Here’s how the leopard got his spots.

Once upon a time, leopard and his friend, the Ethiopian, had plain, sandy-colored coats that blended well with the open, sandy landscape. However, one day they decided to move into the dense, dappled forest. The leopard and the Ethiopian struggled to catch food because they were easy to see in their new surroundings. Standing out made sneaking up on prey difficult.

To solve this problem, the Ethiopian changed his skin color to a deep black to blend into the dark forest shadows. Seeing this, the leopard suggested that the Ethiopian use his newly blackened fingers to paint spots on his coat. The Ethiopian did so, and the leopard found he could blend into the dappled light of the forest, making him a more effective hunter.

And that is how the leopard got his spots according to Rudyard Kipling's “Just So Stories for Little Children,” a delightful collection of tales that tell origin stories of various features of the animal kingdom. First published in 1902, these stories were written by Kipling for his daughter, Josephine.

When I talked to ChatGPT about this particular story, it said that it “whimsically explains why leopards have spots, attributing it to their need to camouflage in the patchy light of their environment.” It added that “each [Just-So] story is a fantastical fable that provides a fictional explanation for why certain animals look or behave the way they do today.”

Note that ChatGPT claims that Kipling’s story explains how the leopard got its spots, and that the stories in general provide explanations for anatomy or behavior.

I point this out in part because of an excellent recent interview between Lionel Page and Steve Stewart-Williams, published on December 18th on Page’s Substack, Optimally Irrational.1

In the interview, Page, after asking Stewart-Williams to define evolutionary psychology, begins with the following question:

Evolutionary psychology is often criticised for not being scientific. It’s accused of producing ex post “just-so stories” that rationalise conveniently some observed behaviour with hypothetical scenarios.2

This caught my attention because this debate—is the field of evolutionary psychology composed of this sort of storytelling?—has been going on for decades.

I somehow find this both stunning and completely unsurprising.

Back in the 90s when I was a graduate student, I came across this critique with some frequency. I found it puzzling at the time because in graduate school, those of us who worked from an evolutionary perspective were approaching discovery in the same ways that other people studying human behavior did, with one exception: unlike our friends in social psychology, our approach was grounded in a well-established theory that had withstood falsification for more than a century, evolution by natural selection. We developed hypotheses, tested them, analyzed data with the statistical tools we had at the time, and so forth. It was hard to understand3 why starting with an established theory somehow made our science less scienc-y, rather than more.

I wasn’t really just puzzled. I was irritated. There was no shortage of derision aimed at my field—and, yes, me—along the lines of what Page is getting at.

In one case, I was so irritated I did something about it, a something that had essentially no effect whatsoever. When I was a post-doc, I wrote a review of a book edited by Steven and Hilary Rose, with the subtitle Arguments Against Evolutionary Psychology. I published the review, working through the more egregious errors of fact and logic in the book, including the remark by the singular Stephen J. Gould, who wrote that “the key strategy proposed by evolutionary psychologists for identifying adaptation is untestable and therefore unscientific.”

If ever there were someone tilting at windmills, it was me.

Why do critics of evolutionary psychology continue to level this claim, which we have addressed ad infinitum. I would love to say, diplomatically, that it’s because some of our explanations haven’t been well written or some critics are coming from a different perspective. Something nice like that. But that’s not it. It’s because many of these critics don’t understand the philosophy that underlies science, especially when it comes to explanations.

Now, don’t get me wrong. Explanation is a tricky business. It can get confusing.

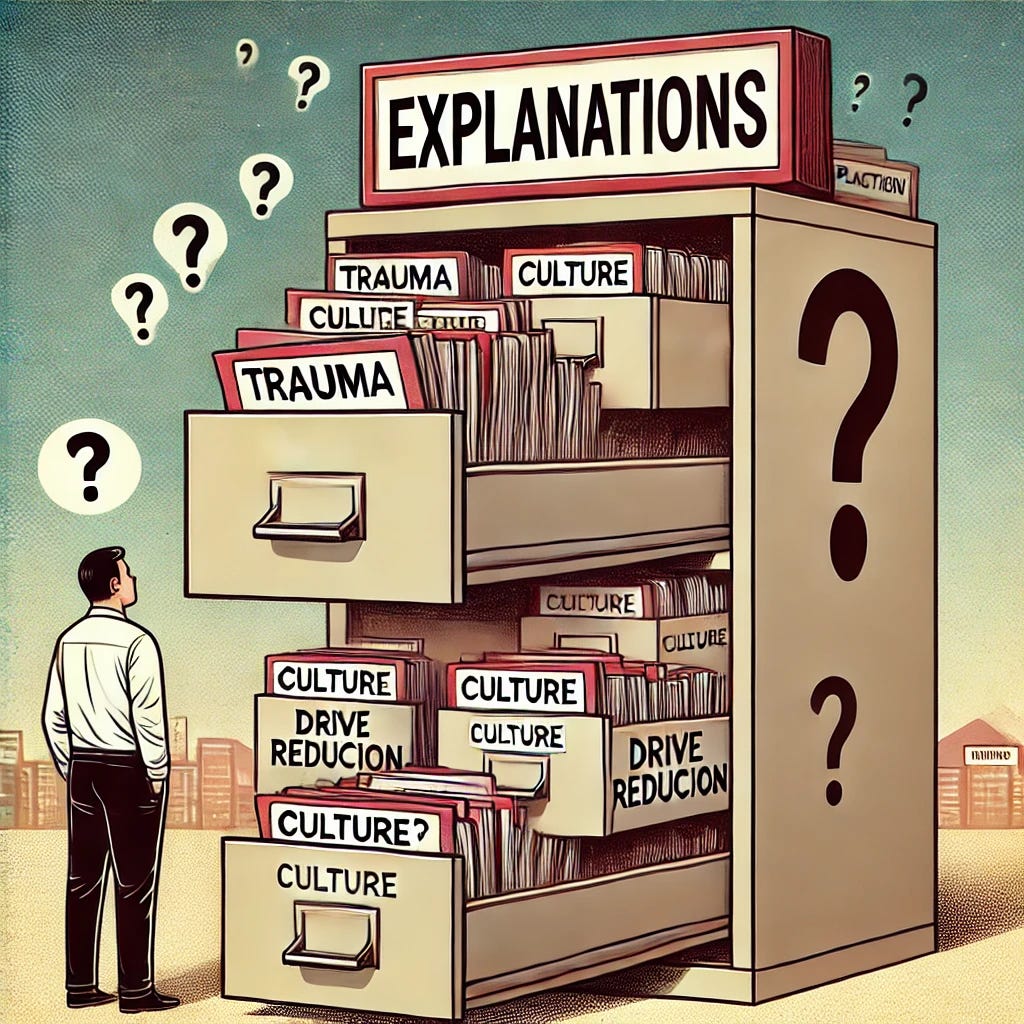

According to some people, Just-So stories are the opposite of explanations. If something is a story about this or that, some say, then it is not an explanation for it. To call something a Just-So story is, as the kids say, a diss.

But, wait a tick. ChatGPT—a disinterested third party if there ever were one—says that these stories are explanations.

How the Psychologist Got Confused

Many years ago, I was having dinner with a collection of Very Smart People, the sort that get invited to scientific gatherings where academics try to impress one another and eat free meals.

It was at one of these free meals—I think it was a schnitzel place?— that I asked the gathered worthies if people eat faster when they are hungrier. I myself certainly do this, but I was loath to generalize from my very small sample size of little ol’ me.

The table agreed that this was, indeed, the case, and I wondered aloud why. The senior Very Smart Person, to whom everyone’s gaze had turned, squinted his eyes slightly and, after a dramatic pause, said, “drive reduction.” There were pious murmurs of agreement, and some considered nodding at this and the discussion passed on to the important matter of whether the conference organizers would object if we ordered another round of Weissbier for alles.

Now, I have to admit, I sort of lied to you, dear reader. I was not at dinner with a collection of Very Smart People at all. I was at a psychology conference.

In psychology, for reasons that surpass understanding, it is common for people to take the view that a word—or a pair of words—constitutes an explanation. In my view, Gerd Gigerenzer has put this best. I wrote about his view a ways back, and I think it’s worth quoting him again, discussing one word explanations, along the lines of “drive-reduction,” which I now hyphenate so it’s one word. Gigerenzer writes:

Such a word is a noun, broad in its meaning and chosen to relate to the phenomenon. At the same time, it specifies no underlying mechanism or theoretical structure. The one-word explanation is a label with the virtue of a Rorschach inkblot: a researcher can read into it whatever he or she wishes to see.

Psychologists get trained to think about control groups and statistics and, more and more, topics such as equity—but they rarely get trained to think carefully about explanations. Who has the time for the philosophy of science when one must publish lest one perish?

I mean, the story about the leopard is wrong, but at least it’s an explanation. It is not, however, a scientific explanation. Scientific explanations must have certain properties, though the specific properties they need depends a bit on one’s philosophy. If you’re a die-hard follower of Karl Popper, then for an explanation to be scientific, there must be some observation you could make that would, in principle, show your explanation to be false.

More generally, to be a scientific explanation your explanation should not make reference to supernatural entities or processes and should be consistent with known facts. So, for instance, in the leopard story, the species retains its spots over generations because it was painted at some point, a sort of Lamarkian idea. Thanks to Darwin, we know this isn’t the way species changes work, so the story is, for this reason among others, not really a scientific explanation. (It’s also hard to see how one might falsify it.)

So there are two distinctions to be drawn. The first distinction is between explanations and non-explanations. Kipling’s story is an explanation, as ChatGPT noted. Here is an incredibly simple table, to summarize.

Words, words, words.

Which of the following two questions is harder to answer: 1) why do some people at certain times elect their leaders by polling the majority while others rely instead on a hereditary passage of power, or 2) why do tides rise and fall?

The reason that complexity matters is because more complex phenomena require more complicated explanations. Explanations are models of how the world works and more complex bits of the world require more complex models to explain them.

Now, even simple cases require models. You can’t explain tides with a single word. Sure, you could say “the moon,” but that’s not an explanation. You need more than that. Yes, the moon is relevant, but neither the word, nor the object itself, explains tides.

To explain tides, you need the idea that objects (such as the moon) exert a gravitational force, pulling other objects toward them. (If you want a truly deep explanation, you need an explanation for the gravitational force you just referred to as well.) You need the idea that this force decreases with distance. You need the idea that the moon orbits the earth, so it pulls different parts more than others as it circles. You need the idea that oceans are made of water, which move relative to the ground that holds it. Generally, you need a whole mechanical model that refers to known forces, known facts about orbits, known facts about time, how the water level appears to observers, and probably some other elements.

Note that the explanation for tides depends on the explanation for gravity. A full and complete explanation for tides owes a debt to the explanation for gravity. Thankfully, in this case, gravity is pretty well understood, so much so that physicists have gone beyond a qualitative explanation—more massive things pull harder—to a quantitative explanation, with numbers and everything. The gravitational constant is testimony to just how good an explanation we have. It’s reasonable to pack the notion of a gravitational force into your explanation for tides because the promissory note for that has been paid: gravity is well understood.

The word “moon” is not by itself a good explanation. Similarly, “culture” or “history” is not a good explanation for why Greece is a democracy but Monaco, just across the water, is a monarchy. That black box, “culture,” is also a promissory note—but that box is at worst empty and at best highly disputed, leaving the promissory note unpaid.

DERP

In addition to not explaining anything, one-word answers often have circular logic. Take, for example, extroversion.

Why do some people like going to parties while others prefer quiet nights at home? Well, some people are extroverted while others are introverted. Are these words explanations? At this point, you should be pretty worried.

How do you know that someone is extroverted? Usually psychologists infer someone is extroverted because of answers to questions on a self-report scale that ask questions such as, “Do you enjoy going to parties?”

So… is there any sense in which we have explained why some people go to parties but others don’t? Really all we’ve done is used a word to label what we’re investigating. We’ve said, “those who enjoy going to parties enjoy going to parties.” In my book with Jason Weeden, The Hidden Agenda of the Political Mind, we called this DERPing, standing for Direct Explanation Renaming Psychology, to describe this phenomenon.

This has a direct analog in clinical psychology. I leave this topic to the other Fossils, so I’ll be very brief. Here is how Jonathan Shedler, in a recent blog post emphasizing that diagnoses in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual are descriptions, not explanations, put it:

Here is the circular logic: How do we know a patient has depression? Because they have certain symptoms. Why are they having these symptoms? Because they have depression.

Two Big Words

The word “culture” is almost exactly unlike the word “gravity.” Gravity is the attractive force that objects exert on one another, depending on mass and distance. It’s well-defined and can be precisely measured. The gravitational constant has been established out to eleven decimal places.

Culture… doesn’t have a definition. Or, actually, it has dozens and dozens and dozens of definitions—157, by one count—depending which scholar you ask. Not only that, but there is no consensus—or, heaven forfend, quantitative model—of how culture works.4

As we’ve seen, when someone purports to explain some behavior or pattern of behavior with a single word, you should immediately put your guard up. Especially when that word is used to explain so much.

In recent times, one very popular word to explain various kinds of behavior is trauma. This word has the same cachet that acts of gods used to have. Why did it storm last night? Io once again rebuffed Zeus’s advances so he got mad and threw some thunderbolts around. Pretty much whatever happened, you could offer up the action of a god as the explanation. Today, trauma has similar god-like powers to explain. Why does Billy struggle in Italian class? Trauma!

Interestingly—to me, anyway—trauma is considered by many to be a good explanation for many different phenomena. It’s such an important explanation that one must be trauma-informed when conducting interventions.

How does trauma do as an explanation?

Is it like “gravity,” a nicely filled black box containing a set of well-understood causal phenomena?

It is not. We talk about the units of mass (kilograms, for example) and units of distance (meters, for example). There are no units of trauma.5 (How much trauma did Billy experience? Oh, you know… a lot?) More importantly, there’s no broadly accepted textured theory of trauma. What, exactly, is a traumatic event? How do you know? How does it causally affect future emotion, cognition, and behavior?

Look, I’m not dissing clinical psychology because it doesn’t have a consensual, quantitative theory of trauma. Psychology is harder than physics in many ways. Brains are complicated when they are working correctly. And there are gajillions of ways for them to work incorrectly. So that’s fine.

But.

But… when someone tells you that trauma explains this or that—generational trauma in a particular culture—this is a story. Is it a good story? Is it a scientific explanation? Does it connect to known facts? In the table below, which cell should it properly be put in?

Don’t get me wrong. I do think that some extreme experiences are beyond what our minds were designed to handle, and in those cases, we might expect some sort of reduced function. Related, I wouldn’t be surprised if extremely harmful experiences drastically (and possibly adaptively but possibly not) change one’s tradeoffs. If I was attacked in a dark place or by a particular person, maybe I increase my vigilance in dark places or in the presence of that person. Those changes—updating tradeoffs—seem to be a fairly reasonable response to trauma, bolstered by an evolutionary logic.

I look forward to more explanations like these in the future.

Evolutionary Stories

Here is another story about how the leopard got its spots.

Over the course of many generations, there was variation in color among individuals due to mutation, sexual recombination, and other factors. Individuals whose genes led to coloration that made it more difficult for prey to detect them were more successful hunters which, in turn, led to greater reproductive success than those with genes that were less effective for camouflage. This greater reproductive success led to the spread of these genes compared to alternatives.

This explanation rests atop our understanding of genes, the process of evolution by natural selection, and the way that perceptual systems work.

This connection to known facts and reference to well-understood causal processes makes this story much better than Kipling’s. This explanation is also better than one that relies on the acts of gods, which are neither natural nor obviously subject to falsification.

As a general matter, evolutionary stories are better explanations because they refer to the process of natural selection which, like the theory of gravity, has been well worked out and, among other things, vastly circumscribes the stories that one can offer. (For instance, evolutionary stories won’t rely on “good of the species” arguments, which are unlikely to be correct.) Contrast an evolutionary story—based on a set of principles from the natural sciences, just like the story I told above about the tides—to a cultural story or a trauma story, which has no such foundation.

Given this, why are evolutionary stories, per the interview I mentioned above, seen as less, rather than more scientific, in some circles?

Psychologists

For reasons that surpass my ability to comprehend, few if any graduate psychology programs require that students learn any biology, let alone evolutionary biology, despite having many other difficult course requirements. Indeed, professional scholars are often innocent of any rigorous knowledge of evolution, a pattern evidenced by the overwhelmingly bad presentation of the topic in various textbooks.

Because psychologists are not trained in evolution or the philosophy of science—and because explanations are hard, much harder than most scholars realize—they are unable to distinguish good explanations from bad ones.

The psychologist got confused because they didn’t learn evolution and they underestimated how difficult it is to explain things.

These facts, among others, also explain why this (ill-founded) critique Won’t. Go. Away.

Just so.

I leave the English orthography, as in the original.

This is a bit disingenuous. I understood. Critics didn’t really object on epistemological grounds. They objected to the ideas and manufactured reasons for their objections. Lots of people do this. See Lionel Page’s linked posts for more.

Well, work in the tradition of Rob Boyd offers such models.

Sigh. There is a sense that there is. Some researchers count up “Adverse Childhood Experiences,” which I suppose is a species of quantitative metric.

Great article.

A good label for something is a first step, but only the first step. You must then go on to address causality.

Causality in complex evolving systems can be very difficult to untangle. It becomes even more complicated for entire human societies.

This is how I think about the issue:

When viewed from a very high level, evolutionary processes require two things:

1) Necessary pre-conditions that enable lower-level factors to come into existence and survive and change over time. There are often many different pre-conditions that must come together to create the “Goldilocks conditions.” At any time, the pre-conditions can disappear and the entire evolutionary process collapses.

2) Specific mechanics that explain how that evolution takes place. This usually consists of multiple mechanics that interact with each other in complex ways.

Nothing against falsification, it has been widely used in recent years, however worth reading about how it became famous and does it really help distinguish from science & non-science?

Short answer, NO.

https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/michael-d-gordin-fate-falsification/