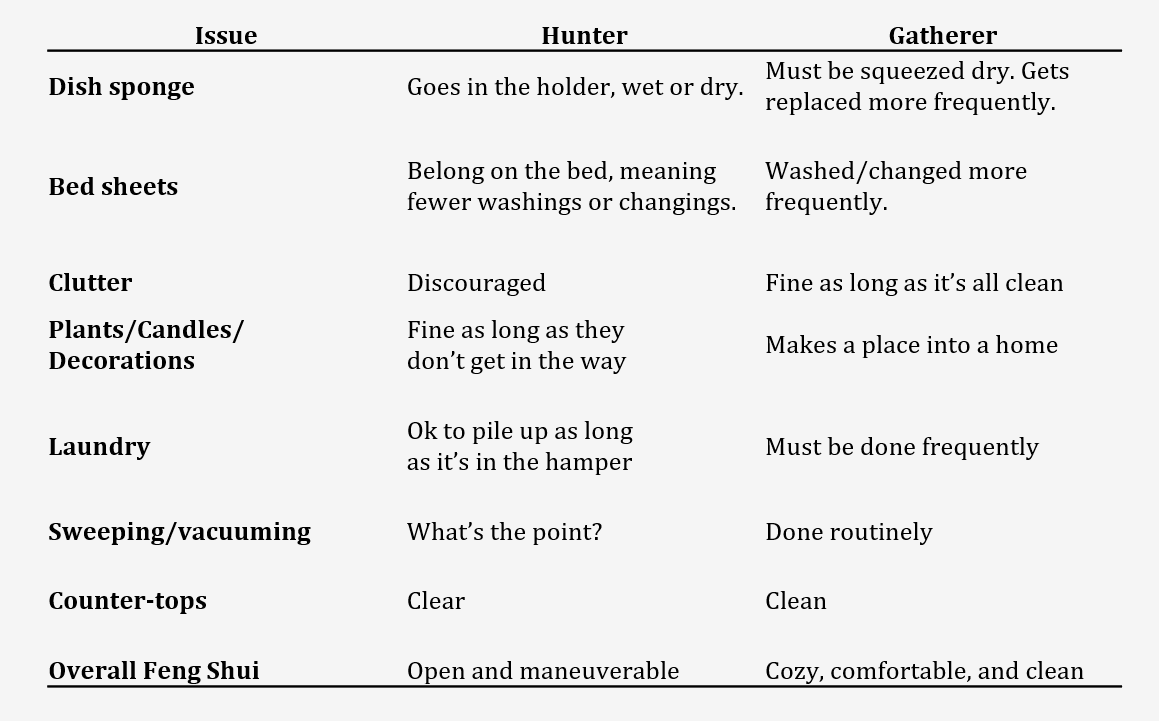

On this basis, we expect disagreements on average to break this way:

Part IV (Rob & Josh)

There are a few important exceptions, caveats, and implications of what we’ve suggested above. The main takeaway, of course, is that you should definitely get a duplex if you can.

Exceptions

You might have had the nagging thought throughout this article: what about same-sex couples? On the basis of this argument, we’d predict that they would have less household conflict because their preferences would be more aligned, all else being equal.

Not all else is equal, though. Despite having stone-aged minds, we live in a modern world, which can make it difficult if not impossible to recognize evolved preferences in action. For example, the majority of material things couples fight over, from dishwashers to sheets to TV remotes, did not exist for most of human history. However, it might still be possible to see our primitive desires shining through in how we interact with these novel technologies.

Caveats

The main caveat with this kind of research, and these kind of speculations, is that they are about averages. Almost every reader will be able to identify instances in which they or their partner breaks the mold (no pun intended). Likewise, our attempt is to express what is, not what should be. Certainly, it’d be much better if both sexes preferred to arrange space in the same way.

It's also important to note the mediating role of culture. Among other things, culture tells men and women how they ought to behave. If a woman lived in a culture that prioritized her ability to hunt, then this priority would interact with the potential evolved preferences discussed here. The result would likely be some sort of compromise that depended on a number of other factors.

Additionally, the question of how accurately the groups that anthropologists study represent the typical ancient ancestor remains open. For instance, contemporary or surviving hunter-gatherers often inhabit regions so barren that agricultural empires never sought to conquer them. What implications does this have for the observation that men generally hunt more than women? This could either enhance or diminish its significance. In areas of scarcity, there might be an ‘all hands on deck’ approach, leading to more women participating in hunting than usual. Conversely, if game is scarce, only the most skilled hunters might attempt it. If these top hunters are predominantly men, it suggests that women may have hunted much more frequently in resource-rich areas before the advent of agriculture.

Implications

What can those who cohabitate with someone take away from this article? That much of the time, the trivial-seeming disagreements that spark larger fights—how many times have I told you to return the sponge to its holder?!—might have an ancient basis. Or primitive, I guess we could say, to capture both how old they are and how dumb they these arguments seem in retrospect.

That said, it might help to acknowledge the foundations of these preferences. No single approach is superior; each might simply reflect a different evolved priority. This perspective should also suggest compromise as a more fruitful remedy than logic or argument. For example, Josh and his wife used to argue a lot just before bedtime. Possibly because he descended from hunting males, possibly for another reason, Josh preferred hitting the hay as soon as he was ready. He’d brush his teeth, get in bed, and be asleep within ten minutes. But ten minutes was barely enough for his wife to begin her night-time ritual. So Josh would often sit in bed, growing impatient with how long he had to wait.

The solution was for Josh to do the dishes (left from dinner) while his wife got ready for bed. When she was nearly there, she’d call out, and they’d go to bed together. How cool is that?

In his practice, Josh finds that couples are more restrained by cultural assumptions and norms than individuals. An individual client is much more likely to identify some cultural norm as not working for them and give it up. But for whatever reason, couples are more constrained. Couples and couples’ therapists should be more aggressive in searching for a compromise that works for both people.

You know, like a duplex.

WORKS CITED / FURTHER READING

Bird, R. B., & Power, E. A. (2015). Prosocial signaling and cooperation among Martu hunters. Evolution and Human Behavior, 36(5), 389-397.

Bliege Bird, R., Smith, E., & Bird, D. W. (2001). The hunting handicap: costly signaling in human foraging strategies. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 50, 9-19.

Hawkes, K., & Bliege Bird, R. (2002). Showing off, handicap signaling, and the evolution of men's work. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews: Issues, News, and Reviews, 11(2), 58-67.

Nazareth, A., Huang, X., Voyer, D., & Newcombe, N. (2019). A meta-analysis of sex differences in human navigation skills. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 26, 1503-1528.

Silverman, I. W., Choi, J., & Peters, M. (2007). Gender differences in object location memory: A meta-analysis. Memory & Cognition, 35(8), 1933-1946.

Smith, E. A., & Bird, R. L. B. (2000). Turtle hunting and tombstone opening: Public generosity as costly signaling. Evolution and human behavior, 21(4), 245-261.

Not that you know about germs, of course.

This doesn’t mean that women didn’t hunt, nor that men didn’t gather. We’re just talking averages. This piece does a nice job of summarizing the situation.

Men don’t like clutter, either, because that generally means that things aren’t where they belong.

Spot on.

I’m glad you guys are writing these, and I enjoy seeing what you come up with every installment. This was a fun approach to tackle a big topic.