Thuggistry

Skepticism, Gullibility, and Bayesianism.

There’s a joke about academic degrees that goes like this:

BA: I know everything.

MA: I don’t know anything.

PhD: Nobody knows anything.

As someone who is wildly over-educated, I see not a small amount of truth in this. True, you can’t build a rocket that actually gets into orbit without knowing at least a little something about physics. So the engineering PhD must know something. But my general sense is that in fields in which things don’t blow up when you’re wrong—looking at you, social sciences—nobody knows anything. The so-called replication crisis, the finding that vast amounts of research results don’t replicate, surprised me not even a little bit. I was mildly surprised that this problem extended into “harder” science fields, including medicine, but not much.

This post is about how to figure out what to believe.

Philosophers have a word for this issue, epistemology, the study of how to figure out what is true. My experience as a scientist made me, epistemologically, quite skeptical. I was in a meeting some time ago with people in Philadelphia city government and someone said that such and such must be the case because they saw the finding in a peer-reviewed journal. I regret how hard I laughed because it was otherwise a pretty somber meeting.

From an evolutionary perspective, figuring out what to believe is actually a tough problem. Humans need to learn from others, so they have to believe at least some of what others say, but they also don’t want to believe just anything.

I wrote about this problem in one of my favorite but largely unread pieces. In it, I compare the views of two of my academic heroes, anthropologists Rob Boyd and Dan Sperber. Both study culture, though they take different approaches. Simplifying, Rob thinks people are gullible and Dan thinks people are skeptical. The truth of the matter is of course somewhere in between. Here’s a quick summary.

Rob Boyd’s view is that humans need to learn from one another because they can’t figure out through individual learning how to survive and thrive in whatever spot they happen to find themselves. If you drop an adult into nearly any environment—from desert to rain forest to arctic—they’ll die because they don’t know how to defend and feed themselves in that sort of place. But people do survive and thrive in many different environments because knowledge builds up over time through social learning. Crucially, for social learning to work, you don’t have to know why you soak the corn in lime, why you ferment your cassava, or why you build the kayak into just this shape. You do it because that’s what people told you to do. Rob Boyd puts it this way:

The same learning psychology that provides people with all the other knowledge, institutions, and technologies necessary to survive in the Arctic also has to do for birch bark canoes, reed rafts, dugout canoes, rabbit drives, blow-guns, hxaro exchange, and the myriad marvelous, specialized, environment-specific technology, knowledge, and social institutions that human foragers have culturally evolved.1

The trick is that as a learner, you have to accept that you need to soak your corn without knowing exactly why. You have to be, to some extent, gullible.

As Boyd notes, social learning leads to a vulnerability to manipulation. (The film The Invention of Lying plays with this idea. In a world in which no one lies, you can just accept everything people say as true. If someone suddenly starts lying…) Boyd, again, writes: “The ability to learn from others gives humans access to extremely valuable information about how to adapt to the local environment on the cheap. But, like opening your nostrils to draw breath in a microbe-laden world, imitating others exposes the mind to maladaptive ideas.”

Bad ideas come in many forms.

One striking case of a bad idea that has received both anthropological and popular attention is the so-called cargo cults of Melanesia. In the wake of World War II, islanders observed Allied soldiers erecting airstrips and engaging in seemingly ritualistic behaviors—marching, saluting, lighting signal fires—that were followed by the miraculous arrival of planes filled with valuable goods: canned food, medicine, and weapons. Without the background to understand the causes behind the airdrops of goods, some local populations mimicked the soldiers' behaviors in hopes of attracting their own deliveries of “cargo.” They built wooden air control towers, fashioned helmets from coconut shells, and carved runways in the jungle. Needless to say, this behavior attracted no planes laden with cargo, illustrating one kind of risk of blindly copying the behavior of others without skepticism.

This brings us to an alternative framework, one associated with scientists such as Dan Sperber, Deirdre Wilson, and Hugo Mercier. These scholars resist the notion that humans are cultural sponges. Instead, they argue that people are strategic consumers of information—skeptical by necessity. The issue they point to is that no one, even your parents, has interests identical to your own. Therefore, you have to be skeptical of what they are trying to get you to believe. From this view, our minds are not designed merely to ingest cultural inputs. Instead, we’re designed to vet them. A big part of this is to ask, among other things, who benefits? Social learning is not a simple pipe, bringing ideas from one head to another. Instead, it’s more like a battleground in which interests, credibility, and strategic inference all play a role.2

In the paper I refer to above, I said that one way to think about this was with “domain specific cultural epidemiology,” which shows you that I was in the academic cult long enough to talk like that instead of saying something simple. Today I would just say that how skeptical or gullible you are depends on what you’re learning.

You don’t have to be skeptical when someone tells you the animal over there is called a “cow.” The speaker doesn’t gain by deceiving you about this unless there’s some elaborate practical joke afoot. On the other hand, when the cleric tells you you’ll go to hell if you don’t tithe, well... For some stuff—word meanings, kayaks, and food preparation—go ahead and be gullible. But for the social stuff, which I called “strategic,” be on guard.

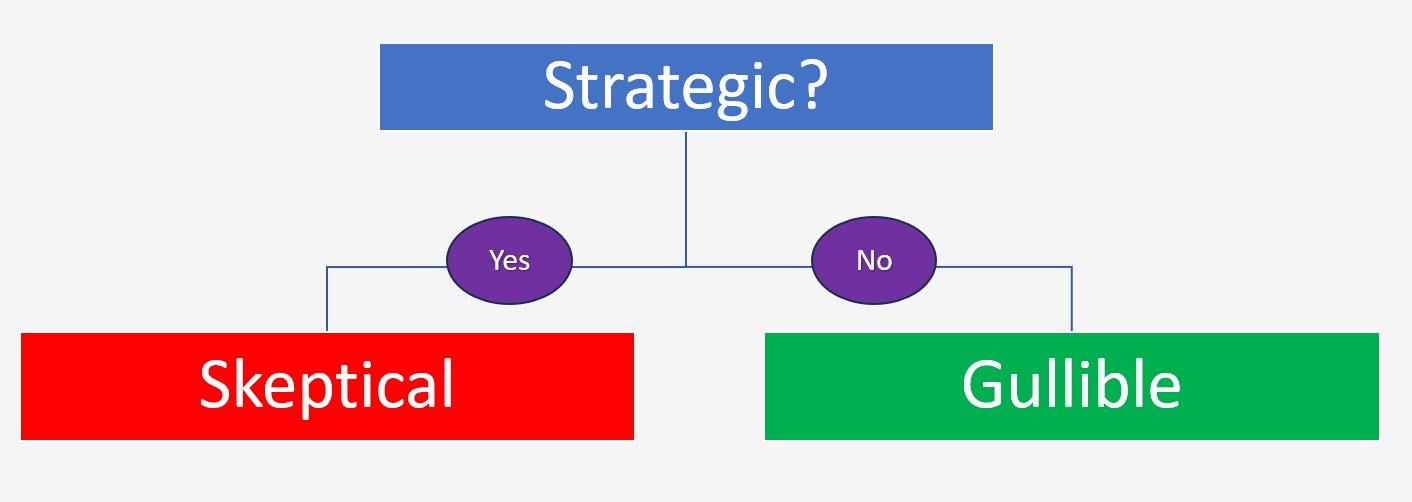

Here is a flowchart capturing this idea as I put it in that paper:

Recently, I have been thinking about that paper and the way it intersects with morality because I think that idea needs a friendly amendment. My concern stems from the observation that in some cases, people hear strategic claims—and should be skeptical—but seem wildly credulous instead. So-and-so killed a man in cold blood. So-and-so stole from widows and orphans. We have always been at war with Oceana. Contrary to the basic flowchart above, some very strategic claims seem to be believed by large numbers of people with no evidence required.

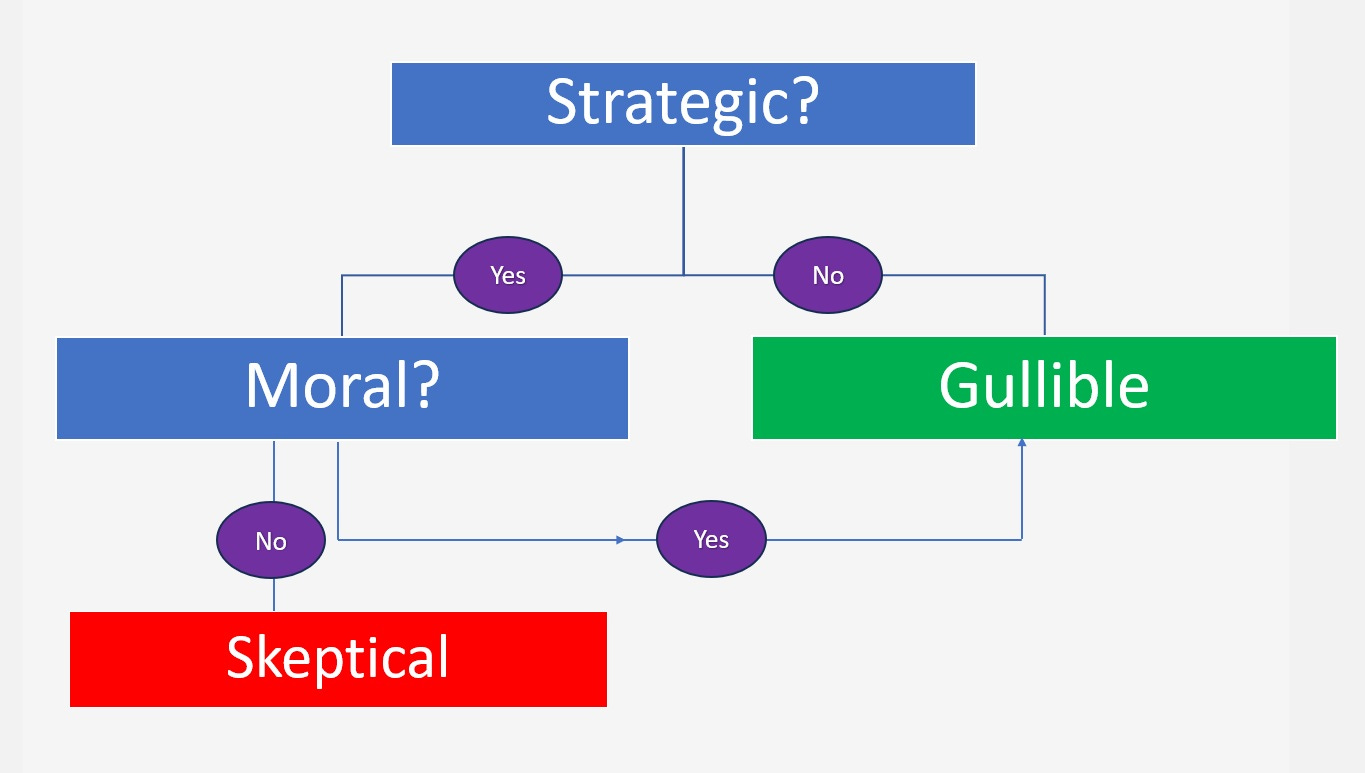

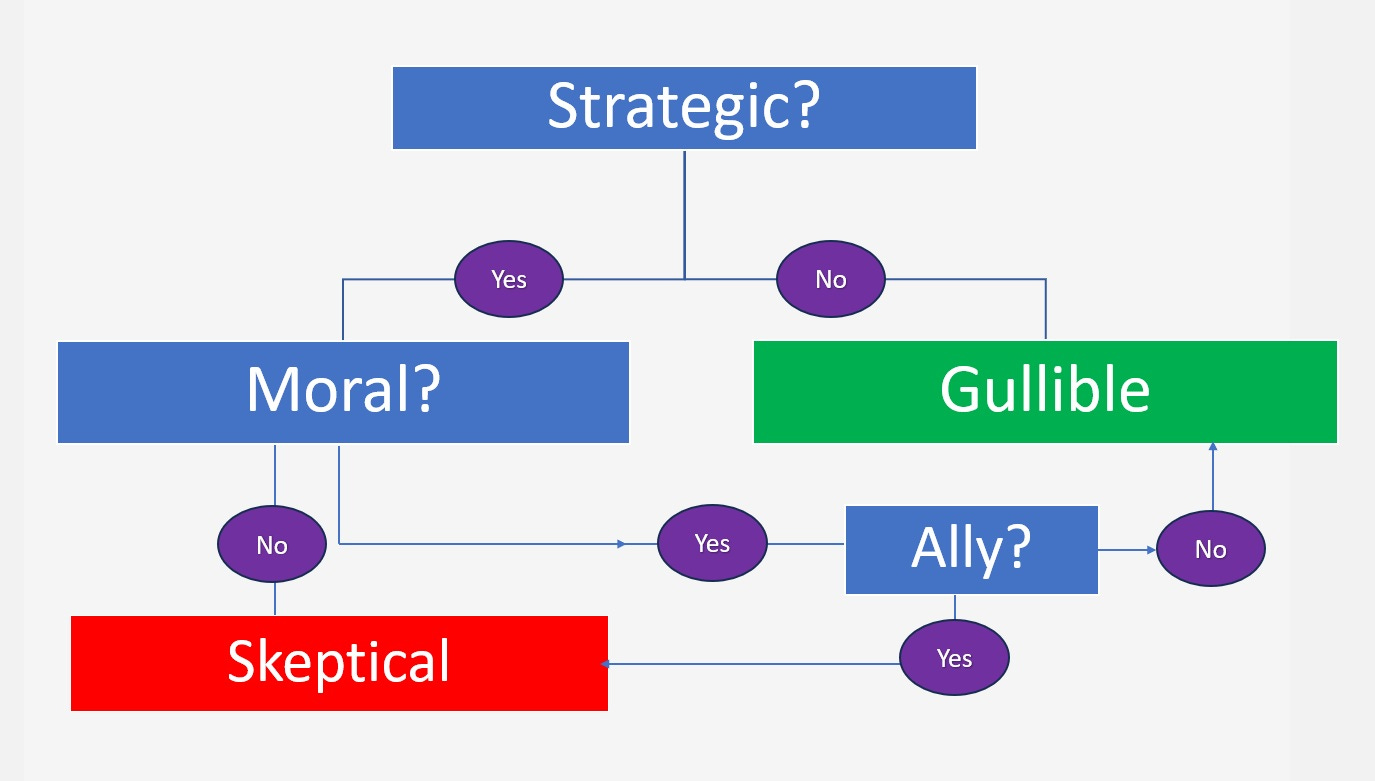

Can we say something about when this is the case? Here is my amended version.

The exception is that some strategic claims are accepted gullibly because they allow people to indulge in a nearly limitless appetite: join in a moralistic attack.

Your everyday experience of life—especially your time on social media—should be enough to convince you that people just love to join moralistic crowds, loudly condemning people who have (allegedly) done wrong. Modern cancel culture is the expression of the same psychology that led people to join in stonings, witch burning, and generally all the mayhem of moralistic aggression.

There is also robust literature in psychology supporting this idea. Molly Crockett has an excellent piece in Nature on the topic. She argues that “[m]oral outrage is a powerful emotion that motivates people to shame and punish wrongdoers” and that this “ancient emotion…is now widespread on digital media and online social networks.” In the behavioral economics literature, evidence suggests that people are willing to bear costs to punish wrongdoers, suggesting that this is an appetite that people will pay to feed, a result that is observed cross-culturally. Evidence from neuroscience suggests that people experience reward when norm violators experience pain. Aldous Huxley perhaps put it best:

The surest way to work up a crusade in favor of some good cause is to promise people they will have a chance of maltreating someone. To be able to destroy with good conscience, to be able to behave badly and call your bad behavior 'righteous indignation' — this is the height of psychological luxury, the most delicious of moral treats.

Suppose you hear that Fred killed a man. Because killing is wrong, you are tempted to believe this with scant evidence because it’s fun to join accusations. Skepticism would get in the way of the joy.

So, an exception to the idea that we are skeptical of strategic claims is that we suspend our skepticism if the strategic claim allows us to indulge our craving to judge and condemn.

Adding some complexity, that exception itself has an exception. If you like the person or group in question being accused then - poof! - your skepticism returns.

You say Fred stole candy from a baby? Burn him! You say my good friend John grabbed a Snickers without paying? Well, do you have the evidence? High resolution video or it didn’t happen.

I think this accounts for a tremendous amount of people’s decisions in this respect, but I don’t know of any good data to back it up, so I’ll just rely on anecdotes.

To a first approximation, I can probably guess a fair bit about your political attitudes by the way that you react—with skepticism or gullibly—to many of the claims below. (I’m not concerned here with which of these claims, if any, are true. My point is about who believed which ones.)

COVID-19 leaked from a Chinese lab in Wuhan.

Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction.

Requirements to wear masks and close schools saved millions of lives.

The 2020 election was stolen

Neil Gorsuch raped a women when he was 19.

Hydroxychloroquine cures COVID.

There are only five polar bears left.

Humans have had no meaningful effects on the planet’s climate.

Michael Brown had his hands up and said “Don’t shoot” when killed by police.

Immigrants are committing violent crimes in the U.S. far out of proportion to their numbers.

The safety and effectiveness of puberty blockers and hormone therapy for minors is settled science.

The only crime committed on January 6th was trespassing.

Ten queries to ChatGPT use two liters of water.

Tax cuts for the rich trickle down to the poor.

Hunter Biden’s laptop was a Russian misinformation campaign.

Obviously, the claims that could populate such a list are legion.

The targets of the attack might be diffuse, as in the ecological examples, but the pattern holds. People believe the claims that charge people they don’t know and, especially, their enemies, with nefarious behavior.

In some ways, this is all dull. Partisans gonna partisan.

Still, it’s worth saying why this flowchart should not be your epistemology.

First, and foremost, it’s just a terrible way to decide what is true. What makes something true or not is something in the world, not the ammunition it provides for moral attacks.

Second, this style of reasoning intersects with the confirmation bias, making it more powerful. Because people seek information that confirms what they already believe, this pattern of deciding what’s true makes it hard to dislodge the false beliefs once they get in your head.

Third and related, people pay much more attention to the initial attack than to subsequent exculpatory information.

The literature in psychology—yes, I see the irony of leaning on the literature, whose fallibility I used to animate this post—is replete with support for these ideas.

Very generally, people tend3 to pay attention to and remember negative information more than positive information or the subsequent correctives to the prior negative claim.

Related, all the way back in the 50s, researchers studying how jurors make decisions found primacy effects: early information in a trial, such as the prosecution’s accusation, carries more weight than later information, such as the defense’s rebuttals. Subsequent work showed the confirmation bias exists in the context of jury decision-making.

More generally, when people are told that prior information they received was incorrect and should be ignored, not only do people continue to take the incorrect information into account, corrections can actually backfire, increasing the weight people place on the false information.

I could point to limitless examples, but I was recently struck by one front in the information war. On July 24th, The New York Times published a story about the tragic conditions in Gaza, including footage of Mohammed Zakaria al-Mutawaq, an 18-month-old looking emaciated in the shot, evoking the horrors of war and man’s inhumanity to man.

On July 29th, the X account NYTimes Communications posted about a correction to the story.

We have appended an Editors' Note to a story about Mohammed Zakaria al-Mutawaq, a child in Gaza who was diagnosed with severe malnutrition. After publication, The Times learned that he also had pre-existing health problems. Read more below.

That is, the emaciated condition of the child had a cause other than the alleged lack of food getting into Gaza.

The NYTimes Communications account on X has 89,300 followers. The New York Times account on X has 55 million followers. See the story at The Free Press for more. The photo is an accusation, accepted by the Times and its readers gullibly, in line with the flow chart above. Skepticism comes later, in the form of a bare whisper.

Quillette recently published a piece that lays out how the recent conflict lays bare people’s biases in what they will believe. As the author puts it (my bold, for emphasis), while “[d]efenders of Israel instinctively discount the atrocity claims,” others “require no evidence to embrace the familiar and uncomplicated fable of Israeli (or Jewish) evil.” A better fit to the diagram above could not be found.

Mark Twain is quoted as saying, “A lie can travel half way around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.” That seems to capture this incident well.

I’m of course not saying this is unique to the Times. (But see Jonathan Kay’s reporting for another example. On that note, I highly recommend the book The Gray Lady Winked, which challenged my perhaps overly generous, even naive, view of the newspaper.) My point in the flowchart is that this is my view of human psychology, generally, not one publication or one side of the aisle.

Instead, my point is that we humans are eager to attend to, believe, and amplify accusations of wrongdoing. We are also indifferent to subsequent corrections because of the confirmation bias and other biases. These are just facts about human nature. When it comes to epistemology, we are neither gullible nor skeptical, let alone Bayesian, but rather thuggist. We’re all thugs, just waiting for the chance to attack whoever or whatever gets painted with an accusation.

Does knowing this help?

Probably not.

Still, next time you hear or read about a hate crime, war crime, thought crime, or just regular old crime crime, ask yourself what a disinterested, unbiased, purely rational being who only cared about the truth would come to believe and what sort of evidence they would need to be convinced.

And then you will go back to your intuitive thuggistry.

My framing here is an attempt to capture some subtle ideas and a quarter of a century of scholarship. Boyd and his colleagues don’t literally hold that people just absorb what others claim. One way to understand the Boydian approach is to consider what they were arguing against. They wanted to address the framing from behavioral ecology that humans, like other species, come equipped with all the domain-specific systems they need to survive and reproduce.

I would add a friendly amendment to this claim. I’d add the word “alleged.”

Yet more irony here. I’m on the record as being skeptical of certain claims by Baumeister, and here I am citing his work to support my thesis.

During the height of the pandemic one of my best friends announced, rather smugly, that he "believed in science." The implication was that I didn´t. Not believing in science being a capital crime, I protested my innocence, alas, to no avail.

Since then I´ve been keenly sensitive to charges of antiscientific bias. I´m a paid subscriber to a writing Substack and we meet up monthly on Zoom to write sentences together. Some months back, our teacher managed to squeeze in the idea that there´s an "antiscience movement" in the US today. As everyone is no doubt aware, people who complain about antiscience cultural tendencies are never skeptical about vaccines or climate change; antiscience is a strictly right-wing phenomenon.

If I´d been born a wild-haired women in 17th-century New England, I might have been burned at the stake for witchcraft. Then, as now, unconventional ideas are little tolerated. It makes sense: witches have never been known for their scientific acumen.

I'm a bit surprised by how this post evolved as a read through it. As a fan of Boyd I would assume you would he familiar with their cultural evolutionary primer Culture and the Evolutionary Process and subsequent work in that area.

The skeptical aspect you discuss is covered by their direct bias concept. But this bias contends with other biases: frequency, prestige/status, and in-group, etc.

You do acknowledge the in-group bias through your "ally" concept, but miss prestige and frequence bias, which played important roles in how we went from a tribal bands of hunter gatherers to our global civilization over 400 generations.