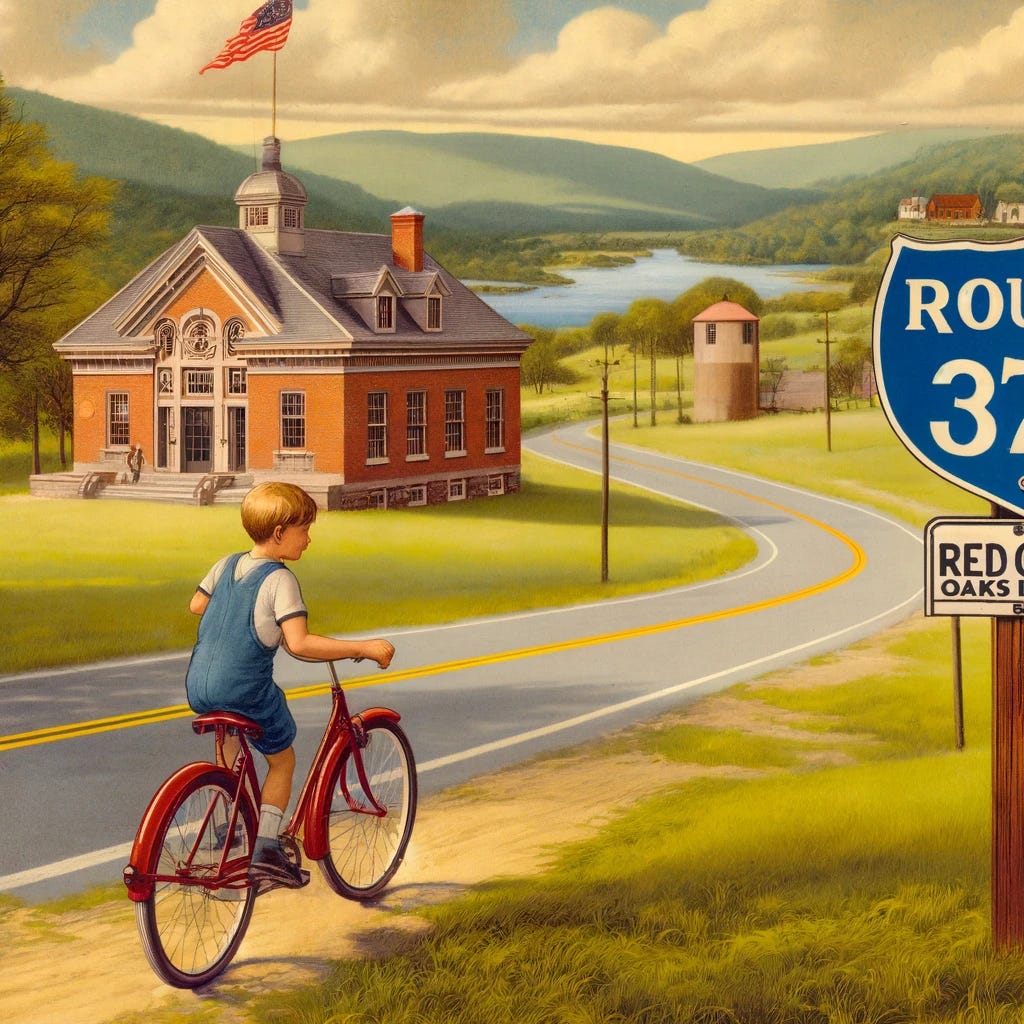

When I was a kid growing up in Poughkeepsie, New York—we called it “the shining star of the mid-Hudson Valley”1—as soon as my (protective, Jewish) mother allowed me to ride my bicycle on Route 376 to Red Oaks Mill, I did so frequently to visit the small public library there. Now, my parents never declined when I asked them to buy a book for me, but this was before Amazon, so to get the new ones, we had to schlep to Waldenbooks at the South Hills Mall. But the Red Oaks Mill library was always there.

In the Science Fiction and Fantasy section, I read stories to my heart’s content. These books were my introduction to authors from Asimov to Zelazny. There were novels set in the Star Trek universe, too. From these works, I learned that, by and large, scientists tended to save the world and/or galaxy. Scientists foiled intergalactic dictators, hatched mind-bending schemes to save humanity from itself, and generally used logic, facts, and hard work to benefit the sentient beings of the universe. The Federation, especially, was wise, fair, principled, and armed with photon torpedoes.

Having come into my just-shy-of-clinical-levels-of-narcissism at a precocious age, I decided during my youth that I too wanted to be a scientist so that I could, ultimately, save the planet, if not the galaxy, and maybe one day fire photon torpedoes in the process.2

But which science? My first crush was on biology. The Panda’s Thumb, by Stephen Jay Gould, came out in 1980, and I recall loving the book, especially the parts I understood. Then there was Sociobiology by E.O. Wilson, which was my introduction to the idea that my first love, evolution, might be relevant to what would become my second, psychology.

Two things sealed the deal. First, it seemed to me that Wilson was linking history—in the form of evolution—to human behavior—the “socio” part of sociobiology—and adding the quantitative promise of biology, which sorta kinda sounded to me like Isaac Asimov’s uber-science in the Foundation series, psychohistory. I definitely wanted to do that.

The second thing sprang from the first. When I was at Cornell, David Buss, who was close enough to a sociobiologist, came to give a talk in the Department of Psychology. Unusually for an undergraduate, I attended the presentation and all I remember is the question-and-answer session that followed it. Specifically, I recall that Professor Sandra Bem stood up and launched into a discussion of how “all the sex differences you explain with biology I can explain with culture.”3 David started to break in, at which Dr. Bem said, “You’ve had your chance, now it’s my turn!”

So that made an impression. A few years after that, I entered a PhD program at what I thought was the second best place to study rebranded sociobiology: the new field of evolutionary psychology.4

Entering the Academy

When I arrived at graduate school, I thought that the way science worked was just as it would if it were done by the relentlessly logical residents of the planet Vulcan. Here, in abstract form, is how I envisioned the conversations I would soon be having:

T’Poe:5 I believe the explanation for phenomenon P is X.

T’Dor: I have facts F1, F2, and F3, all of which undermine explanation X.

T’Poe: Those facts have reduced my confidence in X. I now offer explanation X’.

T’Dor: Let us make additional observations and test to see if there are facts that undermine explanation X’ for phenomenon P. Let us try to refute X’.

T’Poe: That is a logical way to proceed.

T’Dor: Then let us proceed.

It will surprise no readers to learn that this is not, in fact, the way science works, at least in my experience. Let me contrast how things occur at the Vulcan Science Academy with how they actually occur. We journey now to ClownWorld, which T’Poe is visiting to spend time among the resident academics.

T’Poe: I believe the explanation for phenomenon P is X.

Clowny McClownface: You are a horrible person/Vulcan.

T’Poe: Whether that is true or not is subjective. In any case, it is a non-sequitur, irrelevant to whether explanation X is true or not.

Clowny McClownface: I am going to tell my friends and allies that your soul is composed of the purest, blackest evil. I will also call you names.

T’Poe: That intention is also a non-sequitur.

Clowny McClownface: Explanation W for phenomenon P is false because of fact F1.

T’Poe: I will stipulate (but not concede) that fact F1 is true, but that is a non-sequitur because I proposed explanation X, not explanation W.

Clowny McClownface: I have received much fame! Maligning your character and arguing against a position that you did not hold boosted my career and my earnings! I have a book deal!

T’Poe: I wish to return to Vulcan.

Are Soft Sciences Hard?

Imagine that you use a gravitational slingshot around the sun,6 travel back in time, grab someone from Babylonia and ask her which questions below are going to take longer for humanity to answer:

Group A

How did the universe begin?

What are the fundamental forces of nature?

What is the exact, quantitative relationship between matter and energy?

Group B

Why do people read novels?

Why do best friends sometimes fight?

Why do people laugh at jokes?

What prevents corruption?

We’ll never know, but you gotta think she’s going to say the questions in group A are harder. And yet, we’ve basically figured those out. The ones in group B…not so much.

Let me share some of my favorite quotations from the last 75 years of psychology:

[Psychologists] have striven to emulate the quantitative exactness of natural sciences without asking whether their own subject matter is always ripe for such treatment, failing to realize that one does not advance time by moving the hands of the clock. – Solomon Asch, 19527

I think we ought to acknowledge the possibility that there is never going to be a really impressive theory in personality or social psychology. I dislike to think that, but it might just be true. – Paul Meehl, 1978

[I]f mere disproof were enough to rid us of ideas, think of the things we’d be free from: the social sciences, group therapy, raising taxes to decrease government spending. -- P.J. O’Rourke, 1994.

Two features characterize most sciences. First, they are cumulative…But social psychology (like psychology itself) is not cumulative… Second, the scientists of a given discipline agree about the core subject matter... But psychologists and social psychologists do not… -- R B. Zajonc, 1999

Could the pessimism of these worthies have something to do with what Clowny McClownface is up to in the hallowed halls of academe?

I’m not singing a new tune now that I’m out of the business. One of the first pieces I ever wrote, back in 2002, was a review of a book called “Alas Poor Darwin: Arguments Against Evolutionary Psychology,” edited by Steven Rose (a neuroscientist) and Hilary Rose (a sociologist). I recall reading the chapters in the volume—including one by my childhood hero, Stephen Jay Gould—and being fairly shocked at the brazen misrepresentations of the field they were arguing against. Nearly all of it was arguing against W, not X. I’ve linked to the review so you can have a look for yourself, but I’ll just mention two little tidbits.

Hilary Rose quotes psychologist David Barash as saying “If Nature is sexist don’t blame her sons.” I thought that was an odd thing to write, mixing the notion of blame, a moral concept, with Nature, to do with science, so I looked it up and, what to my surprise,8 he never said it. (Barash himself confirmed this.) Thankfully, Rose’s institution investigated the fabricated quotation and disciplined her, after which she apologized to David for putting words in his mouth.9

But the arrow through my heart was reading Gould’s chapter, in which he wrote, “internal error of adaptationism arises from a failure to recognize that even the strictest operation of pure natural selection builds organisms full of nonadaptive parts and behaviors” (p. 123). Now this is a bit technical, but he’s saying that people in my field don’t acknowledge that evolution creates not just useful bits, like eyes, but also bits that aren’t useful, such as your appendix, which just sits there until it gets infected. Anyway, his remark was a critique of the work of people such as John Tooby and Leda Cosmides who, eight years earlier, wrote that “the evolutionary process commonly produces two other outcomes visible in the designs of organisms: (1) concomitants or by-products of adaptations (recently nicknamed “spandrels”; Gould & Lewontin, 1979); and (2) random effects” (p. 62). That is, they advocate for Gould’s view that there are nonadaptive parts and even cite him for the idea.

What in the name of the great gods of Vulcan is the point of this? This is the analog of T’Poe saying “the sun rises in the east” and Clowny McClownface saying, “You dolt! The sun rises in the east!” What is T’Poe supposed to do, assuming he can’t just pack up and head back to Vulcan?

The point is, I was aware of the rot back then. Have a look at Laith Al-Shawaf’s series in Aero for much the same sort of replies to critiques, only twenty years later. Twenty years during which, as far as I can tell, nothing much has changed.10

From Bad to Worse?

Earth science—I mean, science as it is done on Earth—is a contact sport. There are winners, there are losers, not everyone gets to play, and people get hurt.11

Science matters. Sure, some people treat science as a means to clothe their activism in scholarly authority—looking at you SPSP—but history shows that science has tremendously important influences on policy which, in turn, has tangible and crucial effects on people’s lives. To wit…

Trofim Lysenko was a Soviet agronomist whose influence on agriculture in the Soviet Union and subsequently in China had profound and largely detrimental effects on agricultural productivity and food security, exacerbating shortages and famine. His theories, often referred to as Lysenkoism, rejected Mendelian genetics in favor of the idea that environmental conditions could directly alter the heredity of plants and animals. However, he had the backing of Stalin, who favored the ideas in part because of their resonance with Marxist ideology. Lysenkoism promised the malleability of nature and the environment's primacy over genetics, mirroring the Marxist view of human society and the possibility of creating a new socialist human through the correct environmental conditions. Importantly, in both the U.S.S.R and China, dissent from the ideas—the Party line—was suppressed.

And of course this isn’t the only historical example. The eugenics of the Nazis is another. (Biology couldn’t be subverted by ideology today though, right?)

Can we do (social) science without the politics?

In my mind, Vulcans are what are sometimes called these days “decouplers.” To decouple is to consider a claim without any consideration of its political implications or moral weight. It’s just the idea that ideas can be interrogated in and of themselves.

T’Poe: I have evidence that on average—adding some controls—smuggling is more common (per capita) among the Ferengi than among Orions.

T’Dor: Would you please share your controls with me? Perhaps you overlooked a variable to control for.

T’Poe: Yes. That is always a possibility. Here is my dataset. I await your critique.

Clowny McClownface: You are literal Nazis for even asking this question about group differences! You should both be fired! How dare you!?!

T’Dor: Ok. Well. I now have evidence that people on Earth are emotional to the point of irrationality. Earthlings would be aided by learning to decouple.

T’Poe: On that topic, I do not need to see your dataset. It is quite clear.

Being a Helpful Vulcan

To be a Vulcan is to be a product of the Enlightenment: to apply reason, without emotion. The two most difficult aspects of being a Vulcan, I think, are, first, that you have to face dispassionately the possibility that there are going to be some facts that you don’t like. Second, and this is even tougher, you have to face dispassionately the possibility that there are going to be some facts others don’t like.

Scholars, and the systems they have built, are struggling with these problems. People are rejecting some patterns of data because they don’t like what they think will be the implications. Worse, people are attacking other people because they are presenting these patterns of data.

Nothing could be less Vulcan.

Lastly, there is the part about being helpful. Arguing against W when the other person has argued X is not helpful. Name-calling is not helpful. Trying to “win” an argument rather than determine the correct answer is not helpful.

I said I wouldn’t make this personal, but let me add two personal tidbits to end.

I once had the great fortune to work with a brilliant scholar who was, as far as I could tell, as close to the Helpful Vulcan as you could ask. He followed the data where they took him, never injected emotion, and worked together with those around him to discern the truth. I’m not saying he was a Saint, but by the gods he is a great scholar.

He also had Asperger’s Syndrome.12

For my part, I have been told that I have very poor understanding of social cues, a strange obsession with the rules of sports and games, and an overly intense interest in the Trek universe, dating all the way back to my time in the shining star of the mid-Hudson Valley.

You know what I think just might be holding Earthlings back from being Vulcans?

Too much humanity.

CODA

Just as this post was completed, Cory Clark and colleagues published a paper (5/16/24, available open access) reporting the results of surveys asking psychology professors a number of questions to measure the extent to which scholars were censoring themselves, avoiding publishing on topics that are “taboo,” especially those to do with sex and race. I recommend the paper to anyone interested in the topic addressed in this post.

Anthropologist Rebecca Sear took to X (since deleted, but a record of it is here) to weigh in on this paper, writing (her caps, my bold), “New paper argues researchers should NOT consider real world implications of their work, presumably because the freedom to make empirically unfounded statements like women are ruining science with the rubbish brains evolution gave us is more important than preventing mass murder.” The paper by Clark et al., by the way, says (1st paragraph) that the authors “make no claims regarding the accuracy of controversial empirical conclusions, nor do we make claims regarding the optimal norms for policies for science.”

Notice the very Vulcan-like tone of the paper and, in contrast, the less-than-Vulcan-like accusation of sexism and the use of hyperbolic language. Compare Sear’s remark with Clowny’s remark regarding Orions and Ferengi, above. I mean, it’s not exactly the same, but still. My hope is that there will be less of this in the future, as more Vulcan-like norms spread into the social sciences. One can always hope.

We did not, in fact. No one does.

This part of the dream has not come true. So far.

Yes, this was more than 30 years ago. I think I have the quotes here pretty close to right. This was seared into my mind.

This isn’t a dig. I would later come to think it was the top place. My advisors kept a lower profile than some others in the field, hence my confusion. My first choice with to work with Dr. Buss, who was then at the University of Michigan.

My memory is that all the Vulcan names had an apostrophe in them, like T’Pau. I adopt that here as an homage.

Yes, this is another Star Trek reference.

Social psychology, 1952, pp. xiv–xv, cited in Rozin, 2001

I actually was surprised. This was early in my career—I was but a post-doc at Caltech and UCLA at the time, and I was still sufficiently rosy about science that I didn’t think one scholar would just make up a quote by another. Ah, youth…

This is a joke. Of course that didn’t happen. Rose has the right (by academic standards) politics and will always be supported by the academy unless she brings herself to international attention by clumsily testifying before congress after having committed plagiarism, in which case, the “penalty” might be a $900,000 annual salary. Such is the punishment for major misconduct if your politics are right. If your politics are wrong, you can just say something they don’t like to hear and they will come after you.

Ok, that is an exaggeration. Some things have changed. We got Jerry Coyne on our side. That helps.

For an excellent account of the controversy surrounding Gould and E.O. Wilson, read Ullica Segerstrale’s book, Defenders of the Truth. Much of what she says is relevant to the present day.

This information is on the record. He has discussed this in various places. I’m not outing him by any means.

My usual thing -- and I can´t say it´s a good thing -- is to find some small fault with a post and comment on that. In this case, I´m stimied. Pretty brilliant.

Evolutionary and biosocial ideas have more of a hold in sociology now ( particularly in Europe) than they did when I started my graduate career ( 1985). But that is a very slow rate of change! We did not let our kids go into the field, or any social science or humanity ( except economics). One child is an economic theorist and the other is a chemist.