After my recent post on willpower, I have been asked why so many theories in the social sciences seem, well, dumb and, as it is turning out, wrong.

Those are good questions and, to my mind, important ones.

The answer lies, I think, where it often does when it comes to human behavior: incentives.

An academic’s success depends on publishing. To get a good job as a professor, you need to publish. The more the better.

In turn, publishing depends on two key criteria.1

First, to be published in a top journal, the work must be new. For example, publishing a replication of prior work is vastly more difficult than publishing new studies. This fact explains why replication has historically been so rare: there’s a very low payoff to the researcher. Many observers of science have wondered about this because in their middle school science classes, they were taught that the foundation of science is replication. The Royal Society’s motto, nullius in verba—take no one’s word for it—is testimony to the point. Science requires checking other people’s results.

Second, in the social sciences and the humanities, the focus of the rest of this essay, work is likely to be published to the extent that it is counterintuitive. If you send a paper to a top journal saying, people like sweet things, you won’t even make it to the peer review stage. The editor will send it back with a polite note that says, in so many words, my grandmother could have told me that. No news.

These criteria put social scientists in a pickle. One problem is that lots of deep stuff has already been said. Aristotle, Machiavelli, Adam Smith… the past boasts some pretty smart cookies.

A second problem stems from evolution. Because good intuitions support survival and reproduction, humans reliably develop intuitive theories about physics, plants, animals, people, and groups that aren’t perfect, but are still pretty darn good. Our intuitive physics allows us to solve ballistics problems with finesse. Our intuitive psychology does an excellent job of predicting what Mary will do if she is hungry and is walking past a restaurant. The power of human intuitive theories, also called folk theories, means that it can be difficult coming up with an idea that is counterintuitive.

In some fields, such as physics, the problem is actually easier in the sense that human intuitions about physics are designed for a world of medium sized objects on a planet with one gee of gravity and an atmosphere that creates wind resistance. Humans have poor intuitions about the very small, such as quantum effects, and the very large, such as the scale of the universe. So physicists’ ideas are often counterintuitive. Biology and chemistry also have areas for which the human mind is not well designed.

In the social sciences, however, because our folk theories are pretty good—that is, our intuitions correctly capture true facts about the world—it’s harder to find something that is both true and, at the same time, counterintuitive. The better our folk psychology, the more difficult the task.

Two scholars recently published a paper showing that people’s stereotypes surrounding men and women are fairly accurate. Many people, previously, made a lot of hay making the (counterintuitive) claim that despite having a lifetime of experience seeing differences in how men and women behave, their beliefs about them—their stereotypes—were somehow all wrong.2 So the field is set up to have an odd cycle. First, publications appear making a counterintuitive claim and then—eventually—correctives appear to show that people’s intuitions are actually pretty good.

Another important piece of the puzzle is the lack of one particular kind of incentive: penalties for being wrong, even luminously wrong. As far as I know, no (modern) scholar ever got fined, jail time, or even fired for publishing a genuinely stupid idea.3 Indeed, in many areas of the academy, such behavior can be richly rewarded. (Working to expose the stupidity of such ideas might be punished, however.) The basic explanation for this is that academics make the rules and they don’t want any that hold them accountable for being wrong. Why would they? Why would anybody?

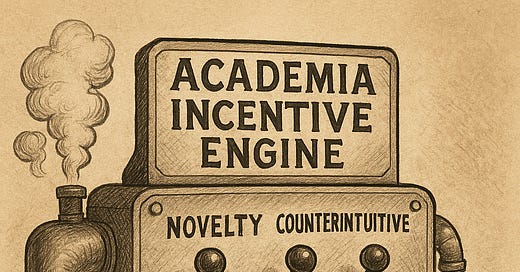

The story so far: Scholars in the social sciences and humanities face incentives to 1) make a novel claim, 2) that is counterintuitive, 3) without worry that the claim might be false, even obviously false.

Now, in some fields, the last constraint is even less relevant. Many people have wondered about a strange idea that spread throughout the humanities and has edged into the social sciences, especially anthropology. This is the idea that there’s no such thing as truth in the first place.4 This helps explain otherwise seemingly bizarre phenomena, such as an academic defending the idea that two plus two might equal five.

My view is that this incentive structure explains a great deal about the social sciences and why there was so little concern for using good scientific practices for so long. If you really wanted to be sure you were right—on pain of punishment—you would be absolutely sure that you used the best possible scientific practices, including large sample sizes, logical control groups, good statistics, and so forth. If you were scared of being wrong,5 you would probably develop ideas that seemed superficially plausible—in line with your intuitions—and you would work as hard as you could not to bias your work in favor of making a claim that would later be shown to be false.

This is not, at all, how the social sciences work.

I note that psychology is a strange beast, as it currently exists in academia. People who call themselves psychologists study, for example, small clusters of neurons in non-human animal brains. That’s fine, but it’s important to remember that no one has good intuitions about which ganglia control feeding behavior. So the incentive to develop something counterintuitive is less binding for our friends in neuroscience. That constraint looms larger as we get to topics humans are better at dealing with, such as differences between men and women.

When I was in graduate school, I was co-advised by an anthropologist, so I wound up attending a fair number of talks in that department. After the inevitable positionality statement and the description of the research site, the meat of the lecture was typically some interesting counterintuitive presentation of the way in which the group the anthropologist was studying differed from the rest of humanity. No one ever started a talk with, “I went to the Amazon river valley and it turns out that everyone there avoids having sex with their siblings and loves their mother.” It was much more likely to be claims such as, they live in perfect harmony with nature and their neighbors, they have 27 words for snow, or they aren’t sexually jealous or possessive.

The incentives to be novel and counterintuitive, with no penalties for error, explain why you see articles that claim that humans have ESP and the notion that willpower is fueled by a mysterious substance in major journals in social psychology. Novel? Check. Counterintuitive? Check. False? Irrelevant.

I don’t mean to single out the field of psychology. It just happens to be the one I’m most familiar with.

My sense is that you can find this dynamic elsewhere. I am not an expert in management, but my sense is that the reason there is a new theory of how to manage employees every few years is for the same reasons: you have to publish as a faculty member in a business school, so you have to say something novel, maybe even counterintuitive. When I went to talks at Wharton, Penn’s business school, the presentations were often animated by theories from psychology from the last decade or so. (Uncharitably, I concede, I used to say that those talks made me feel like business school is where bad psychology went to die. I’m pretty sure I stole this from Jerry Fodor but I can’t find the quote.) I think this occurred because psychology was minting novel theories and business school academics could use them to develop novel ideas in their context. And so it goes.

I have the nagging sense that something like this occurs in history. (I would be pleased to be disabused of this notion if a reader has better insight into this than I do.) My sense is that revisionist history stems from the fact that you can’t make a splash in that discipline by saying stuff like, Hitler started the war because he was a power-crazed maniac bent on world domination, until Churchill, Roosevelt, and their allies stopped him. But you can make a splash by saying, wait, maybe Churchill started it and he’s the villain not the hero. Intriguing! You can’t make a splash by saying, Mao Zedong drew on economically suspect ideas in launching the Great Leap Forward, killing tens of millions of people. You maybe can make a splash by saying, maybe Mao was a great leader whose policies should be emulated…

The incentive to say something counterintuitive might well have driven much of what has bubbled up in history and political science. It’s not a coincidence that the person who characterized the massacre of more than 1,200 civilians as “exhilarating” was a history professor at an elite institution.

In general, because there’s so little new under the sun, the incentive to be novel means that the more you deviate from obviousness and common sense, the better: the holy grail of scholarship in the humanities is not just distortions, but inversions. Refer to the barbarous murderers of babies as heroes. Tar the defenders of humanity and rights, whether in the past or the present, as perpetrators of genocide. Deify the person who condemned millions to death by starvation. Vilify the person who saved millions from death and slavery. Celebrate the dictator. Tear down the liberator.

Others have pointed out the peculiarity that it seems like it’s the Very Smart People who are inclined to believe the Very Dumb Things. Orwell wrote, “One has to belong to the intelligentsia to believe things like that: no ordinary man could be such a fool.” More recently, Thomas Sowell’s take was that “Virtually no idea is too ridiculous to be accepted, even by very intelligent and highly educated people, if it provides a way for them to feel special and important.”

In many ways, these perverse incentives would be academic if the idiocy of the academy were kept inside of it. The problem is that people outside of the academy look to scholars to determine what to believe. (I like the literature on prestige-biased transmission on this topic.)

I recently listened to the podcast, Sold a Story, which provides an excellent and compelling account of debates about how to teach children to read. A core insight of the podcast was that people who used counterintuitive practices to teach children to read—instead of teaching the children to sound out words, as parents intuitively do—report that they were following the lead of academics at institutions such as Columbia. The travesty that is the failure of American kids in acquiring reading skills can be laid at least partially at the feet of scholars chasing a new, counterintuitive idea to publish on. These incentives matter.

Then there is, of course, the political piece. Others have discussed this at length, so I won’t do so here. Still, it’s worth a note that politics generates incentives as well. Because the academy is overwhelmingly populated by people with one particular viewpoint, and because many of those people believe that ideas that don’t fit with their political views must be suppressed, authors are faced with obvious incentives about what to work on and what conclusions they should come to.

All of these incentives, together, lead to the production of scholarship that is novel, counterintuitive, and wrong.

Is there a remedy?

I have no idea. I’m not sure there is an incremental path to a better set of incentives. The people who make the rules are at the top of the pile and they don’t want the rules to change. They’re doing great under the current regime.

My guess is that it all has to be (metaphorically) burned down and rebuilt. Find ways to reward scholars who are boring but right. Find ways to punish scholars—I use the term loosely—who are creative but wrong.

I don’t know what that looks like.

My guess is that the new University of Austin is the way.

In my experience, the present academic system, at least in the social sciences, does not seem well designed to produce truth.

We owe it to future generations to find a way to do better.

There are more beyond these two. One is how important the work is perceived to be. There are others, of course.

his case is an interesting one because it has all the pieces. Initially, people are rewarded for making the counterintuitive claim. This becomes part of the canon. In that context, saying the true, intuitive claim becomes an innovation. I’m not sure if this dynamic is Orwellian, Kafkaesque, or just exhausting.

Historically, you have cases such as Galileo, punished for being too right. Nothing like that happens today, though, right? Right?

I have in mind here Derrida, Foucault, and their many, many subsequent disciples and followers.

Consider how people making rockets proceed. That process is what it looks like when people don’t want to make mistakes.

Congress should define non-partisan as at least 30% Republican & 30% Democrat, and only edu orgs that are non-partisan are eligible for tax exemptions.

Nobody like quotas, but they do work, and nobody has a better idea for Ivy + colleges now.

You are right about incentives, but there is an answer to the grandmother problem, as my old mentor, Bill Brewer, put it. Consider Newton. As I told (I'm retired) my students, if Newton had just said "Objects fall," everyone would have said, "Well, duh." Newton's achievement was showing the exact "how" of falling worked in detail. Is it a function of weight? of distance fallen? Of time? Working out the math so that one could predict events was the real achievement. When challenged that he did not address the why questions of physics (e.g., why do objects travel in a straight line forever unless acted on by a force?) he replied, "I do not propose hypotheses." He equally dispensed with religious angels AND materialist theories like Cartesian materialism. Instead, therefore, of proposing speculative explanations of "duh" findings like "People hold stereotypes," we should answer "how" questions instead. How are stereotypes structured? We can connect them with non-social mental functions such as memory schemas (Bill's specialty) to do so. Early (e.g., 1879-c. 1920) cognitive psychology worked that way. For example, we all intuitively know that we can't grasp everything we see in a moment--a "duh" proposal--but we can quantify how much information can be picked up in brief glances (or listens) and link consciousness to qualities of the stimulus such as time or location of presentation. Or, to take the parent of all psychological research, psychophysics, we can take the "duh" idea that experience of a stimulus such as weight or sound strengthens with increases to the objective mass or acoustic strength of the stimulus, and show that, surprisingly, the function is not linear, but logarithmic, and interestingly maps on to demand curves in economics. These "how" findings are novel, and often counter-intuitive. By the way, folk physics can be unreliable in practice. Pre-Newtonian artillery gunnery was inaccurate; Britain ruled the waves, in part, because a mathematically informed artillery officer worked out artillery tables (a challenging task that spurred the development of the first computers in the US under von Neumann at Princeton) based on proper physical principles. There is a true scientific psychology, but social psych isn't it.