At any given moment, the environment contains too much information for even the impressive human brain to process. This creates a need for shortcuts—also called heuristics—which allow for “good enough” solutions to the problems we face.

Without heuristics, what could we possibly do in the following horrific scenario?

Our sensory and perceptual systems are essentially heuristics. They pick out and parse, from the near-infinite amount of data in our environments, the stuff that is most likely to be relevant to our safety and success. As Rob mentioned in Challenges and Insults, although the electromagnetic spectrum is vast, “natural selection led to the evolution of sensors—photoreceptors—that allow humans to detect a tiny bit.” Evolving the ability to detect the entire visible spectrum, even if it were possible, would have been overkill.

In a similar vein, all else being equal, humans pay more attention to other humans than to beetles. This is because other humans are far more relevant to our survival and reproduction than beetles. How we process sound is another example. We immediately attend to abrupt, loud noises because in ancestral environments this usually meant a major threat. In other words, we “pick” this out of the environmental data more aggressively than, say, a change in temperature. We also hear about 20 to 100 times faster than we see, in essence “fast-tracking” auditory data.

Long story short: we prioritize information based on the effect it has had on our differential fitness over evolutionary time.

One of psychology’s most noteworthy achievements over the last seventy years—and there haven’t been many of them—has been uncovering how evolved heuristics affect our thinking and decision-making. Scholars once theorized that humans were “rational” creatures that would make optimal decisions as long as they had enough information.1 Then Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman came along and showed how these mental shortcuts can “distort” reality and occasionally (but predictably) lead to suboptimal judgments and decisions. These are called “cognitive distortions” or “cognitive biases.” Most readers will probably be familiar with a few of them, such as the confirmation bias or the sunk-cost fallacy, but the full picture is quite staggering.

What tends to get lost in the cognitive distortion literature is that these heuristics were largely successful in the evolutionary game, and only seem “irrational” or “maladaptive” in certain contexts—for example, modern life.2

In addition to evolved heuristics, people can adopt intentional or conscious ones. For instance, in Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman advises that when it comes to something like travel insurance, people should either always or never purchase it. Both are viable solutions over the course of one’s life, and the nice thing about adopting a policy is that you don’t have to think about it each time. One of my own “rules of thumb” is that I never do anything on Sundays. No matter what is happening, my answer is No. (Eventually, people stop asking. It’s great.)

What does any of this have to do with mental health?

If intentionally adopting a “rule of thumb” helps people make complex decisions faster, like whether to purchase travel insurance, can the same be done for questions regarding our happiness and mental health?

A few years ago, I asked a dozen of my friends the following question: “What five things would you recommend to someone who wanted to be happier?” I received a wide range of answers, from “stop being a little bitch” to “travel,” but the range wasn’t as wide as I would have predicted.3 In fact, it was narrow enough that a simple heuristic emerged. I’m sure there was a little confirmation bias in my finding it, given that it’s exactly what you’d expect from a Living Fossil. Can you guess?

The heuristic is to ask: “What would a hunter-gatherer do?” (WWAHGD?)

From my point of view—as an admittedly biased observer—it is amazing how much of what is peddled as healthy for the individual and society would naturally result from imitating a hunter-gatherer life:

Oh, exercise is helpful for longevity, and should partake of both cardio and strength-training? Our cardio should consist of long periods of low effort, like a slow jog or fast walk, interspersed by quick all-out bursts? Sort of like, I don’t know, a hunt?4

Hm, exercise may be more effective than therapy in reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression? That’s odd.

Does nocturnality come with adverse health effects? Do people sleep better when it is dark and cool, as they did for hundreds of thousands of years?

What was that again? A wide variety of whole, organic foods are good for me? And artificial or processed foods are not? I wonder why that is. In fact, I wonder if there is an explanation for why most artificial things—from noise, light, food, and fertilizer—are bad for me…

Chronic noise exposure is detrimental to my health? From non-natural noise like airplanes, car traffic, and train stations? Huh.

So you’re saying that connection, or a sense of belonging in a group, is the best predictor of health and longevity for one of the most social species on the planet? Well, I’m glad we put our brightest minds on that one. Related, you’re saying that therapy’s success isn’t about the fancy ideas from different schools of thought, but rather how well the client and therapist connect?

Come again?—people benefit from being in or around natural settings? As in, there is less crime in areas with more green space, and people who can see trees out their window experience less anxiety? Could this—well, I don’t want to overstep—but could this have anything to do with the fact that we evolved in such environments? Like in nature and such?5

The list goes on. A hunter-gatherer perspective would support the recent push for unsupervised and unscheduled play for children, the decline of which, according to Peter Gray and Jon Haidt, has been partly responsible for the poor mental health of teens. WWAHGD is also relevant to the debate about how to teach reading, acknowledging that because reading words is a relatively recent innovation, students need explicit instruction in it—in contrast to hearing words, which has been around far longer, and which kids can learn simply by osmosis.6 In short, the WWAHGD perspective wouldn’t solve all our problems, but it would cut through a lot of the noise.

Cautions and Caveats

There are at least two valid objections to WWAHGD as a heuristic. The first is—dude, life is so much better now. You think I want to go back to eating grubs and being eaten by bears? No thanks. The second is—how do I know how hunter-gatherers lived anyway?

For the first complaint, see the Coda. And stay tuned. I’m going to have much more to say on this in future posts.

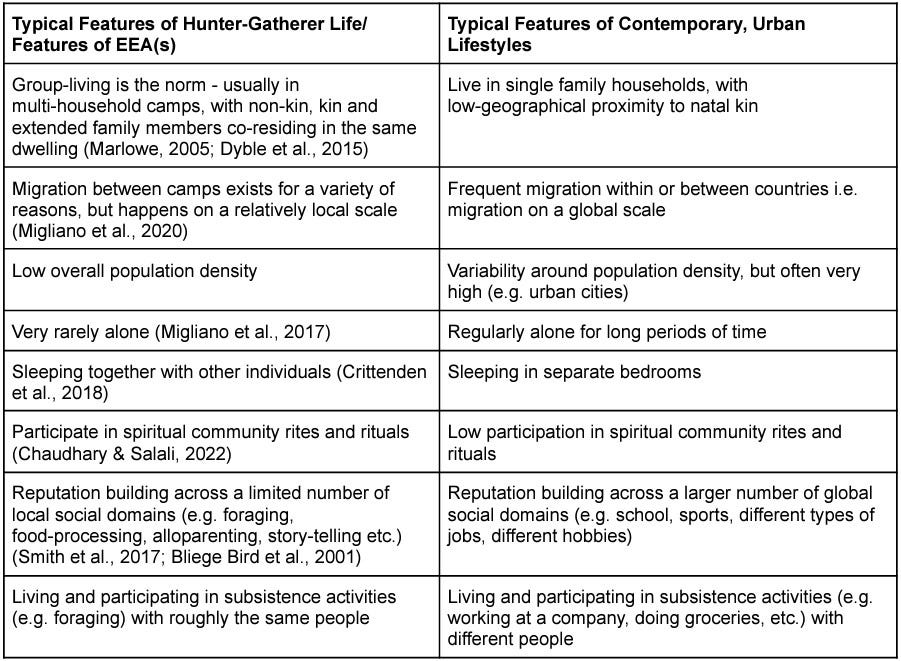

As for the second, I recommend another shortcut. Of course, you are free to do your own research by poring over anthropology texts and maybe even traveling to handful of remaining tribes for some firsthand experience of the hunter-gatherer life. Or, you could simply rely on the following two aids for a “good enough” approximation. The first highlights some major differences between Environments of Evolutionary Adaptiveness (EEAs) and the modern environment:

The second is Brown’s list of Human Universals, i.e. what anthropological studies have revealed in most, if not all, observed human societies.7

If you’re looking for a third way, watch Chimp Empire. Seriously, the show offers an incredible look into human nature through our closest living relative.

By the way, some people might be thinking of a third complaint: that my simple approach to the good life is a post-hoc justification. In other words, I already knew that blue light was bad for people’s sleep, and I conveniently, after the fact, counted it as evidence for an evolutionary-inspired way of living.

This is a common insult in the social sciences. Social scientists have historically been trained to think that explanations for data should come in advance of gathering data. This is visible in the scorn for what some call HARKing, Hypothesizing After the Results Are Known, with some prominent scholars on the record saying that the costs of doing so outweigh the benefits (Kerr, 1998).

This sentiment is not shared across the sciences, though, and it’s easy to see why. Consider—oh, I don’t know—the theory of evolution by natural selection. Darwin gathered a mountain of data before he advanced his theory, looking at evidence ranging from pigeons to finches to peacocks. What was magical about his theory was that it explained so much of the data in a single stroke. Yes, his theory also predicted new observations, but the theory’s victory was in its explanation for what had already been observed.

Explanations are good if they explain—that’s it. If we can organize the long list of what has been found healthy or unhealthy for people by using WWAHGD, then there is legitimate value to it.

Putting It Into Practice

Ok, now that we have a heuristic, let’s put it to use. Say a couple is planning their family. Their first question might be how far apart to space their kids. Relying on WWAHGD, they look it up and discover that HGs generally didn’t have another baby until the last one could walk and keep up with the group. (Carrying one kid while gathering is tough; two is unfair.) So, somewhere between three and five years apart. Amazingly, there are mechanisms in the female body that help with this. When a mother breastfeeds—which she would have done more or less continuously for 3-4 years, until the child could walk and get its own food—she produces a hormone called prolactin, which suppresses ovulation. Voila! Nature’s contraception.

Are there other mechanisms in the body that make a three- to five-year separation between children better for parents and children alike? It’s certainly possible. If a couple is looking for some direction, and don’t have any other strong preferences, why not give it a go?

How about breast-feeding? Our couple might be wondering whether, and for how long, to do so. It wasn’t that long ago that women were being gaslit on this front. The narrative from Big Formula was that breastmilk was deficient, at least compared to formula. That’s not an entirely crazy notion because many things in the modern age are much better than they were in the past (e.g., dental care). But people should have been at least slightly skeptical, given that breastmilk has been fueling healthy mammalian babies for millions of years. That skepticism could have prompted some research, which would have verified the claim as bogus.

Ok, one more. How about risky play? I am constantly watching parents pull their kids away from things that could cause them harm: stairs, sharp objects, feces… A hunter-gatherer perspective could help parents understand when and how to intervene. For some things, like feces, intervene immediately and forcefully. Why? Because there are no learnable skills there, other than: don’t touch feces. But with stairs, railings, slides, sharp objects, and so on, there are skills that kids need to learn, such as how to climb, fall, maintain balance; how to manipulate sharp objects so they don’t cut themselves; and, generally speaking, the lesson that many activities in life are risky if not handled properly.

Again, all a parent must do is reflect on the history of our species, realize that kids have been playing riskily throughout, assume that there is some benefit to that, and allow for some form of risky play in their child’s life.8 The other day, I saw a mom “spot” her kid who was climbing a railing. Much better than pulling him off immediately, no?

A Guiding Principle, Starting Now

There’s a lot of self-help advice out there. I won’t pretend to know half of it. But I’m guessing that much of it is complicated, contradictory, and oversold. WWAHGD is simple, straightforward, and comfortable in its imperfection.

Remember, a heuristic leads to a “good enough” solution at the expense of an entirely correct or perfect one. WWAHGD is no different from other heuristics in that it will occasionally lead people astray. Let’s return to the breastmilk example above. Many medical outlets are quick to point out that while prolactin was a suitable contraceptive in ancestral environments, it doesn’t pass muster anymore for a variety of reasons—primarily, because most mothers don’t breastfeed as continuously as HGs did, meaning that prolactin diminishes between feeds. If people happen to have sex then, well…

Another limitation to WWAHGD is that modern life isn’t going to accommodate much of what it suggests. I’m sure that people would love to work less, be outside more, not stare at so many screens, and sleep for eight hours a night. For a variety of reasons, they may not be able to.

But I have three responses to that. First, people are generally more creative than they give themselves credit for, and can often find a workaround once they know their ultimate goal. Take religion, one of Brown’s universals. Many people can’t bring themselves to believe the content of the religion they were raised in—myself included—much as they might want other things it provides, like as a sense of place, purpose, and community. But there are plenty of workarounds. The WWAHGD framing can help a person recognize spirituality as a vital element both personally and societally. If one version of spirituality isn’t working, don’t throw the entire thing away. Just try another.

Second, even when people lack the ability to live as a hunter-gatherer, the perspective is helpful for setting realistic expectations. If I cannot work less, at least I can understand why I’m so exhausted at the end of the day. (A hunter-gatherer would take one look at our modern workplace and fuck right off.) As we’ve discussed, happiness is a function of reality minus expectations. Thus, the expectations we set matter a great deal.

Finally, a heuristic isn’t meant to be a panacea. It’s only meant to reduce decision-making burden. Across all the various considerations that go into your mental health, and amidst the overwhelming amount of advice and general gaslighting in the self-help space, surely having something that cuts through the fluff is of enormous value? Even if sometimes it only provides a slightly better way?

So the bottom line is this. In every scenario touching on your health and well-being for which you are utterly at a loss, first ask how a hunter-gatherer would have lived. If you can do exactly that, great. If you can get close, great. If you can’t, oh well. At least you have air conditioning:

Coda: When Should I Be a Hunter-Gatherer?

Because a heuristic is a “good enough” solution, there are usually ways to improve it. Given that happiness is, I would imagine, near the top of everyone’s list in terms of what they want from life, it may worthwhile to many readers to follow a more nuanced and specific approach. Enter When should I be a hunter-gatherer? (WSIBAHG?) This perspective, on which a friend has promised to guest-write a post soon, acknowledges that in some areas of life, it’s great to be a modern human. Kids who grow up watching TV really do get a better entertainment experience than their ancestors—other effects aside—and the same goes for modern medicine, food, international travel, sanitation, and so on. Then, of course, there are areas of life in which it is worse to be a modern human. Someone who wanted to optimize their happiness would develop the ability to distinguish between the two. Anyway, I’m personally looking forward to what my friend has to say on this topic.

REFERENCES

Dutton, D. (2009). The art instinct: Beauty, pleasure, & human evolution. Oxford University Press, USA.

Gigerenzer, G. (2004). Fast and frugal heuristics: The tools of bounded rationality. Blackwell handbook of judgment and decision making, 62, 88.

Gigerenzer, G., & Todd, P. M. (1999). Fast and frugal heuristics: The adaptive toolbox. In Simple heuristics that make us smart (pp. 3-34). Oxford University Press.

Mousavi, S., Gigerenzer, G., & Kheirandish, R. (2016). 20 Rethinking Behavioral Economics Through Fast-and-Frugal Heuristics. Routledge handbook of behavioral economics.

Orians, G. H., & Heerwagen, J. H. (1992). Evolved responses to landscapes. In J. H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.), The adapted mind (pp. 555–579). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Todd, P. M., & Gigerenzer, G. (2012). Ecological rationality: Intelligence in the world. OUP USA.

For some excellent work on “ecological rationality” and how effective “fast and frugal” heuristics can be, see Gigerenzer & Todd (1999), Gigerenzer (2004), Mousavi et al. (2016), and especially Todd & Gigerenzer (2012). See also Douglas Kenrick’s work on “deep rationality.”

There were plenty of repeat answers, too. The most common was “maintain perspective.” The strategies for this varied, from writing things down, to experiencing new cultures, to reading. Personally, I never succeed at maintaining perspective—and I doubt anyone else does, either.

See Outlive by Peter Attia, especially chapters 11, 12, and 13: “[H]unting requires 95 percent slow and steady effort, and 5 percent all-out intensity” (Ch. 12).

For early work on human landscape preferences, see Orians and Heerwagen (1992). For a more general treatment of Darwinian aesthetics, see, e.g., Dutton (2009).

Well, not by osmosis. See The Language Instinct by Steve Pinker.

I am really shocked that this is the best version of Brown’s list that I could find. If any readers have a better version, please let me know.

This ought to be even easier nowadays given that many of the ways children died in the past are no longer issues, such as predation, disease, rival clans, and so on. Still, kids need to learn that some modern things such as electrical sockets are dangerous because fear of them isn’t part of babies’ standard equipment.