Loneliness, Part II: Solutions to Loneliness

Old and new approaches to basic social connection.

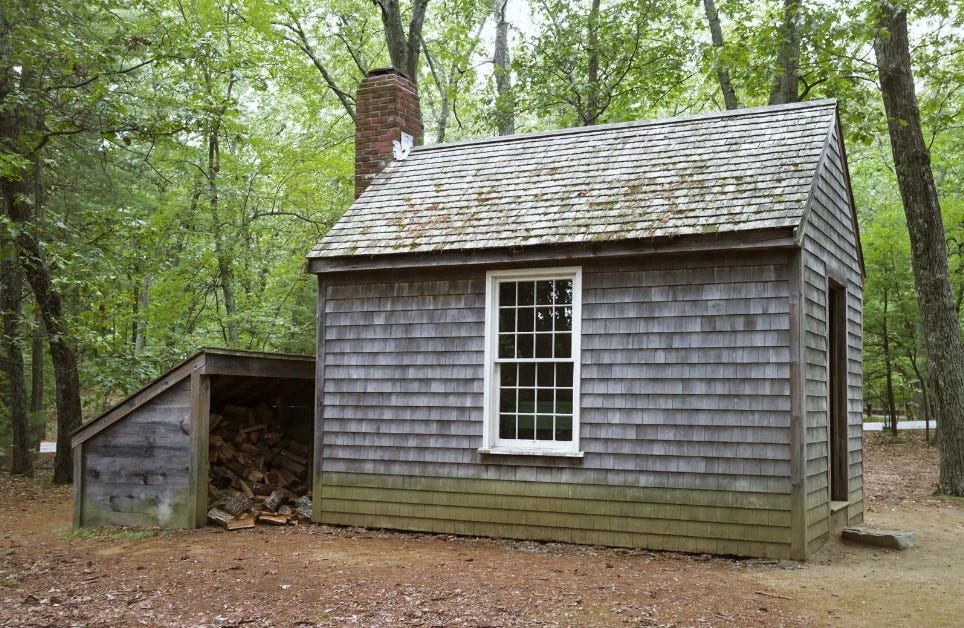

Despite humans’ need for social connection, as evidenced by the feeling of loneliness discussed in the last post, many people occasionally seek—or even generally prefer—solitude. As Thoreau writes in Walden: “I find it wholesome to be alone a greater part of the time.” How do we explain this?

In addition to the puzzle of solitude, this article explores parasocial relationships—one-sided connections that individuals form with media figures, such as celebrities, influencers, or fictional characters—both as these relationships exist currently and how they might exist in the future.

I will argue that while solitude and parasocial relationships offer workarounds to the ancient necessity of belonging to the group, we should be careful about relying on them (or other alternatives) too much. Evolution has given us the blueprint for what sort of connections we need.

Solitude

In Part I, I suggested one answer to why people might find solitude pleasurable: there aren’t any models to compare oneself to on a deserted island, or deep in the woods. A person can have a hard time feeling lonely when they aren’t reminded of it.

Just because a person does not feel bad, however, doesn’t mean their outcomes, from an evolutionary perspective, are promising. Living alone in the middle of nowhere, while removing much of the potential for negative emotions associated with social life—not only loneliness, but also envy, shame, anger, and so forth—sacrifices the chance of social rewards for the sure thing of avoiding social costs. A hermit doesn’t check over their shoulder for what everyone else is doing; they needn’t worry if they said the wrong thing to someone; they don’t have the opportunity to covet what someone else has. However, they also have nobody to check on them if they come down with an illness; no one to lend them money if their cabin burns down; no one to have and raise children with; and so on.

Because group status is so important, humans have plenty of mental architecture to help us navigate the social world. Many of these adaptations lead to unpleasant experiences, as the feeling of loneliness demonstrates. From an experiential perspective, then—which is the one people tend to consciously care about—the basic difference between solitude and society is the degree of emotional volatility. Solitude is a steady stream of medium emotions; society is an unsteady stream of extreme emotions. As Edward Abbey writes in Desert Solitaire, a memoir about his time as a park ranger in Arches National Park: “How could I have forgotten…that the one thing better than solitude, the only thing better than solitude, is society?”

So, on the Totem Pole of The Good Life (trademark pending), perhaps we have solitude resting squarely between a good and bad social existence. By turning off the parts of our brain that monitor the social world, solitude promises an emotional floor at the expense of an emotional ceiling.

Parasocial Relationships

When people pack for a trip on which they’ll spend some time alone, what do they invariably bring? Something to read. Likewise, how is that some people can go multiple days without communicating with a living person? Well, they watch TV, play video games, scroll social media, listen to podcasts, and so on. In essence, they are filling their experience with people, just not real people or people who know about them. These are called “parasocial relationships,” and along with solitude, they can be used cheat our ancient systems designed to measure social connection.

Technically, parasocial relationships are one-sided connections we establish with media figures, such as news anchors, celebrities, podcasters, or politicians. I’m going to extend the term to mean any relationship that is either a) nonreciprocal or b) nonhuman. Your relationship with Frasier is human but not reciprocal, since Frasier/Kelsey Grammer doesn’t know who you are, whereas your relationship with your pet is not human, although it is probably reciprocal. (Personally, I think my cat makes out like a bandit in our arrangement, but that’s another story.) I include these two components because they were necessary for a relationship to be important throughout human evolutionary history. There’s nothing wrong with other kinds of relationships per se; it’s just that there wouldn’t have been selection pressures around those without an impact on individual fitness. (No, a relationship with your favorite Peloton instructor is not an exception.)

Due to technological innovations, the potential for parasocial relationships has exploded over the last 100 years or so—radio, television, internet—and this trend only promises to continue. As much as I hate to write it, AI friends and romantic partners will become a thing in my lifetime.1 There are also more ways to connect with real people than ever. Yet, despite these changes, headlines over the past ten years have suggested that an epidemic of loneliness was well underway before covid came along made it worse.2 The former surgeon-general found loneliness so alarming that he wrote a book about it, comparing its health effects to smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

Is it possible that people are lonelier because they are increasingly relying on “cheaper” forms of connection, such as parasocial relationships? Well, let’s first ask whether people are indeed lonelier than in the past.

Loneliness in the Life Cycle

Despite widespread concerns that loneliness is on the rise—in America, developed nations, or across the world—most claims have been exaggerated. The data is either mixed or the effects quite small.

What does seem stable across time and space is that people are lonelier at certain points in the lifecycle,3 namely between the ages of 16-24 and after 75. Between these two time periods, people increasingly become less lonely. (In fact, it is only because our social groups start becoming sick or dying around 75 that the trend reverses at all.) The observation that young adults tend to be lonelier sometimes leads to the incorrect interpretation that people are getting lonelier over time. But really, the life-cycle effect explains why the average 20-year-old is lonelier than the average 60-year-old.

How do we understand this life-cycle effect? If you’re guessing that there’s an evolutionary explanation, go ahead and pat yourself on the back. You really have been reading along. But what is it? Well, one way to think about it is in the same way your financial advisor (a.k.a. “dad”) thinks about risk. Young investors can tolerate more risk because they have little to lose, much to gain, and plenty of time to right the ship if things go poorly. Similarly, older investors generally prefer less risk because they have more to lose and less time to enjoy additional gains. We can think of this same general approach with “social investments,” also known as “friends,” “family,” “romantic partners,” and so on.

If sociality involves the risk of social cost for the reward of social gain, then perhaps young people take on more risk because they have less to lose and more to gain. Ten years ago, for example, I was without a career and a spouse. I spent an inordinate amount of time thinking about and striving toward those things. Now that I have them, I don’t want to risk them. This attitude cuts a broad swath in my life, and filters down even into my writing: I am much less willing to publish something that might offend someone or cause my reputation to suffer. But ten years ago?—I was a slave to the truth. Alas, these golden handcuffs!

This risk hypothesis squares with the finding that young people tend to have a larger social network and spend more time being social. Young people can afford to take fliers on all sorts of social relationships and experiences—and they generally do, compared to the rest of their lives. And if you are wondering how more sociality can co-exist with more loneliness, remember from Part I that loneliness is expectation minus perception. So, perhaps young people also expect to be incredibly social during this time.

Loneliness in the Future

The data does not currently support an “epidemic of loneliness,” although it makes for fantastic headlines. If a rise is happening, it’s very slight and possibly confined to certain groups, as Jean Twenge and Jon Haidt argue of teenage girls in the U.S. We should also keep in mind that future workarounds could, in theory, solve the problem of loneliness. A techno-optimist might say something like this:

Look, I’ve read your articles on loneliness, which are just great and so well-written, but I have to say, I think you should relax. I agree with you that humans have a bunch of adaptations to help them navigate the social world or whatever, and that some of these cause us to feel bad. But don’t worry! Technology will soon find a way to reliably deliver the positive side of the equation; to stave off loneliness without having to rely on actual interaction with other people, which can be messy. We’re simply living in a Dark Age with this emotional stuff. Eventually, once technology solves these problems, people will look back and wonder that we ever suffered at all.

The problem with this argument is that humans are notorious for underestimating the complexity of the systems they try to improve. I would respond to our techno-optimist with the story of cane toads in Australia. In 1935, Australia imported around 100 cane toads to help them control beetles that were destroying sugar crops. The toads have since lived their best life; without any natural predators, they have exploded in population, and now represent one of Australia’s biggest ecological threats. Oops.

My intuition is that if we try to satisfy ancient mechanisms with novel alternatives, we are going to open a pandora’s box of little-understood downstream effects, which, in scrambling to address, will create more downstream effects…a.k.a. the story of humanity. I plan on writing more about this soon because the fact of the matter is that it’s not just loneliness that humans will try to address with future technology, but every negative emotion associated with belonging to the group.

Conclusion

Real relationships work—that much we do know. Real, of course, meaning human and reciprocal, because these were the kinds of relationships that helped our ancestors pass on their genes. Not only do these relationships stave off loneliness, they make people happier, healthier, more trusting of strangers, more productive—pretty much better off in every way, from an individual and societal standpoint.

Real connections signal to us on a very deep, physical level that we are supported and can relax. Again, this is a potential explanation for the benefit of therapy. Clients often leave with a feeling that could be called “social calm.” The opposite of that—the stress response of loneliness—is designed to motivate us to seek more connection, which is adaptive in the short-term but can cause major, long-term health consequences if it persists.

Technology has made and will continue to make our dependence on others less necessary, but given that humans are far less clever than they think, alternatives to the old ways of relating will likely lead to undesirable, unforeseen consequences. Hopefully, this article has persuaded you that the surest way to social rewards is still by undertaking the risk of a real relationship.

The number of articles on this is staggering. Just Google ‘loneliness epidemic’ and you’ll see what I mean.

That was a really enriching read. I have to say, I find the idea of a life of “medium emotions” quite appealing.