The bulk of human evolution occurred well before the pyramids, before writing, and even before agriculture. Similarly, countless traits evolved well before the anatomically modern human and are found in other organisms, too, such as eyes, sexual reproduction, and nervous systems. Even when these features are tailored to Homo sapiens, they share an ancient origin with homologs across the biological kingdom.

Now, you might think this evolutionary history has little to do with today’s mental health issues—and if our knowledge of the brain were as comprehensive as it is for the rest of our body, you would be right. Your physical therapist, for example, could sprinkle in a little history about the human knee, including its historic use and structural evolution, but it wouldn’t be necessary for your rehab. In fact, it wouldn’t even be necessary for your physical therapist to know it. While the phylogenetic history of the knee is well understood, you don’t really need it to fix one.

Scientific efforts on the brain haven’t netted psychologists the same amount of practical, usable knowledge, which is why—in my opinion—the mental health industry must step back to move forward. How was the brain supposed to be used? What was it for? Only with a framework built around function and design can we begin to meaningfully troubleshoot problems that arise.

A Punch List for Mother Nature

Put yourself, for a moment, in the bare feet of a prehistoric person. This person would have woken up in their hut, cave, hovel, or whatever—and looked out into a state of nature. Outside of a few rudimentary structures and minor modifications, such as clearing of brush and piling of scraps, the environment would have contained nothing human-made.

Something approximating a state of nature still exists in some places of the world. I’ve visited a few of them. (America’s national parks are incredible, but please stay away. I’d like them for myself.) What might stand out to the uninitiated about these places is their messiness, for lack of a better word. Water spilling over banks, half-dead branches hanging from trees, wet leaves mucking up the soil, and so on. A modern person, accustomed to living in cities or suburbs, might see a lot of room for improvement.

That said, every animal would have a punch list for Mother Earth. Anteaters might petition for global soil aeration. Whales might prefer the entire surface to be covered in water. Giraffes might request that all fruit grow above a certain height. Cockroaches are still waiting for that nuclear holocaust we’ve all heard they’ll have no trouble surviving…

Humans have their own set of preferences. Our prehistoric person, for example, might have desired:1

To keep game close by—perhaps in a pen—rather than having to go out and chase it (or migrate alongside it)

To have chill game that didn’t react strongly to being captured and killed

To create fire at the snap of a finger—one that could perhaps cook food evenly

To keep homes dry and at a certain temperature, no matter the weather

To have something soft and level to sleep on

To have light when the sun couldn’t provide it

If our prehistoric person could be brought into the present moment, their initial reaction might be one of stupendous delight. The original state of nature was pretty inconvenient, they might conclude after a week. Good thing we renovated.

Humans are the best environmental tailors—or niche constructors, to use the technical term—that exist. (Take that, beavers!) Generally speaking, this A-plus level niche construction has been a boon for our kind, but there have been drawbacks, too, and and not only for the organisms in our way. (Suck it, wooly mammoth.) Humans might have built such a nice home for themselves that they won’t have one for much longer. And this home, despite the rough product of our desires, has nevertheless been a breeding ground for evolutionary mismatch—which, at this point, will probably be on my tombstone.

Josh Zlatkus

b. 1988

Loving husband and father

Champion of evolutionary alignment

Evolutionary mismatch, like water in a house, has spread much farther than we think. And this is a result of how humans have chosen to modify their environment—“for the better.” Let that sink in. We are responsible for our own evolutionary mismatch. Time will tell if the tradeoff has been worth it.

At any rate, let’s dive into an example of just how subtle and far-ranging effects of evolutionary mismatch can be—by investigating OCD.

Straightlining OCD

We need to keep an open mind about what mental disorders are, fundamentally, because our knowledge of the brain is much less complete than our knowledge of, say, the knee.

It’s entirely possible that some mental disorders did not exist—or did not exist anywhere near to the same degree—in environments of evolutionary adaptedness. It’s plausible that some mental health issues would largely go away if humans returned to a state of nature.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) might be one such case.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), people with OCD have persistent, unwanted thoughts (obsessions) and engage in repetitive behaviors (compulsions) to quell the anxiety those thoughts produce. The classic example is someone washing their hands frequently to soothe anxiety about germs. Another is muttering prayers to ward off sexual or violent thoughts.

Now, my argument for how human-made environments have exacerbated or even created OCD involves straight lines, level surfaces, organized files, and symmetrical displays. You know, stuff our ancient person would have had little exposure to. My argument also turns on Rob’s definition of dissatisfaction as something that’s close to satisfying, but not quite.

Alright, I’ll leave it there. Surely you have enough to piece it together.

Aha, what was the feeling you had just then? My guess is that you felt a tug of dissatisfaction. A churning sense of incompleteness. I brought you close enough to my thesis that you could smell it, but not close enough that you could taste it. Indeed, if I left you there, you’d be worse off—emotionally—than if you never started this article.

Ok, enough beating around the bush. The point is that a bush, by its very nature, does not always grow where you want it to. It does not develop perfectly evenly. It’s not precisely symmetrical. But the driveway that the bush is planted next to? It’s pretty darn flat. And the window above it? Remarkably level. And the line of spruce trees on either side of the bush? Three to each side, all of the same height.

Stuff that humans make adheres to humans’ preferences for straightness, symmetry, balance, and order much more than stuff nature makes. Go figure.

So what’s the problem? The modern world, in being almost a perfectionist’s dream, creates perfectionism. To see why, we have to return to a finer point of Rob’s article on satisfaction and dissatisfaction:

So satisfaction has what seems to be something of an uncanny valley. If the stimulus is far from “right,” then it’s not really satisfying or unsatisfying… [b]ut as it gets close to right but just misses, it’s very unsatisfying, and then leaps up to very satisfying as it matches the solution state.

A home in the throes of renovation is neither satisfying nor unsatisfying, but as it approaches completion, the homeowner goes through a phase of dissatisfaction before (hopefully) reaching satisfaction. An uncentered window, nick in the brand-new floors, or sloppy bit of painting can drive a person mad—until they’re fixed. Then satisfaction reigns.

How does this apply to OCD? The modern person is subjected to more feelings of dissatisfaction because world contains so many straight lines, symmetrical configurations, and so on that exceptions stand out and irritate more. At the same time, for just a little work, there is plenty of satisfaction to be had. You caulk the only gapped edge in your house and feel like a million dollars. You blow your neighbor’s leaves to the edge of the street and await an award from the township. You organize your Tupperware drawer and decide to run for Congress.

Remember, the state of nature in which humans evolved was messy. It did not conform to all, or even most, of our aesthetic preferences.2 This means there was less opportunity for dissatisfaction and satisfaction. The satisfaction program was just much quieter. Again from Rob’s article:

…as one gets further and further from a good match between one’s sense of the goal state and the actual state, you just don’t see the thing as possibly done. It’s not a candidate to be satisfying because you don’t even recognize it as trying to be at the goal state. So as things diverge, it’s less unsatisfying because your satisfaction system isn’t even bothering to judge whether it’s a good match or not.

Simply put, environments of evolutionary adaptedness weren’t close enough to a goal state that humans felt compelled, via the emotion of dissatisfaction, to fix them.

Illusions of Control

I’m not arguing that the predisposition for OCD was absent in our ancestors. (Given how slowly evolution tends to operate, it was likely present, although see here for qualification.) Instead, I’m saying that modern environments provide more grist for the OCD mill. Modern environments might be similar to nearly renovated homes—uncanny valleys in which things are close to perfect, but not quite.

Not only are modern environments almost complete, thus tripping our dissatisfaction sensors, but in many cases people can do something about it—and get satisfaction. A person today can whip out a level and make sure the air pocket is perfectly between the lines. They can order a fourth hook for the right side of the sink because the left already has four. They can buy a hedge-trimmer for the row of hedges along the sidewalk.

Our ancestors, by and large, lacked these abilities.

For example, let’s give our prehistoric friend both a name (Reed) and predisposition for OCD. And let’s give him a stone to sit on that isn’t quite flat. The first question is: will he notice? Will Reed class this as a “problem”? The second question is: can he do anything about it? If Reed’s answer to either of these questions is no, then his mind is likely to move onto other matters.

Now, we’ve already seen why Reed is less likely to perceive his crooked sitting rock as a problem: nothing else is perfect or close-to, either. The fire ring isn’t exactly circular and the hut is missing some fronds. Hell, Grog over there doesn’t have any front teeth.

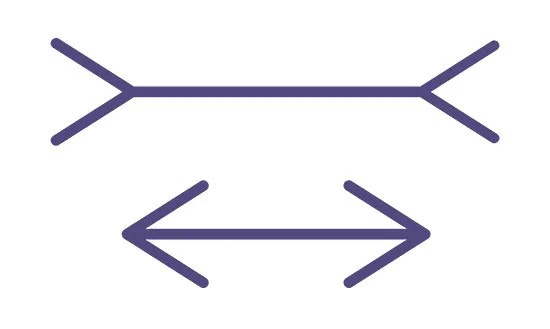

Believe it or not, the ability of the surrounding context—including culture—to influence perception applies even to optical illusions. It would be reasonable to assume that illusions such as Müller-Lyer’s (below) would trick anyone with an eye—but research has found that individuals from cultures with environments that have fewer straight lines and right angles are less susceptible compared to those from industrialized societies. Findings like these suggest that many modern problems—say, an uneven sitting surface—are not inherently problematic, but rather depend on the context.3

For the sake of argument, though, let’s pretend Reed is unhappy with his chair. The second consideration is: what can be done? He could tramp through the woods in search of a flatter stone, but will that really be worth the effort for a temporary camp site? And what are the odds of success, given that nature doesn’t make stones to order?

The difference between renting an apartment and owning a home provides a modern corollary to this kind of cost-benefit analysis. People feel much more compelled to fix their homes than their apartments despite being just as capable of noticing an unlevel outlet plate in either.4 The difference is in the second step of asking whether it’s worth it. Those living in an apartment tend to let more go because they won’t benefit from improvements nearly as much as in a home. Can the same be said for our ancestors’ temporary abodes, not to mention their lack of Amazon’s same-day delivery?

Here’s the bottom line: the spiral of thoughts and actions that characterizes not only OCD, but many anxiety-base disorders, can be avoided altogether if the thing in question is not classed as a problem. If it is classed as a problem, though, then the mental effort of fixing it can be short-circuited if the fix is impossible or clearly not worth the effort—as would be the case, I think, with an uneven sitting stone in the state of nature.

Of Mice and Wheels

Environments of evolutionary adaptedness deviated far enough from humans’ aesthetic preferences that, by and large, our ancestors didn’t bother fixing them. Even if they wanted to, in many cases it would not have been possible, and in others it would not have been worth the effort.

Only once our species could do something, fairly easily, did we begin to have a problem.

This is particularly true for what I call “satisfaction holes,” or temptations to satisfaction that cannot be fulfilled. Hand-washing is a prime example. Everything has germs, but germs are invisible. So anytime someone touches something, an opportunity for germ anxiety arises, as does the opportunity for soothing that anxiety via an easy compulsion. But the anxiety can never be eradicated completely because a) germs cannot be seen and b) the person will soon touch something else. It is easy to understand, then, how a person can get stuck in this loop—how they can continue to run on the wheel and not go anywhere.

I think this is true for pretty much everything. A hedge—or a haircut—can always be straighter. But presumably there’s a threshold of hedge straightness that even the most OCD person hits. It’s much harder when you’re dealing with something invisible and ubiquitous.

Satisfaction holes are tragic, but the much more common problem is that, as I said above, the modern world provides so much grist for our OCD mills. For example, here’s a description of OCD from the John Hopkins website, with my comments (in parentheses):

What are the symptoms of OCD?

Obsessions are unfounded thoughts, fears, or worries. They happen often and cause great anxiety. Reasoning does not help control the obsessions. Common obsessions are:

A strong fixation with dirt or germs (no knowledge of germs until 19th century)

Repeated doubts (for example, about having turned off the stove) (no stoves)

A need to have things in a very specific order (what things?)

Thoughts about violence or hurting someone

Spending long periods of time touching things or counting (counting what?)

Fixation with order or symmetry (not in the wild, you don’t)

Persistent thoughts of awful sexual acts

Troubled by thoughts that are against personal religious beliefs

Compulsions are repetitive, ritualized acts. They are meant to reduce anxiety caused by the obsession(s). Examples are:

Repeated hand-washing (often 100+ times a day) (no soap or knowledge of germs)

Checking and rechecking to make sure that a door is locked or that the oven is turned off for example (no doors, no ovens that can be turned on/off)

Following rigid rules of order, such as, putting on clothes in the same order each day, or alphabetizing the spices, and getting upset if the order becomes disrupted (no clothes, no spice racks, and maybe no alphabet)

See what I mean? Ironically, because of how much we’ve renovated this world of ours—by all indications, largely to our benefit—we’re frequently left dissatisfied. Frustrated. Compelled, or rather compulsed, to slight improvement. To eternal tinkering.

Could there have been substitutes in ancestral environments? Of course. Checking the flap of the hut, arranging stones just so, counting arrows.5 But not nearly as many. And the consequences, too, were much less severe. A burned hut takes a few hours to rebuild; my house would take a few years. So it makes sense for me to check my oven more often than Reed checks his fire-pit.

Conclusion—or, A Satisfying Close

Evolutionary mismatch has plenty of unforeseen consequences. As Heather Heying and Brett Weinstein write in A Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century, “The benefits [of technological progress] are obvious, but the hazards aren’t.”6

Nobody could have seen this one coming. But, as we’ve remade the world according to our desires, we’ve ironically created more opportunity for dissatisfaction and satisfaction, a one-two punch that has many people—even at subclinical levels—wasting their time trying to make everything just-so.

Finally, what about the fact that women have higher prevalence of OCD? It might be—although I have little confidence in this theory—related to what Rob and I argued in Household Conflicts. If women, by and large, spent more of their time around the human-made part of the world—hut, camp, garden—and men around the non-human made, then it makes sense that women would have evolved a stronger preference for “completeness aesthetics,” and would thus be more prone to its dark side.

In any case, a main takeaway of this article is that humans exacerbated—and in some cases, created—various forms of misery as a result of what they wanted and did. Humans have “chosen” themselves into much of their current misery—including, perhaps, obsessive-compulsiveness.

Of course, without knowing that such modifications were possible, our prehistoric person would not have thought of them at all. This dynamic—only seeing a problem once a solution exists—is something I’ll address more comprehensively in a future article.

For a classic Darwinian take on the evolution of aesthetic preferences, see here. One example of such ideas at work is that humans prefer symmetry because it’s an index of being free from parasites and developmental insults. So, we like a symmetrical face because it’s a sign of robust health.

Rob makes a similar point in his article on boredom. Things aren’t boring in and of themselves, but rather in comparison to available alternatives. Reading is more enjoyable on a rainy Sunday afternoon because there’s not much else to do.

Incidentally, this might lead to less household conflict in an apartment because people are less invested.

There have always been opportunities for violence or transgressive sexuality, of course, which represent a significant share of obsessions in people with OCD. So that hasn’t changed at all, although again, the ammunition for such thoughts might have increased—e.g., seeing a police officer with a gun and having the obsession that you’ll take the gun and kill someone with it. No guns in ancestral environments.

p. 98

I don't know of any evidence the OCD is more common in modern cultures.

For me it took evaluating about 100 patients with the syndrome before I felt I had a feel for it. It is one of the few disorders that I think will eventually be traced to specific brain abnormalities. I base this opinion on the ability of certain antipsychotics to induce the syndrome and ongoing neuroscience research. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/hbm.24972

Thank you.Now I don't have to feel guilty about my messy house.