Athletes Play Coordination Games – Coordination Part III

In 1896, athletes from fourteen nations arrived in Athens, Greece to compete in the first modern Olympic games. Why did they bother?

Who’s the best?

Humans are obsessed with comparison. This isn’t surprising. Humans have to choose friends, mates, partners, and so on. To make good decisions, we have to be curious about others’ relative skills and abilities, comparing people with one another. And, reciprocally, if we are better than others, it’s useful to demonstrate it.

Nowhere is this more evident than when it comes to sports and games. Now, there are many reasons that people play games and participate in sports. For example, I do CrossFit to stay in shape and so that I can talk about CrossFit. But the core reason people gather together for athletic activities is, to a great extent, about comparison. People play games and sports to measure who is best.

In 1896, athletes from fourteen nations arrived in Athens, Greece to compete in the first modern Olympic Games. People could have gathered in Greece to watch people run around willy-nilly, but that wouldn’t allow observers—or the athletes themselves—to determine who was the fastest sprinter, the longest jumper, or the best tennis player. And, indeed, the end result of the Games are medals, symbolizing who is the best, next best, and third best, with medals of gold, silver, and bronze, respectively.

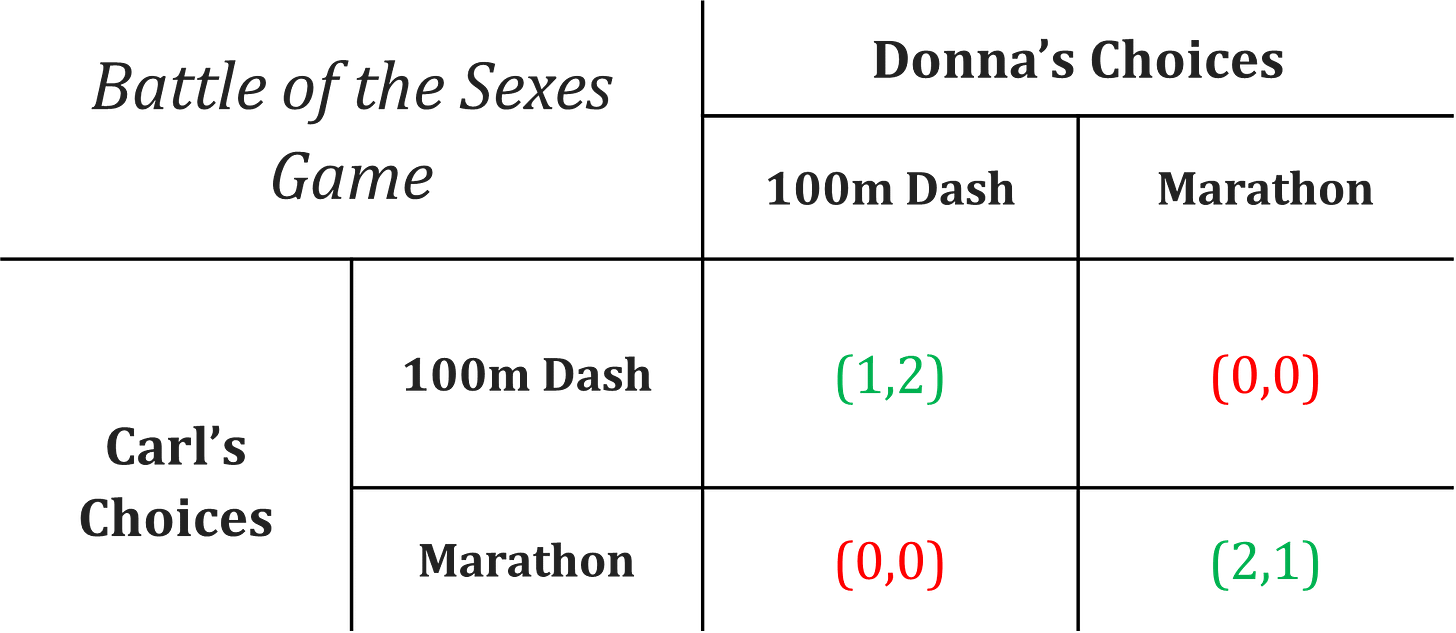

Sports and games can be understood as coordination games. Suppose Donna and Carl, who we met when they wanted to go on a date together, now want to face off in an athletic competition. To measure who is the better athlete, they have to do the same thing. This creates a coordination game because both people want to use the same tool to measure who is better. If they start at the same time but Donna sprints 100 meters while Carl jogs for 1,000, we don’t learn anything when Carl comes in second. So Carl and Donna must coordinate on the rules.

Importantly, the same reasoning applies to all the rules of the game, not just how far one must run. Sports are like double-blind experiments: everything must be the same between conditions so you can know if the treatment was effective. To see this, consider a more complicated case, perhaps doubles tennis, another event in the 1896 games. One can think of different collections of rules about the game—the surface of the court, size restrictions on the rackets, colors of the balls—as different rule baskets. Different players will have different preferences—some do better on clay, some on grass, perhaps—but all want the rules to be binding on everyone so that they can measure who the best player is. The better the coordination on rules, the more reliable the measurement.

There is, of course, tremendous variation in the sports and games people play. Games are designed to measure different skills, abilities, and so on. People want to know who is fastest, strongest, most dexterous, most strategic… And these comparisons are of interest for individuals, couples, and teams. Different sports, with their varied rules, allow these abilities to be interrogated in various combinations. Each newly minted game—Pickleball is a relatively new entrant—measures a new basket of abilities.

In all cases, however, the core question is asking who is better. People’s interest in comparison explains why they seek to measure relative skills. The diversity of domains of comparison, in turn, explains why there are so many sports with so many different rules. If you want to measure speed, you need specified distances and maybe a clock. If you want to measure strength, you need a bunch of weights and rules about how they can be lifted or moved. If you want to measure agility, you might need to invent obstacles, such as hurdles. A similar interest in measuring to compare people with one another explains, for example, standardized tests.

Just as in other cases of coordination problems, different subcultures have different equilibria, or rule sets. Our friends at Wimbledon play on grass, while in the French Open they play on clay. Americans play something called football using (mostly) their hands and an oval-shaped ball, while Europeans play a game they call football with a round ball, largely without using their hands.

In both cases, the rules change over time, adapting to new fan preferences, technologies, and so on. Rules are minted all the time, covering actions as vast as the sorts of things that occur in games that might confer an advantage. Now, to people unfamiliar with a particular game, regulations might appear arbitrary and baroque. Americans find cricket impenetrable, and I’m told American Football can be vexing to Brits. This is to say nothing of the time it takes for us Yanks to master the offside rule in soccer or for non-gamers to figure out Gloomhaven. This variety makes sense once you understand that the rules are solving local—but not global—coordination problems. As long as they are the same for all the players, and all the players know the rules, they can serve their purpose. The fact that rules coordinate players locally, and are free to vary globally, explains their tremendous variety.

Having said that, there are similarities among rules. These represent equilibria that we’ve discussed before. For example, many games and sports use timers, a universal device for measurement. Similarly, sports use very perceptible stimuli—whistles, yellow flags, pistol shots, countdown clocks—to coordinate the activity of the game. These are going to be consistent features of rules. On the other hand, some things will be arbitrary. The exact size of a soccer pitch could have been bigger or smaller—in some sense the specific size is arbitrary—but it was going to have marker lines, just as in other sports. And once the size was specified, fields where people played would be constructed accordingly.

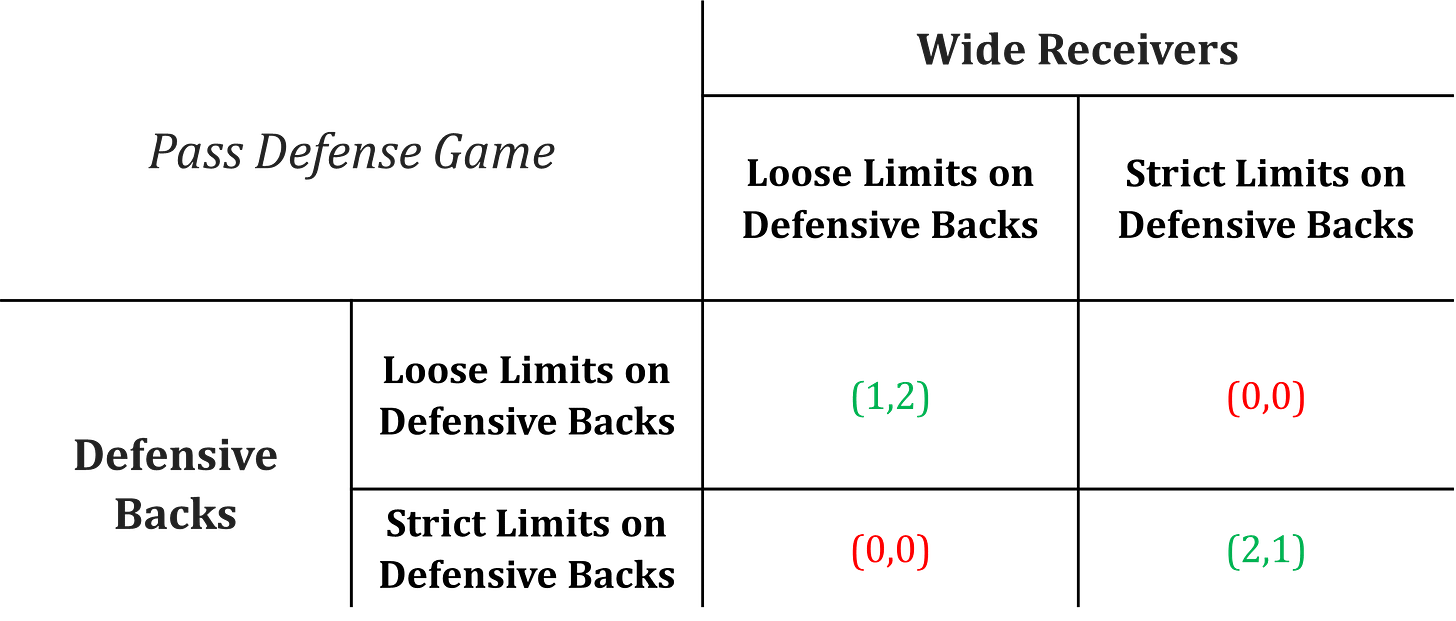

Finally, people debate the rules of various games. My sense is that this debate isn’t as pronounced as we have seen in other areas, but you can find them. If you are, say, the New York Yankees, you don’t like the rule that imposes a salary cap because having a ton of money to hire the best players is a huge advantage. A team in a smaller market favors such caps. At the level of the game itself, conflicts can emerge. In American football, wide receivers—the players who catch the ball—prefer rules that limit the actions of defensive backs, the players who try to prevent catches. And, of course, the reverse is the case.

Let’s review, using the by-now familiar five-point summary of coordination games:

The explanation for why humans have sports is the motivation to measure and compare.

The reason that people want to use specific rules is that they are solving a coordination problem. Everyone benefits from using the same rule system others use to maximize measurement/comparison accuracy.

The reason that different sports use different rules is there are multiple equilibria. You can measure running at many distances and play tennis on different surfaces.

There are similarities among sports, often because there are equilibrium selection forces that result in similar outcomes. Clocks and lines are common because they support good measurement.

There can be ongoing conflict about equilibria, often because different equilibria give an advantage to different players. Which equilibrium is selected has to do with the details of the game and the politics of who decides the rules.

Fouls and Penalties

The coordination game described above is about rules—not rule-breaking. To say that everyone wants a way to coordinate on the same “GO!” signal is not the same as saying everyone, during the game itself, wants to start at the same time. People might well wish for an advantage.1 They might even try to break the rules to get that advantage.

So, once a system of rules is in place, there have to be consequences if a player violates a rule. If no such system is in place—if rules can be violated with impunity—then they can’t fulfill their function.

Because games are designed to measure who is best, the primary (but not only) way in which rules are likely to be violated is in a way that gives an advantage to the violator or the violator’s team.2 To preserve the value of the game as a comparison tool, such violations must be prevented or, if they cannot be, a means must be found to counteract the advantage that was taken.

Take the case of starting before the designated moment, a false start, seen in running events, football, and so forth. Obviously, if one runner begins before others, the race is no longer a good way to measure who is the fastest. Often, the remedy for false starts is simply to have everyone start again (running) or a small loss of something of value (5 yards, in football).

Now, here comes an important twist. Not all fouls are to do with maintaining the integrity of the measurement tool. Sports can be dangerous and, at some point, people began to mint rules to reduce injury.

I asked ChatGPT about the timeline of this change and it, coincidentally, given the framing of this piece, brought up the Olympics:

Ancient Greece: The Olympics in ancient Greece (from 776 BC) had rules and guidelines, but these were focused on fair play and the sanctity of the games rather than athlete safety. However, the importance of training and preparation was emphasized, indirectly contributing to athlete safety.

Ancient Rome: In gladiatorial games, while the primary goal was entertainment, there were occasions where rules were imposed to give some level of protection to the combatants, such as the use of referees in gladiator fights to enforce rules and possibly end a match if a fighter yielded.

Later, innovations such as boxing gloves were introduced, in that case by the Marquess of Queensberry, so the act of punching someone unconscious could be conducted in a slightly safer manner. Indeed, duels probably constitute a similar kind of example. As everyone now knows because of the musical Hamilton, there have historically been precise rules for duels (e.g., walking a certain number of paces before shooting). As people became increasingly concerned about reducing harm, rules were minted to penalize players and teams for the sorts of things that were harmful.

The penalties for violating these rules should be understood as deterrents. They aren’t aimed at restoring balance as in the case of the false start in racing, which literally results in restarting the race.

I cannot stress enough how important the following point is, so I will put it in bold in a box:

So, just because some fouls and penalties are designed to deter harm, that in no way allows you to infer that the whole point of having fouls and penalties is for this purpose. As we’ll see, this has important implications beyond sports.

Fouls and the associated penalties, therefore, roughly come in two functional varieties: restoring the integrity of the measurement and deterring harm.

Because fouls and penalties are designed for these purposes, they mostly—but not entirely—focus on the consequences of the action in question. Most fouls can be easily understood as designed to prevent players from obtaining an advantage beyond what the rules—the coordination point—specifies. Running without dribbling in basketball allows players to travel faster. Having 12 players on the football field gives an advantage in numbers. And so on.

Further, the penalty—the cost imposed on the player or team—tends to be rational in the sense that the penalty tries to just restore the balance of the game or just deter violence enough to prevent most of it. A penalty that over-punished to restore balance would interfere with balance. If a runner, say, who began too soon had to start five seconds after everyone else for a 50-yard dash, they might as well not bother racing. But there’s no equivalent downside for over-deterring violence (aside from scaring people away from playing at all). That’s why penalties for harm tend to be larger, including the possibility of ejection from the game. By and large, penalties tend to be proportional to the advantage one has taken or the harm one is preventing, a point to which we return in a later post.

For many but not all fouls, intentions matter. Some fouls have what one might call strict liability: it’s a foul even if the action wasn’t intended. Occasionally football teams field 12 players—more than is allowed—but even if it’s an accident, it’s still a penalty. False starts are the same. On the other hand, many penalties require intent (e.g., “intentional grounding” in football) or could not occur without intent (e.g., using a piece of prohibited equipment). Related, many penalties are considered more serious—and penalized more—if they are intentional (e.g., roughing versus running into the kicker, in football).

And, as usual, there is disagreement about what fouls should be in place. Different players with different capabilities are going to be helped or hurt by different regimes. This explains why people fight over the rules.

In this game, different players prefer different equilibria. This will have to be settled by whatever process is in place. In the National Football League, there is a Competition Committee that reviews changes, but ultimately it’s settled by a vote of the team owners. Voting is one type of equilibrium selection. (Evolution is another, which we saw in the contexts of cicadas.)

In contrast, some rules are going to be very appealing to pretty much all players. Athletes don’t want to be needlessly harmed, so penalties for violence are common. Anti-violence rules are strong attractors.

Indeed, the father of coordination games himself, Thomas Schelling, used helmets in hockey games to animate one of his classic papers discussing coordination problems.3 Wearing a helmet obviously increases your safety, but it decreases your field of view, which puts you at a disadvantage. Without a rule about helmets, players must choose between being safer and being better at the game, giving braver, helmetless players an edge, at the expense of their safety. Better for everyone is a rule that requires helmets: no one can get a competitive advantage, all are safer, and no fan will think a player cowardly for donning a helmet, since it is required.

Here, players like the helmet rule a lot, though maybe brave players are more ok with the optional rule. The big difference in scores between the two possibilities means there is strong equilibrium selection to land on the requirement. When everyone, more or less, has similar strong preferences, arriving at that equilibrium is relatively easy under many different equilibrium selection processes. In this case, the equilibrium selection is done by vote, and the requirement wins.

Summing up, the explanation for why humans specify penalties and fouls is to ensure that the game retains its ability to measure relative ability and reduce harm.

The reason that people want to have a specified set of actions (fouls) that will be penalized is that they are solving a coordination problem. Everyone benefits from having a system in place to restore the game’s ability to determine a victor. An additional function is to protect athletes’ safety.

The reason that different sports identify different fouls is there are multiple equilibria. There are many different kinds of actions that might provide an advantage, undermining the value of the game in arbitrating who is better.

There are similarities among sports, often because there are equilibrium selection forces that result in similar outcomes. Fouls tend to have to do with actions that confer advantage. Once this system is in place, it can also be used to deter harm.

There can be ongoing conflict about equilibria, often because some equilibria are better than others for some players. Which equilibrium is selected has to do with the content of the rule, the interests of the relevant parties, and the process by which equilibria—rules about penalties—are implemented.

Summary and Conclusion

Sports and games provide, at their core, measurement tools. These only serve their function if they measure everyone in the same way. Good sets of rules allow athletes and teams to be ranked by skill or ability. The need for equal measurement creates a coordination problem: the rules only work if everyone agrees on them in advance, and if everyone follows them during play. Everyone must decide, before the game is played, what rules will be used, and what to do when the rules are broken.4[5]

Most importantly, what rules are for informs what rules are like. Form follows function. Some rules function to restore balance after actions that provide an unfair advantage. The penalty is designed to preserve the integrity of the game as a measurement tool. And some rules function to reduce harm, using reasonable punishments as a deterrent.

In the next post, we arrive at the actual destination of this series on coordination: morality. We will see how, like the rules of sports, the rules of morality are a coordination game.

CODA: Please note. There is a companion to this piece in our new section called The Boneyard. It is likely to be of interest mainly to those who follow the scholarly literature on morality, so we buried it there.

I’m going to avoid the word “fair” in this section. The word has many different meanings so using it potentially leads to ambiguity. My sense is that many readers will think a lot of this section is really about “fairness.” My view is that, in this context, what fairness means is essentially coordinating on the same measurement tool.

I’m going to stop referring to the violator’s team from this point on, for brevity, but the ideas apply both to individual sports and team sports.

Schelling, T. C. (1973). Hockey helmets, concealed weapons, and daylight saving: A study of binary choices with externalities. Journal of Conflict resolution, 17(3), 381-428. See also his book, Micromotives and Macrobehavior.

Josh doesn’t like when I discuss CrossFit. But I just can’t write a piece about sports without at least one footnote. The CrossFit games are, to my mind, an interesting example because players execute the specified workout anywhere, which means that there must be clear rules in place about demonstrating one has executed the workout as specified, with such and such a set of weights in such and such an amount of time. For this reason, people record their workouts to ensure compliance with the rules and CrossFit issues very clear standards for what counts as a rep. For example, a “box jump,” to count, must be at least 24” high and the athlete must stand up at the end. Have a look at the care and detail in the description of the workout here, for instance. It’s an 8-page file to describe how to do 3 wall walks, 12 dumbbell snatches, and 15 box jump overs.

Regarding the point that was so important that it was put in bold in a box: ironically, in the Substack app on my iPhone in dark mode, the box and its contents are almost completely invisible unless the brightness is turned up all the way. 😉

I may switch back to light mode for this reason alone!