In a prior post I discussed how billions of cicadas emerge every seventeen years, playing what amounts to a coordination game, a situation in which players benefit from matching what other players do. Because predators get satiated from eating so many darn cicadas, it is beneficial from the perspective of each individual cicada to emerge when others do and enter a world with predators who aren’t hungry for more. It’ll be easier to work your way though this post if you’ve already read the prior one.

To review, here is a coordination game in which Adam and Bob must choose a lane to cross a bridge. The two players are indifferent to which side they wind up on but care a great deal about choosing the same as the other player. Here and below, I use green font to indicate equilibria, outcomes of the game in which a player can’t do better by switching to a different strategy.

This example has a parallel in the real world. As is well known, the convention to drive on the left or the right—not just on bridges, but pretty much everywhere—varies around the world. In the Americas and continental Europe, the convention is to drive on the right. On some islands—e.g., England, Japan, and Australia—the convention is reversed. The fact that the exceptions are islands is not a coincidence: People on the island only have to coordinate with each other, not the rest of the world.

How did the convention to drive on the right come about? There are many forces at work dating back to the days when horses drew carriages—here is a recent piece on this—but for the present purpose what matters is that as this convention emerged, each individual driver had an incentive to follow it. No advantage could be gained by switching to the other side.

Traffic signals are also coordination devices and the logic is the same. Sure, red could have been used to signal go and green could have been used to signal stop. The key point is that all drivers move depending on the color, coordinating their movements. Just as in the side of the road case, there is a cost to switching strategies. Going on red might sometimes get you there faster, but, eventually, using that strategy will not end well. This sort of coordination is called a correlated equilibrium: players all use some signal in the world to choose their strategy, knowing others will as well. (Compare this to driving on the right: everyone uses this strategy all the time, so there is no need for a signal to coordinate movements.)

The last post laid out the logic of coordination games, explained how you might recognize when you are seeing a strategy designed to win a coordination game, and provided some fun examples among our non-human friends. This post considers coordination games in humans.

Language

At its core, the value of language is that it allows me to move an idea in my head to yours, often—but not always—incredibly efficiently.1 As others have pointed out, this makes language the ultimate coordination game. If I want to get an idea from my head to yours, I need to wrap the idea in words. If I use a pumpkin to mean something that you do not understand it to mean, then my goal of communicating the idea suffers, just as it did when I substituted the word “pumpkin” for “word.” My goal as a speaker is to use words in a way that corresponds to the idea that listeners attach to words and phrases. As Levinson put it, the key to communication is “the speaker finding the signal that the recipient will interpret just as the speaker intended” (p. 53).2

Now, it’s important to recognize that I’m not saying that language is a pure coordination game. There are, to be sure, instances in which speakers want audiences to be uncertain about what they have in mind. Pinker highlights that a speaker who invites another person up “to see their etchings”—a euphemism for a more intimate proposal—might want to be able to deny the idea that is genuinely in the speaker’s head in case the invitee does not, in fact, wish to see etchings.3

Complicating matters, language involves lots of inferences. If you say “yes” when I ask if you can pass the salt, there has been a failure to communicate. The best book on language, in my opinion, remains The Language Instinct which treats these and other issues with finesse.4

By and large, however, language works because the sound that I use to mean the animal from which we get milk, a cow, is the same sound that you use to refer to that animal. By stringing sounds together in the proper order, I can move an idea in my head to yours. So, if I would like you to point your mouse at a particular part of the screen and take a specific action, I can write the words, Please like and subscribe!, adding a punctuation mark to convey another idea, namely my enthusiasm for the possibility you might take these actions. (Please like and subscribe to The Living Fossils!)

Now, holding aside etching cases, it should be clear that in playing the language game, just as in the driving case and the cicada case, I gain no advantage by deviating from using words the same way others do. Under most circumstances, all that would do is create confusion about what my pumpkins5 mean.

Now, just as in the firefly case, there are forces that push things around. For example, languages tend to have short words for ideas that are used frequently—I, he, is, go, be—and less frequently used words get saddled with longer sound sequences. Rehabilitated. Prestidigitation. This process is called equilibrium selection. You can think of the forces that make some equilibria more likely as “attractors,” pulling players to some coordination points more than others. As Thomas Schelling pointed out in The Strategy of Conflict, some coordination points are natural or obvious equilibria. A price that ends in $.99 is a good example.

Note that coordination games are local affairs. As languages evolved and changed, groups of people who communicated with each other developed sound/idea mappings, leading to clumps of people who speak English, Russian, Japanese, Bantu, and so on. Each group of people wound up on some set of language equilibria. These sound/idea mappings, then, were homogeneous within groups, but—because it’s a coordination game with many different equilibria—different between groups. Still, across languages, frequently used words tend to be small and there are many other regularities across languages (again, see The Language Instinct) that are there for one reason or another.

None of this is to say that word usage is perfectly coordinated among all speakers of the language. Some people call them fireflies, some call them lightning bugs. In Philadelphia, you people over there are you, or maybe youse, but in Houston, you all are y’all. There are regional dialects.

And, finally, sometimes people fight over what a word means, especially when the meaning has tangible effects on people and groups. I remember when there was a heated debate about the meaning of “marriage.” More recently, there have been debates about who or what is a “person” and who meets the definition of “woman.” And, as Steve Pinker discussed in The Stuff of Thought, what counts as an “event” was very consequential for the insurance companies in the wake of the attacks on 9/11 because the policies paid per event. Was there one (coordinated) attack or two attacks (on two different buildings)?

Some coordination games don’t leave everyone equally satisfied, especially when the coordination point has differential effects on the players. Consider the Battle of the Sexes, a game in which two people want to do an activity together but have different preferences about which one. Here, Donna and Carl want to spend time together—they get a zero payoff for dis-coordinating—but Donna prefers to hike while Carl prefers a movie. Coordination games, in short, can also involve conflict, often visible in preferences over different equilibria.

To sum up:

The explanation for why humans have language at all is the benefits of moving information.

The reason that people who live near one another share the same sound/idea mapping is because they are solving a coordination problem. You can’t move information without using the same sound/meaning pairings.

The reason that different groups wind up with different mappings of sounds to meanings is because there are multiple equilibria. A horse is a horse of course of course, but it could have been un cheval.

There are similarities among languages, often because there are equilibrium selection forces that result in similar outcomes. People seek efficiency, so little words are used for common ideas.

There can be ongoing conflict about equilibria, often because some equilibria are better than others for some players. Which equilibrium is selected might have to do with questions of power, a point to which we’ll return in the next post in this series.

Recognizing Coordination Games

Humans play a number of coordination games. There are reputational benefits to wearing clothes that have the cut, fabric, and color that correspond to what others are wearing. It’s good to be seen as having a sense of style. There are also benefits to consuming the same media, art, and entertainment others are. Doing so connotes “taste.” Similarly, adopting and signaling that one has adopted the beliefs that others of one’s group hold can be important for group membership and one’s reputation as a good group member.

Still, just because everyone is doing the same thing doesn’t mean that they are playing a coordination game. For example, technologies often converge. Wheels are round everywhere. This fact has to do with what wheels are for and the shape that best accomplishes rolling. These sorts of cases don’t have to do with the benefits of doing what others are doing. Observing similarities does not logically entail that you’re observing a solution to a coordination game.

So what are the signs?

As a general matter, coordination games arise because there is some problem to be solved by multiple individuals doing the same thing, even if the content of the thing that all are doing looks arbitrary in some way. This might be species-signaling, in the firefly case; communication, in the language case; or signaling group commitment, in the supernatural belief case. (See below.) So, one clue is observing within-group similarities and between-group differences in these contents, especially if there seems to be some element of arbitrariness to them. Obviously, this applies to many cultural differences, and, indeed, many things that we associate with culture are well understood as coordination games, from which side of the road to drive on to languages to fashion.6

Remember too that if there are a large number of equilibria, not only might you find some arbitrariness, but some equilibria might look downright bizarre. A consistent feature of coordination games is that if you land on a local maximum, it can be tough getting off of it, even if there is a much better maximum to be found. Somewhere along the line, there was a good reason to wear a tie, I’m sure, but now we seem to be stuck with the convention, which those of us who are not especially dexterous find vexing.

Finally, many human universals, such as parental love, are unlikely to be the result of a coordination game. We have an excellent explanation for this phenomenon, and that explanation is not to do with coordination.7

The trick is to figure out which game the organisms are playing, including where the benefits from coordination lie.

A point to which we will return.

OPTIONAL CODA

Supernatural Beliefs

Here is one bonus example, for those who can’t get enough coordination games.

I’ve written about supernatural beliefs before because I think they are so instructive.

For this section, I assume that 1) all supernatural beliefs are false, 2) believing the truth is useful—if I correctly believe the post office is at Main St. and 6th Ave, then I can accomplish my goal of mailing this letter—and 3) people use supernatural beliefs to signal their commitment to groups.

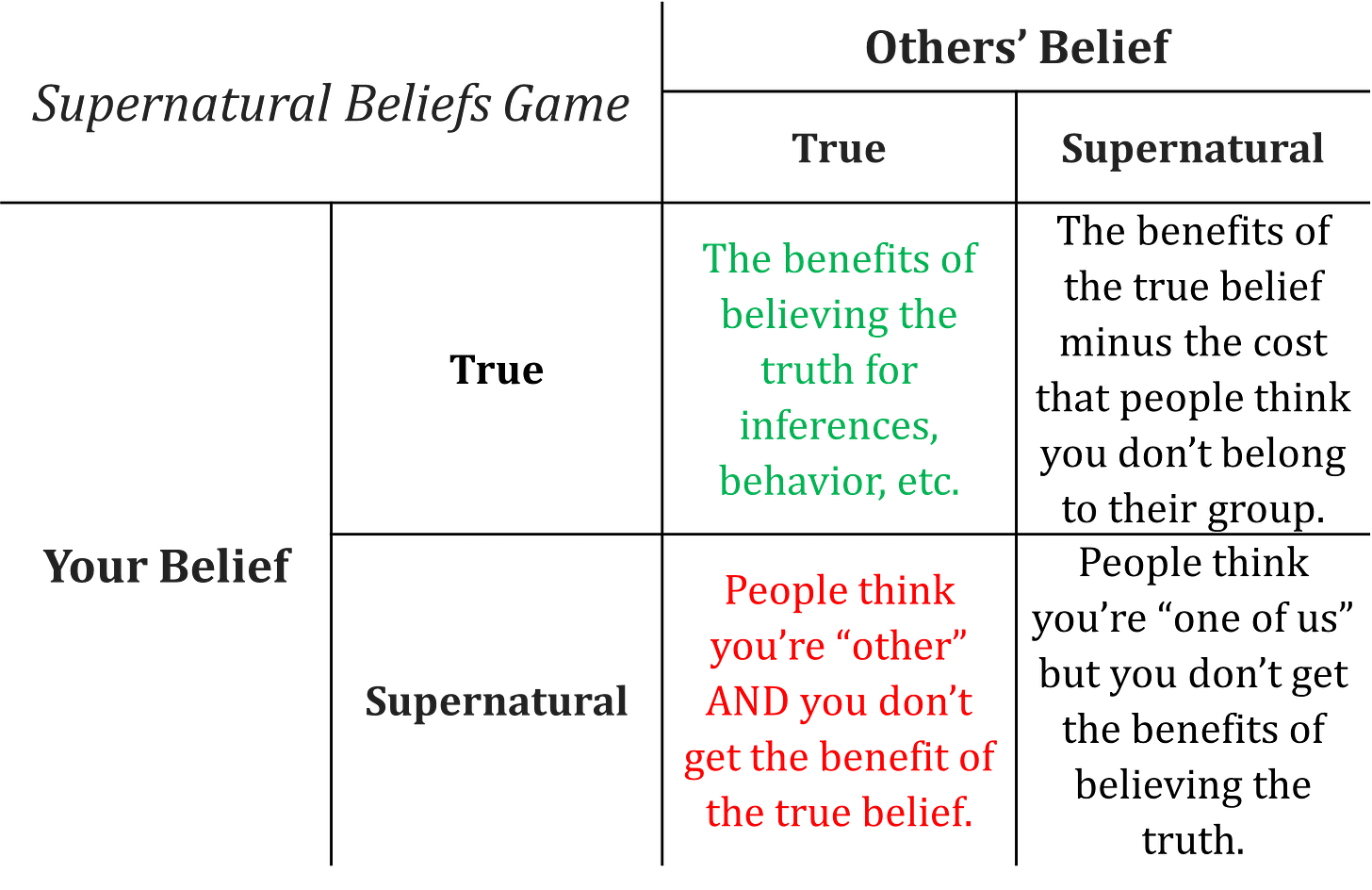

Here is one way to view your payoffs of the Supernatural Belief Game

It should be clear from this structure that whether or not you endorse a supernatural belief others hold depends on, first, the value of having the true belief for going about the world and, second, the value of being seen as belonging to the group.

This analysis explains why people often adopt the (false) supernatural beliefs of those around them. This tendency should be especially strong when the benefits of having the true belief are modest. How much does it harm you to have the wrong belief about the origin of the universe, whether it was the big bang or that Odin used Ymir’s body for the act of creation? Reciprocally, adopting the local supernatural belief should be especially strong when the costs of being seen to be outside the group are high. Consider cases in which heresy or apostasy are punishable by death. In such cases, coordinating supernatural beliefs is vital.

This analysis suggests people will wind up in the black quadrants. If adopting a supernatural belief undermines inference or behavior in some tangible way, then the best move might be to dis-coordinate. If you want to live a promiscuous lifestyle, then you might reject the belief of those around you that the infinitely powerful guy punishes people who don’t save themselves for marriage.

Just as in the case of language, there are some forces that act to select supernatural belief equilibria, which explains why there are similarities among different cultures’ belief systems. Supernatural beliefs tend to be ideas that are familiar—people, animals, plants—but with an exception. A tool… that has beliefs. A plant… that can see. An animal… that can talk. A person… who doesn’t die.8

Just in the case of language, there are fights over supernatural beliefs. One could argue that much of the conflict in Europe from the 16th to the 18th century were driven by such fights. Indeed, many current conflicts are animated by different supernatural beliefs. Even when there are benefits to coordination, that doesn’t mean there aren’t other costs and benefits that will influence decision making.

To sum up:

The (putative) explanation for why humans adopt (false) supernatural beliefs is the benefits of signaling commitment to a group.

The reason that people who live near one another share the same supernatural beliefs is because they are playing a coordination game.

The reason that different groups wind up with different beliefs is because there are multiple equilibria, different mixes of supernatural beliefs.

There are similarities among supernatural beliefs, often because there are equilibrium selection forces that result in similar outcomes.

There can be ongoing conflict about equilibria, often because some equilibria are better than others for some players.

REFERENCES

Boyer, P. (2003). Religious thought and behaviour as by-products of brain function. Trends in cognitive sciences, 7(3), 119-124.

Levinson, S. C. (2000). Presumptive meanings: The theory of generalized conversational implicature. MIT press.

Pinker, S. (2003). The language instinct: How the mind creates language. Penguin.

Pinker, S. (2007). The evolutionary social psychology of off-record indirect speech acts. Intercultural Pragmatics, 4(4), 437-461.

Sally, D. (2003). Risky speech: behavioral game theory and pragmatics. Journal of pragmatics, 35(8), 1223-1245.

Schelling, T. (1960). The Strategy of Conflict. Harvard University Press.

Wittgenstein, L. (1958) Philosophical Investigations. Basil Blackwell, Oxford.

George Bernard Shaw quipped that “England and America are two countries separated by a common language.” I recall being struck by an anecdote Churchill tells in his account of World War II when Americans and British generals were arguing over whether a topic should be tabled. They actually agreed. But the issue arose because in American English, to “table” is to put off, whereas in British English, to “table” is to put up for discussion. Hilarity ensues.

See also Wittgenstein, 1958, Schelling, 1960, and Sally, 2003.

Pinker, 2007.

Another excellent work is Wilson and Sperber’s Meaning and Relevance, aimed at a more academic audience.

See what I did there?

As an exercise for the reader, what are some other examples in which there are universals and variation?

I have the theory of kin selection in mind here.

For excellent accounts, see the work of Dan Sperber and Pascal Boyer.