Here’s the thing about verbs like grabbed. When you read them in a sentence, your grammatical mind just screams out for what was grabbed. But what did she grab?! That sentence, above, is unsatisfying. Something is missing.

This post is about moral grammar. If you thought regular grammar was fun, moral grammar is the bee’s knees.

Verbs & Victims

We think about “grammar” as it pertains to language, but a grammar is just a way to talk about rules that let you build complex things from simple parts. The rules of English grammar include the sorts of things that one can use—nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.—and the ways they can be combined, called syntax. Generally, in English, you put the noun before the verb and the order matters: the same three words—dog, bites, man—mean something very different if you reverse their order.

As we see in Did you know that Mary grabbed, when we encounter particular words, our grammatical sense, if you will, is activated. A word such as grab is a transitive verb, meaning it only makes sense if we know something about the object of the action. Mary grabbed a pencil. The pencil was the direct object of the action.

Some verbs require two objects. The verb give is one such. You can’t just say:

Mary gave the pencil.

In this case, your mind is screaming, yes, but who did she give the pencil to? Here, the sentence requires an indirect object as well. Mary gave the pencil to Bill.

English speakers will judge a sentence ungrammatical if the required objects aren’t supplied. Now, these might be implicit. If the prior sentence was, “I recall that Mary gave something to Bill. What was it?” Now, Mary gave the pencil might be an OK sentence because the indirect object, Bill, is implicit. It’s just gotta be in there somewhere.

In sum, when someone hears about, say, giving, a little mental file is opened up with the following structure. I’ll use CAPITAL LETTERS to indicate little slots to be filled in. Those are the categories [e.g., the SUBJECT] that get filled in with specific instances (e.g., Mary, John, the cat.). Here is the structure for the verb give:

[SUBJECT] give [DIRECT OBJECT] to [INDIRECT OBJECT]

The verb just doesn’t make any sense without contents getting mentally poured into those slots.

Identifying grammatical rules of languages was a triumph of modern linguistics.

So far, the study of the grammatical rules of morality is in its infancy.

Indelible Victims

My claim in this post is that morality has a grammar.1

Let’s start with one aspect of it.

There are two ways that researchers have thought about morality. One way is bottom up. The bottom-up approach suggests that, first, people observe the facts of the matter—did someone do something wrong, was someone harmed?—and then, using this information, judge if immoral behavior occurred. Note that in this case the perception of harm is an input to your decision. Seeing harm contributes to your making a moral judgment.

The second way, which we call top-down, is more like the verb case, above. Did someone do something wrong? If so, then I open up my morality template and assume that someone was harmed, just like I assume that if Mary grabbed, she sure as shooting grabbed something.2 Notice here that harm is an output. Your grammatical sense tells you that IF there was an immoral act, THEN there is a harm somewhere, just like the object of a verb. The top-down view is that there is a moral grammar that sort of fills in pieces once you hear about a moral wrong.

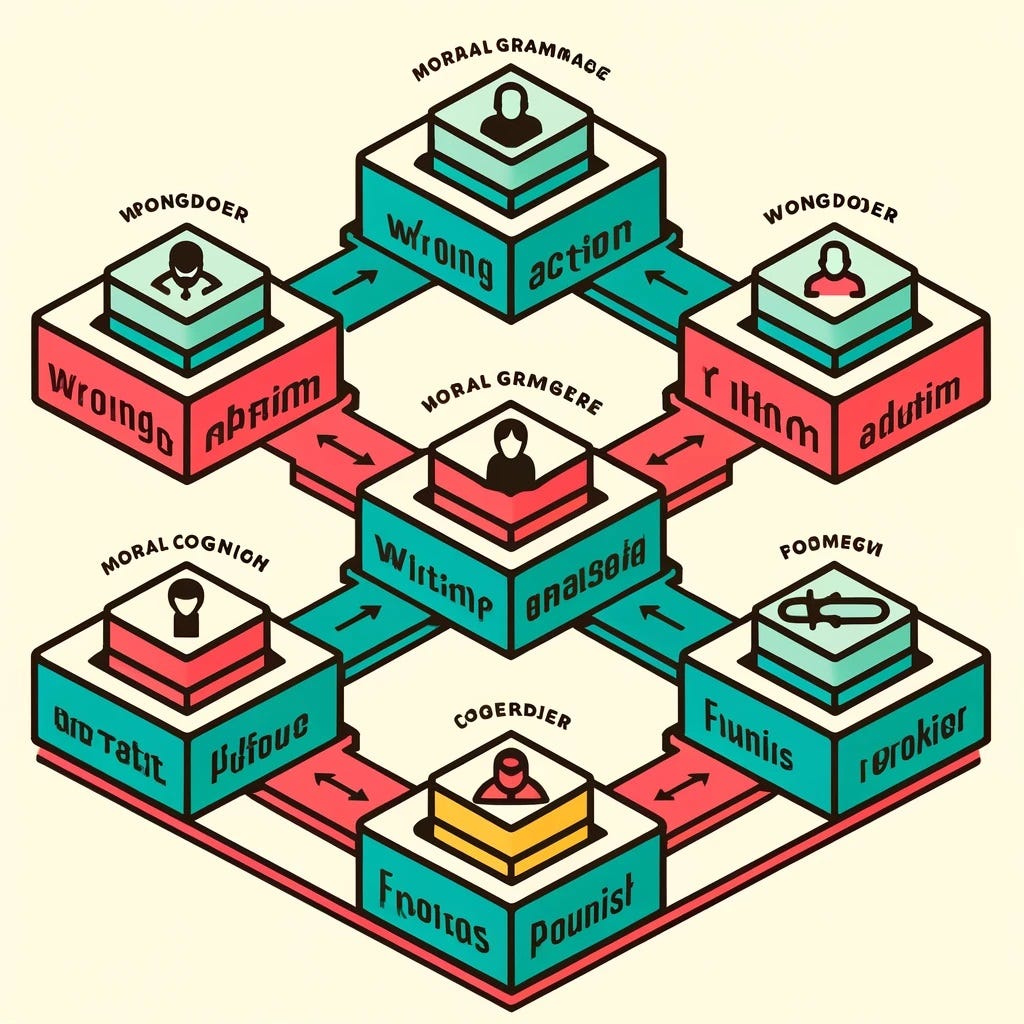

To look at this, Peter DeScioli, Skye Gilbert and I conducted some research a while back to see if there was a moral parallel to transitive verbs. We proposed that when people hear about an action that they judge to be wrong, then, just like a direct object is required for a transitive verb, a victim is required for the moral wrong. Here is the way we put it:

We suggest a top-down account of moral judgment in which the moral faculty can be switched on by a variety of factors that compose cognitive models of moral events… Once activated, moral cognition could seek to fill the remaining slots of the cognitive template with the best available alternatives. These mechanisms could cause people to perceive victims even if little evidence exists for genuine victims or suffering…

So, for instance, if someone thinks stealing is wrong and learns that John stole $5, they will want to know who John stole the money from just as, earlier, we wanted to know what Mary grabbed.

In the same way that give opens up a little model of what happened, with blanks to be filled in, (part of) the moral grammar is:

[WRONGDOER] [WRONG ACTION] [VICTIM]

When we hear what John did, for example, we have:

John stole $5 from [VICTIM]

This moral template helps explain why the first question on your mind when you heard about John was who he stole from.3

Now, if this is right, then it makes a fairly straightforward prediction. Suppose we tell subjects about a number of different actions. Some of these actions will be viewed as wrong by different subjects. Our prediction in this study was that when we tell subjects that a particular act was committed, they would, if they viewed the act as wrong, search around for a victim to fill the slot that just opened up in their head. Crucially, this will happen even if the wrong didn’t actually affect another living soul.

On the other hand, if a subject doesn’t see an act as wrong, then they might say there is a victim, or they might not. Maybe some actions that aren’t wrong still have victims. If I trip and break your vase, then I maybe didn’t do anything wrong, but people might think you’re still a victim.

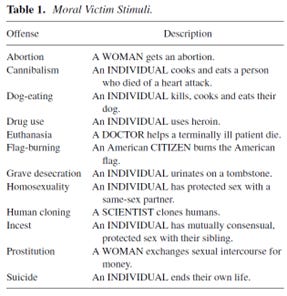

In any case, that’s what we did. We presented a small sample of subjects with potential wrongs such as indicated in this Table:

We presented these to our subjects and then asked them three questions 1) Is this action wrong? 2) is someone wronged and who is it? and 3) should someone punish the person and if so who?

We found a huge effect. If someone said that they thought an offense was wrong, they nearly always perceived a victim and were 43 times more likely to say that there was someone wronged by the action than if they did not think the action was wrong. We also asked people to say who the victim was. Subjects named “the self,” “family,” “society,” and even dead bodies as victims.

Now, the template I indicated above is not the complete moral template. There is also a punishment component. This idea is exactly equivalent to the case in which a verb—such as give—requires both a direct object—what was given—and an indirect object—the recipient. If something is wrong, a little slot opens up, again just like in the case of the word give. The full-blown template looks like this:

[WRONGDOER] [WRONG] [VICTIM], [PUNISH] [WRONGDOER]

Indeed, we found that “when participants judged an offense as wrong, they thought someone should punish 85% of the time, versus 3% when the offense was viewed as not wrong” (p. 145).

These results might in part help to explain why people who study morality have focused so heavily on harm. If this grammatical view is correct, then the judgment about whether or not something is wrong might come before people consider whether someone was harmed.4 People read the vignette, decided if the action was wrong and, if so, the [VICITM] file opened up and they tried to fill it.

In short, while you might have thought that people’s moral reasoning goes like this:

IF there is a victim THEN a wrong was committed,

It looks like—at least some of the time—the causality is reversed:

IF a wrong was committed, THEN there is a victim.

Basically, moral grammar requires a victim. It seems that as soon as one believes that a wrong has been committed, the full grammatical structure is prepared. Mary grabbed… what? John masturbated… who was the victim???

Is this all, well, academic?

Maybe.

Donald Trump, with whom some readers might be familiar, was charged with a crime, specifically fraud, misrepresenting his wealth and assets. A New York court judged him guilty of this offense, assessing a tolerably large punishment for it.

Who, exactly, was the victim? According to reporting, the false claims about wealth did not affect the terms of the loans from the bank, which was, in any case, repaid in full. The Wall Street Journal reported:

Bankers from Deutsche Bank, which lent money to Mr. Trump, testified that they were satisfied with having done so, given they were paid back on time and with interest. They also testified that they were uncertain whether the alleged exaggerations would have affected the terms of the loans to Mr. Trump—a key part of Ms. James’s case. Since there were no victims, the state will collect the damages.

In short, this seems to be a case in which there is a wrong but no actual victim. But there was, of course, punishment.

Indelible Perpetrators?

So, it looks like people go from wrong à victim. Do people also go from victim à wrong?

They seem to. Kurt Grey and colleagues reviewed evidence in the literature to that point and suggested that when people see that someone is suffering, people “infer the presence of another mind to take responsibility as a moral agent” (p. 111). This suggests that not only does seeing a moral wrong activate one’s full-blown moral grammar, as indicated above, but seeing suffering can do so as well.

Indeed, this happens all the time. Remember when Hurricane Katrina levelled New Orleans and certain people claimed that the destruction was retribution for behavior the speaker didn’t approve of? More generally, historically, all sorts of acts of nature have been ascribed to the action of supernatural beings visiting punishment on mere mortals.

The fact that suffering can be used to open up a moral template among observers might help to explain some interesting trends. If it’s true that a claim of suffering invites observers to hunt for someone to condemn, then moral entrepreneurs, let us call them, can enact suffering to recruit others.

So, a claim about there being a VICTIM of a wrong automatically leads people to look for a PERPETRATOR. If one hears that such and such a person is a victim, then the hearer opens up their grammar file and searches around for a PERPETRATOR.

This idea is exactly parallel to the indelible victim effect. That effect was

If [WRONG] then [VICTIM]

The indelible perpetrator effect would be:

If [VICTIM] then [WRONG]

In both cases, the inference is due to the way that morality is grammatically structured, as indicated above:

[WRONGDOER] [WRONG ACT] [VICTIM]

Again, is this all academic? Do people, generally, know that if they can persuade others that they have been harmed then they can motivate attacks on the supposed perpetrator? If so, do people in the real world claim victimhood, perhaps in the service of implying that there is, somewhere out there, a perpetrator who is responsible and should be punished?

Consider this short video, depicting generational differences. First, a man bumps into a wall, and just shrugs it off (born in 1970, my generation 😊). Then, the 1980 man bumps into a wall, then yells at the wall. The man born in 1990 bumps into the wall and shows some outrage at the injustice. The man born in 2000 bumps into the wall, theatrically falls in agony and quickly records his suffering with his phone, presumably to post to social media.

Why the change? One possibility is that in 1980, when you bumped into a wall, you didn’t have a device to broadcast your (alleged) discomfort into the ether. Now, of course, everyone has such a device, which can be used to communicate any pain you (allegedly) feel, broadcasting it to your friends, allies, and followers.

If the above analysis is correct, then one possibility is that claiming victimhood can be used as a recruitment device.

Suppose that one were in a culture in which, for whatever reason, there was a torrent of claims of victimhood. That is, suppose there was some set of people who were constantly claiming that they were victims. Use your imagination.

Now, in such a culture, if the above is right, then the other grammatical components would be everywhere as well. Remember that claims of victimhood automatically open up the full grammar of morality, with a perpetrator, victim, and need for punishment.

So, in a world in which everyone’s feelings were being hurt, at the same time there would also be perpetrators everywhere and there would be wrongs everywhere. Now, one could imagine that the perpetrators might not always be aware of what they are doing—perhaps their wrongs are implicit or even systemic—but those responsible would be, nonetheless, perpetrators.

This view predicts—or, I suppose, explains—why cultures of victimhood are also cultures in which there are pervasive claims of harm and relentless attacks on putative perpetrators.

Note an important consequence of this possibility, if it’s true.

As I’ve discussed elsewhere, it’s important to keep in mind that an accusation of a moral wrong can be usefully understood as an attack. Because the grammar of morality includes the idea that punishment should be imposed, to say that there is a wrongdoer is to make a claim that someone should be punished.

For this reason, a claim of victimhood is, grammatically, an attack.

A claim of victimhood is to invite others to “fill in the blank,” just as in the case of Mary and whatever it was that she grabbed. To say, “I was harmed,” is to say, “someone has committed a wrong.”

And the larger the claim of victimhood—that not only was I harmed, but I was grievously harmed, even traumatized—the larger the attack.

We’ll return to the possibility that a claim of grave harm is best understood as a demand for harsh punishment in the next post in this series. So stay tuned!

This view resonates with the intuitionist account that Jon Haidt and colleagues have developed.

There might be other reasons you care about this, of course. In the case of theft, you might want to know if it was theft from a friend, enemy, or neutral party. My claim is not that there are no other reasons you might wonder, but that the grammatical approach implies that you generally will.

You had me at the "grammar"!!!!

GM: I think there are three corollaries to this theory worth exploring:

1. this moral grammar confirms my opinion (https://open.substack.com/pub/thelivingfossils/p/morality-is-a-coordination-game-coordination?r=1m606h&utm_campaign=comment-list-share-cta&utm_medium=web&comments=true&commentId=53617106) that morality has always a rational origin, i.e. a bottom-up evolution,

2. this explains also why depenalisation starts with the theorization of "victimless crime" (e.g. "'e dindu nuffin", "maaan imma only smokin' a joint"),

3. this MAY explain why secularization harbrings moral relaxation, i.e. many folk-interpretation of moral law identifies the victim with God ("Jesus cries" is a common folk catholic trope).