Technology, Part I: Outcomes over Experience

The beginning of a multi-part series on technology. Strap in.

When I started my career as a therapist, I assumed that most client problems would be unique to the client, but that the theories of psychotherapy would provide a general framework for “working through” them nonetheless. I have since found that most client problems have less to do with personal idiosyncrasies and more to do with the situation in which clients find themselves.1 In other words, the majority of the time I am providing therapy, I am thinking to myself: “Yeah, if I were in this person’s shoes, I would respond/feel the same way.”2 This is why evolutionary psychology, by suggesting the context in which certain emotions are likely to arise—as well as the adaptive function they might have originally served—has been a far better lens for understanding my clients’ reactions than traditional therapeutic orientations like psychoanalysis or cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Evolutionary approaches focus on—and illuminate—our shared human nature. They explain why “nothing that is human is alien to me.” Each person is different, of course, but at base we are all Homo sapiens, which means that we have been subject to the same selective pressures for hundreds of thousands of years. To me, this long evolutionary history better predicts and explains how a person will feel in a given situation than their personality or personal history, which is what psychotherapy tends to focus on. Both perspectives are important, but only one has been neglected.

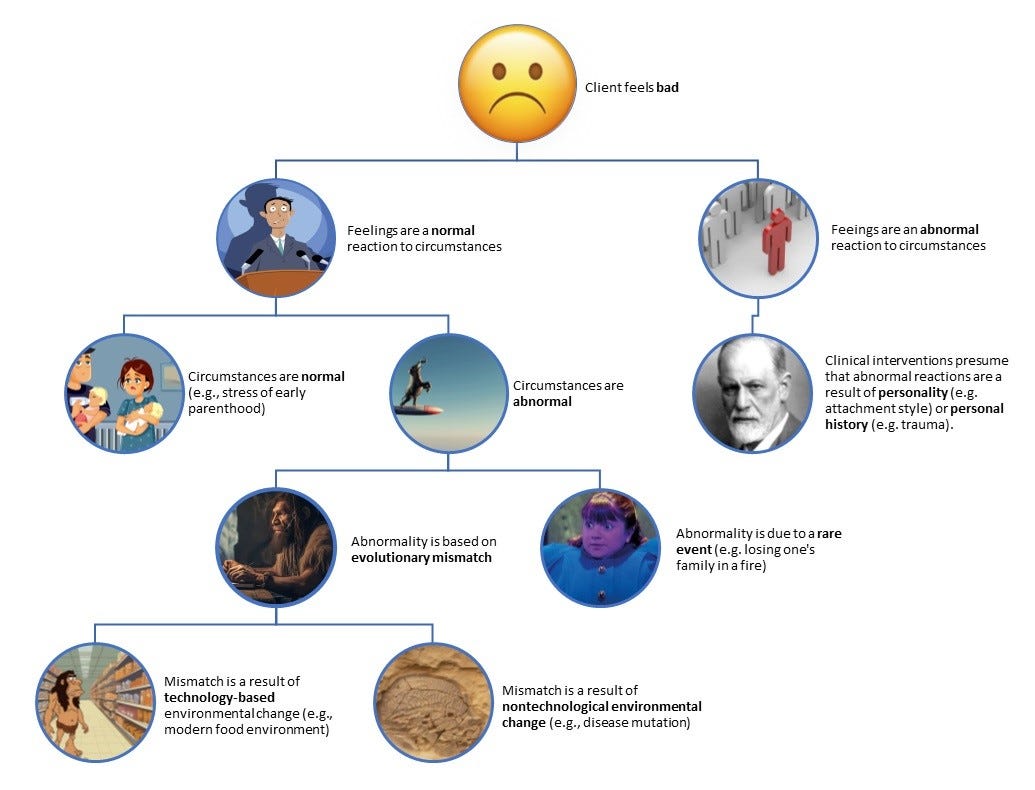

Here is how I have come to see the big picture of where emotional problems originate:3

Consider the first branch in the diagram between normal and abnormal reactions. If a client is having an abnormal reaction to their circumstances, clinical psychology has them covered. In fact, the clinical community tends to presume that the client is responding incorrectly in some way because then psychotherapy (and medication) can provide the most value. This assumption explains why so many therapeutic modalities, from psychoanalysis to cognitive-behavioral therapy, focus on correcting “errors” of client perception—from making the “unconscious conscious” to adjusting maladaptive beliefs—regardless of whether the client is actually misperceiving their situation.4

If therapy acknowledges that the client's reaction to their circumstances is normal, then all it can do is assist the client in changing those circumstances. But even then, the work is done “on the client”—by bolstering their resilience, improving their ability to communicate, increasing their motivation, helping them to see things from a different perspective, and so on—because the client is the only part of the equation a therapist can do anything about. Granted, some therapy, often called “case management” or “social work,” tries to address environmental issues like poverty, unemployment, and domestic abuse directly, mostly by leveraging existing social programs. But this is niche, and not what we usually have in mind when we think of therapy.

Clinical psychology has the least to say, of course, when a client is having a normal reaction to abnormal circumstances. During the covid pandemic, for instance, many therapists just threw up their hands and admitted that times were tough. The best a person could do was try to get through it as gracefully as possible. But because humans weren’t “meant” to be isolated, stay at home, communicate through Zoom, or fear for the world’s end, therapists sort of backed off into a support role and tried to help clients cope as best they could.

My argument is that this is modern life pretty much all the time. We aren’t “meant” to interact with the world around us in most of the ways we do, and therefore therapy is almost always in the position of simply helping clients cope a little better. Therapy can’t solve much—not in the way a medical doctor can set a broken bone or remove a tumor—until it understands the nature of the problems it’s encountering.5 To my mind, the source of psychological distress that best fits the Venn diagram of important and underdiscussed is evolutionary mismatch. In all sorts of ways, humans are suffering because the world around them is, to varying degrees, foreign to the brain that is processing it.

Throw in the fact that technology is the most powerful force creating evolutionary mismatch, and you have your answer to the question: “Why the hell is a therapist writing a series on technology?”

As sad as it is to say, clinical psychology has contributed relatively little to the average person’s understanding of their experience, and this is in large part because it has neglected the evolutionary perspective and the concept of mismatch that proceeds naturally from it. For example, there are currently 76 therapeutic orientations listed on Psychology Today, each with its own account of how mental illness occurs, progresses, and is cured. None mention the fact that the human brain evolved by the same process as, well, every biological entity on the planet. Shouldn’t that be every theory’s point of departure?

No, apparently riding horses and playing in sandboxes cuts more to the chase.

Granted, the brain is the most complicated thing humans have ever encountered. As Anne Harrington (2019) says:

...current brain science still has little understanding of the biological foundations of many—indeed most—everyday mental activities. This being the case, how could current psychiatry possibly expect to have a mature understanding of how such activities become disordered—and may possibly be reordered?6

In the face of such complexity, mental health professionals shouldn’t be adding more. My colleagues and I should instead return to the basics. What do we know for certain? I am happy to keep providing my clients with what care, empathy, and value I can muster from the available state of knowledge, but I also want clinical psychology to start barking up the right tree so that therapists of a hundred years from now can do better. So that societies a hundred years from now can do better. Improvement starts with taking evolutionary mismatch, as well as the process of technology that’s spreading it, seriously. Specifically, we need to ask:

What insights can evolutionary mismatch bring to our understanding of human experience?

If technology creates evolutionary mismatch, why do we keep creating more technology? Why does technology perpetuate itself?

Can technology be done better? In other words, if we find that technology is the root cause of many subsequent problems, can it also be the solution?

These are the questions this series of posts will address.

In the Long Run, No Experiential Gain is Made

“Today the world obtains commodities of excellent quality at prices which even the generation preceding this would have deemed incredible. In the commercial world similar causes have produced similar results, and the race is benefited thereby. The poor enjoy what the rich could not before afford. What were the luxuries have become the necessaries of life.” – Andrew Carnegie, The Gospel of Wealth, published 1889.

Let’s say I’m a homemaker in the 1950s who has just purchased a washing machine. Over the first few months, I experience a small to moderate boost in happiness because I am better off than both my former self and many of my neighbors, who are still scrubbing by hand (i.e., “scrubs”). Indeed, as Jean Twenge writes in Generations, “A hundred years ago, household tasks like washing and cooking took so much time and effort that much of the population could do little else.”7

Eventually, my improved mood will return to baseline for two reasons. The first is adaptation.8 Adaptation is a phenomenon found across the biological spectrum. Organisms as simple as clams decrease their response to a consistent stimulus. For example, if I fire a shotgun one morning in a clam’s vicinity, its initial reaction might be one of alarm. But if I continue firing a shotgun every morning for the next six months, and nothing else happens, the clam will “learn” that there’s nothing significant about it, and gradually minimize its reaction. The same will happen for the little beep indicating that my wash cycle is finished. I might jump out of my shoes the first time I hear it, and a little less each time after that.9

Applied to wealth or material goods, adaptation it is sometimes called “the hedonic treadmill.” The idea is that no matter how much changes in our lives (for better or worse), we’re destined to return to a baseline mood that is heavily influenced by genes. There are some important exceptions to this principle—some things really do make us sustainably sadder or happier—but a washing machine isn’t one of them. If it were, then this graph would look different:

As Adam Mastroianni writes:

[I]n 1948, about 20-30% of American households didn’t have a refrigerator, a flush toilet, or even running water. Zero percent of households had a clothes dryer, air conditioning, or a microwave, because they hadn’t been invented yet. We went from pooping in outhouses to pooping in climate-controlled bathrooms while machines do our washing and cook our food, and our response was a collective “whatever!”

Internally, then, adaptation will yuck my initial yum. I’ll get used to having a washing machine and my attention will move elsewhere. The same thing will gradually happen externally: more and more of my neighbors will purchase a washing machine, erasing my superior position. “What were the luxuries have become the necessaries of life.” As Rob explains in The Thief of Joy, because evolutionary success is relative, so are our emotions, which are designed to motivate adaptive action. For many things, we only feel good or bad if we are doing better or worse than our competitors in the genetic game.10 That’s why being the first to acquire a washing machine feels better than being the last, even though in both instances it saves the same amount of drudgery.

All this brings me back to a balmy day in my third year of college. I was melting through an economics class, daydreaming about being literally anywhere else, when my professor said something I didn’t understand and have never forgotten: “In the long run, no economic gain is made.”11 I eventually came to understand what he meant, enough to make the argument that the same thing can be said for technology’s effect on our happiness. In the long run, no experiential gain is made. Everyone will eventually purchase a washing machine, making nobody better off, and adaptation will steal the joy of having one well before then.

In the Short-Run, A Net of Losers

To quote another favorite line of economists, though, “In the long run, we’re all dead.”12 In the short-term, technology creates winners and losers, whether we’re talking about individuals, companies, or countries. My triumph in being on the front edge of washing machine ownership in my small, midwestern, imaginary town is no different in principle from Apple’s developing the iPhone or the Europeans having Guns, Germs, and Steel in their conflicts with Native Americans. These technological advantages translated into short-term wins, after which everyone adjusted, and the once-novel thing ceased to constitute an advantage.

Of course, short-term losses can be of enormous consequence. (The main one being death.) We also know that, psychologically speaking, losses loom larger than gains.13 Humans typically feel worse about losing a dollar than they feel good about winning one. Because of this, the joy of washing machine owners is probably less than the misery of wannabe owners (although I know of no study that has looked into this).

To go further, isn’t the very existence of washing machines what makes hand-washing clothes “drudgery”? Boredom, as Rob explained, measures the current activity against alternatives, making the available alternatives a key part of the equation. Worse than washing clothes by hand is the knowledge that your neighbor isn’t.

So let’s step back for a second. If technology doesn’t result in any long-term experiential gain, and in the short-term creates an environment of winners and losers in which the losers feel worse than the winners feel good, can we really agree with Carnegie that as a result of technological progress, “the race is benefited?” And if we can’t, then why do we put up with it? Why, after seeing countless material improvements have no effect on life satisfaction, do we keep doubling down on technology?

“I” of the Storm

The answer is that “we” don’t put up with it at all. Humans do not always—or even primarily—make collective choices about how to proceed. Instead, parts of the whole—whether individuals in a group, tribes in a territory, or organisms in an ecosystem—act for their own benefit, the externalities of which the larger group often has to suffer (or enjoy). This is ultimately because evolution operates at the level of The Selfish Gene.

Technology offers an incredible advantage to whoever develops it or becomes an early adopter. Take the Comanche, whom S.C. Gwynne (2010) describes as “the greatest light cavalry on earth” in the middle of the 19th century.14 Before the Spanish reintroduced horses to the New World, the Comanche were scratching out a paltry existence in the Rocky Mountains. Then, because they took to the horse better than anyone else, they became one of the more dominant and fearsome tribes on the continent, if not in the history of the world. The horse was pivotal for the Comanche, pretty damn good for their allies, and really bad for their enemies. As Gwynne says:

The agent for [their] astonishing change was the horse. Or, more precisely, what this backward tribe of Stone Age hunters did with the horse, an astonishing piece of transformative technology that has as much of an effect on the Great Plains as steam and electricity had on the rest of civilization.15

Just because a technology is good for one group of people, and helps them win some competition, doesn’t mean it’s bad for everyone else. Often, innovations bring broadly mixed blessings. Amazon, for example, has made buying products easier and less expensive, and has undoubtedly improved the average product by providing a platform for producers and consumers to communicate. It has also blurred the line between want and need, thereby incentivizing people to buy more than they can afford, or more than is good for the planet.

What isn’t debatable, though, is that Amazon has been best for those who were in on the ground floor. And that’s the basic rub. Technology supercharges the inevitable conflict between different parties in a competitive world, causing winners to win (and losers to lose) much harder than otherwise, all while amplifying the externalities—some of which are good, others of which are bad, and most of which are hard to predict or control.

Humans well understand the many faces of conflicting interests: principal-agent problem, tragedy of the commons, prisoner’s dilemma, free-riders, and so on. Such conflicts of interest have presumably occurred since time immemorial. Robert Trivers has shown that even mothers and their babies have slightly misaligned incentives: mothers want to spread their investment over several children, whereas each child wants all the investment to themselves. This sometimes leads siblings to fight, which, especially among human children, is mostly harmless, or at least contained. Technology is like handing these siblings machetes. It just escalates everything.

Again, we need only think back a few hundred years to Native Americans, who after millennia of fighting amongst themselves with rudimentary weapons, were decimated in short order by Europeans. As were the bison that had long sustained dozens of Great Plains tribes:

Humans’ exceptional ability to create technology has exacerbated competition not only with other humans, but indeed every organism whose interests are not perfectly aligned with ours. Similar to the Comanche with the horse, Homo sapiens’ general capacity for technology has been pivotal for us, pretty good for the organisms we brought along with us (e.g., cows, wheat), and really bad for everything else.

The Missing Piece

Evolutionary success being relative—not only within species, but between species—means there is great opportunity in winning. In removing competition from its ancient and natural restraints, technology has allowed for a more intense “race to the bottom” in which many commonalities are sacrificed in order to gain an edge, whether it be the planet’s genetic reservoir, human attention span, or a stable climate.

Indeed, the climate crisis has allowed us to step back from the short-term effects of a single technology, which is usually what grabs our attention, and recognize the long-term effects of technology writ large. As a therapist, I am most interested in another broad impact of technology: evolutionary mismatch. For thousands of years, we humans have been transforming the world into something our brains are having a harder and harder time parsing. We’ve been niche-constructing to the downfall of our subjective experience.

A shorthand for the net result of technology might be that it improves many outcomes, such as lengthened lifespans and shortened travel time, at the cost of the kind of experience our brains were designed to process and make use of. But this may be happening in ways so subtle, and yet pervasive, that we haven’t quite noticed. I explore these ways later in the series, and attempt to show how evolutionary mismatch is a persistent, hidden theme in all our lives.

Before getting there, though, another puzzle needs to be solved. How is it possible that technology hasn’t netted us more leisure, despite allowing us to do everything faster? That’s what we’ll turn to next.

Thanks for reading and stay tuned.

References

Gwynne, S. C. (2010). Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History. Scribner.

Harrington, A. (2019). Mind Fixers: Psychiatry’s Troubled Search for the Biology of Mental Illness. W. W. Norton & Company.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Twenge, J. M. (2023). Generations: The Real Differences Between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers, and Silents―and What They Mean for America’s Future. Atria Books.

Technically, as Rob and I discussed in What To Do About Emotions, problems exist between a person and their environment, but if modern environments are increasingly mismatched, as I will argue, then the environmental part of the equation should get more attention.

In the chart below, “normal” circumstances are those we would have evolved with respect to. Gravity, for example, is a normal feature of every earth-bound organism, many of whom would have problems if they suddenly tried to live without it. In a similar vein, although rare events undoubtedly happened over evolutionary time, they did not happen with enough frequency for natural selection to do anything about it, and are thus “abnormal.” See Rob’s post for more on both points.

See here for my opinion of cognitive-behavioral therapy’s use of “maladaptive” to describe client thoughts and feelings.

If I were in a fancy mood, I would say: “until it understands the etiology of mental illnesses.”

p. 276

p. 5

At Living Fossils, we’ve also used ‘adaptation’ in the sense of design change over time. So, yes, we are using the same word to mean two different things. This is a consequence of how the word came to be used inside and outside biology.

The corollary is responding more to things that have proven dangerous, e.g., the hyper-vigilance often observed after trauma.

There are limits to this, of course. For some things, like getting my arm sawed off, it doesn’t matter how other people are doing.

For those who weren’t in the class with me, the professor was explaining that at equilibrium in a perfectly free market, competition between companies will limit each of them to “normal profits,” i.e., just enough to cover costs. There are no profits beyond that, sometimes called “economic profits” or “super-normal profits.”

Courtesy of John Maynard Keynes, whom I’ll make fun of later.

“Loss aversion refers to the relative strength of two motives: we are driven more strongly to avoid losses than to achieve gains. A reference point is sometimes the status quo, but it can also be a goal in the future: not achieving a goal is a loss, exceeding the goal is a gain.” Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 302-303.

p. 91

p. 28

Hasn't technology given us leisure to read your fascinating posts which I couldn't have done if I were scrubbing the laundry?

This is an interesting article, but your assumption that technology and material standard of living does not lead to increased life satisfaction is clearly incorrect. There is an enormous amount of research on the subject that shows otherwise.

I would recommend that you question your assumptions:

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/does-material-progress-lead-to-happiness

https://ourworldindata.org/happiness-and-life-satisfaction