Is ADHD Real?

Double-clicking into the diagnosis du jour.

Recently I’ve been mulling why more therapists don’t use an evolutionary perspective. I hope Living Fossils has demonstrated that such a perspective would be a huge boon to the field. In addition to being, well, true, evolutionary psychology provides helpful frameworks for thinking through common mental health themes. For example, the purpose of emotions is to measure and motivate. Emotions sometimes misfire on the principle “better safe than sorry.” Adversity can be divided between challenges and insults: the former make us stronger, the latter weaker.

The evolutionary perspective remains on the sidelines, though, and maybe one reason is that it’s hard to put into practice—or, to use one of psychology’s favorite words, operationalize. Evolutionary psychology is strongest at the ultimate level of explanation (why a certain trait exists), but therapists are looking for proximate help (what to do about it). Sometimes this “implementation gap” is so large that people would rather stick with false or incomplete theories that at least “meet them where they are.”

For now, the main value of evolutionary-based psychotherapy would be negative in the sense that it would do away with many unhelpful, untrue ideas—for example, that emotions are “maladaptive,” that mental illness is primarily a result of childhood experience, or that therapists understand how the brain works.1 The evolutionary view wouldn’t replace these mistaken notions or the interventions based on them with anything positively sexy. In the evolutionary toolbox we’d have the following hum-drum alternatives to the status quo: Wait.2 Consider ignoring your emotions. Distract yourself.

Good luck commanding a high hourly rate with that kind of advice.

I tend to think, though, that if all the effort currently spent on proving that cognitive-behavioral therapy is effective for yet-another diagnosis were redirected toward an evolution-based approach, then within a few years we would have a robust, operationalizable set of practices. Right now, the approach mostly lacks imagination and manpower. One day, hopefully, this “implementation gap” will be closed.

Even if this day comes, though, the evolutionary approach won’t solve all our problems. That’s because so many of them are due to evolutionary mismatch. This is a concept we at Living Fossils have leaned on heavily in our explanation of human misery. It’s very simple: humans evolved in environments much different from the current one. Our design hasn’t caught up because evolution is slow. The result is unhappiness (and other bad things).

There are at least four broad solutions to the problem of evolutionary mismatch:

Redesign our world to mimic ancestral conditions (anyone think this is likely?)

Redesign the mind/body to match current conditions (what could go wrong?)

Return to hunter-gatherer days (sign me up!)

Do the best we can with what we have (sigh)

The first three solutions are obviously beyond the pale, although in theory, each could solve the mismatch problem entirely. The only realistic option is the fourth one. It involves changes at both the societal and individual levels. For example, we could begin to design cities, workplaces, and landscapes that resonate with human psychological architecture. On the individual level, we can read Living Fossils articles and implement their wisdom.

If the mental health industry took part in this, and did the best it could with the science currently available, what would it look like exactly? Let’s see if we can close the implementation gap for the diagnosis du jour: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

The Rise of ADHD

Over the past few decades, the diagnosis of ADHD has surged. Here is a colorful graph of its upward trend among American children. It’s also become part of our everyday vocabulary, used to explain a wide spectrum of behavior ranging from persistent problems focusing to being late once in a while. I’d say that about a fifth of my friends and clients make serious reference to having it. In my practice, I get an inside look at how distractibility and impulsivity can ruin lives. People who can’t focus seem to be constantly putting their lives on hold; time expires before it’s experienced.

In terms of how ADHD is caused or cured, there are enough theories to make a person’s head spin. A psychoanalytic interpretation might be that a person is subconsciously distracting themselves from painful psychic material. For example, a newly-divorced woman can’t sit still because she doesn’t want to face the pain of her recent separation. Until she “processes” that pain, she’ll never find peace. Similarly, I once had a client who would always promise me that we’d “get to the real stuff” as soon as his ADHD was under control. After a few years of never getting there, I began to suspect that ADHD was an excuse: he didn’t actually want to dive deeper.3

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) “aims to lessen the inattention and impulsivity caused by ADHD by changing the way a person thinks and reacts.” If that sounds so vague as to be essentially meaningless, then you’re really going to love my upcoming article in which I bash CBT as respectfully as possible. More specifically, CBT focuses on developing coping skills, such as time management techniques, and challenging unhelpful beliefs, such as “I never finish what I start anyway.”

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) emphasizes four main skills: mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness. Here’s an example of a therapist putting DBT to work:

One of my clients couldn’t focus when studying. We talked about being flexible in her thinking, and making some changes in her study routine. Instead of studying for one hour without a break, she studied for 30 minutes, took a 10-minute break, and returned to studying for another 30 minutes. She found that she was able to accomplish a lot more in two shorter time periods.

Cool.

The “chemical imbalance” theory is never far away when discussing the cause of ADHD, so medications like Ritalin and Adderall are usually prescribed alongside therapy—even and especially for kids, never mind that this can create dependency or limit potential. As Shrier argues in Bad Therapy, kids don’t know what they are capable of yet: a key task of childhood is to figure that out.

Distractibility in the Old Days

Ok, enough of the status quo. Let’s turn to our trusty friend, the evolutionary perspective. It offers two valuable insights. The first is that there is probably a spectrum of distractibility4 among people just as with other behavioral traits, such as jealousy, athleticism, intelligence, and conscientiousness.5 The existence of a spectrum suggests the following:

The capacity for distraction may be serving some adaptive function.

As a behavioral trait, distractibility follows the rules of other behavioral traits, meaning its expression is a result of genes interacting with the environment.

The “ideal” amount of distractibility will depend on the environment.

The variation implies that the trait didn’t matter that much for reproductive success.

Right from the start, the evolutionary perspective helps us realize something the status quo misses: the capacity for distraction is likely necessary. Adaptive. Good. To see why, just imagine someone typing away at their novel as a stampede of wildebeests veers in their direction. It’s not very adaptive if they stay engrossed in character development, is it?6 More generally, it is helpful to monitor the value of what we are doing compared to what we could be doing. Distractibility is presumably in the same family as boredom, which measures our current activity against alternatives.

As always, the question comes down to degree. Do we have the right amount of distractibility? Well, doesn’t that depend on the environment? In some environments, the person with a low threshold for moving onto the next thing will outperform someone who sticks with what is in front of them. In another environment, the opposite will be true.

Optimal foraging theory offers a great framework for thinking about this.7 Say you’re a squirrel in a tree, gathering acorns as is your wont. The question arises: at what point should you abandon the current tree for the next? This is an important determination; after all, time is nuts. Evolution would have selected organisms who had a better heuristic for when to move on than others. But here’s the thing: you don’t know what’s in the next tree. For all you know, the tree could be the jackpot of your life—or it could have been picked clean by your rival. Without the luxury of foreknowledge, you have to make a call and hope for the best.

Genetically speaking, a population of squirrels contains a range of foraging strategies because environments over evolutionary time contained a range of abundance. Sometimes, every tree was Chock full o’Nuts, and the distractible squirrels made bank. Other times, when trees were sparse, the highly-focused squirrels won the day. Variability in the environment led to variability in the trait. On the other hand, almost every human is born with two eyes, ears, and legs because any variation (say, one leg or three) can be disastrous.

A squirrel’s “natural instinct” for when to move on is, in my opinion, the same thing we humans call distractibility. We would diagnose squirrels who quickly moved from tree to tree with ADHD. But there are two important differences. First, humans aren’t seeking acorns, but rather information and stimulation. Second, squirrels are still presumably leafing through trees with acorn counts similar to what they’ve always been. Humans, on the other hand, are faced with more information and stimulation than ever. Thus, a relatively low threshold for moving onto the next piece of information, or the next opportunity for stimulation—which for hundreds of thousands of years would have fallen within an adaptive range—is now a problem.

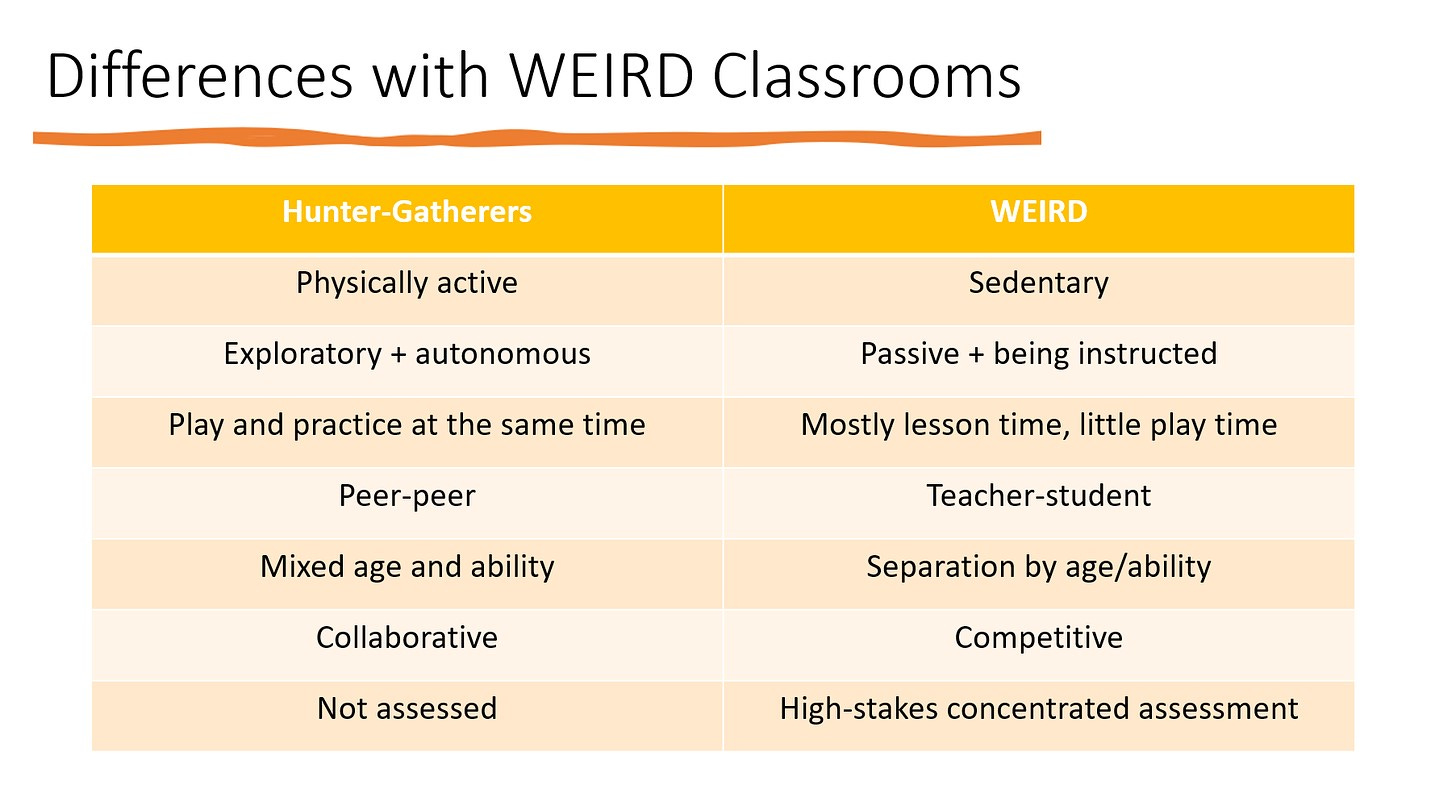

This brings us to the second point our evolutionary perspective provides: the importance of mismatch. Distractibility evolved in environments much different from the current one, meaning we have to understand its adaptive value in the context of those environments, not the present one. For example, the following table highlights differences between hunter-gatherer classrooms and Western, Educated, Individualistic, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) ones:

Are we surprised that kids struggle in WEIRD classrooms? Shouldn’t we expect this, given the environment we are putting them in? Plus, there’s more to it than the table shows. For example, the deliberate time-hacking of our most impressive and advanced engineering. Ditto for our modern diets (hello sugar) and lack of sleep (hello blue light and early school start times). In short, our modern environment relentlessly undermines attention, and it’s doing so at earlier and earlier points in the lifespan.

The modern world is also odd in that people are rewarded for delaying gratification more than ever, which makes not delaying gratification tragically expensive. But remember, the range of distractibility evolved when humans didn’t live nearly as long or have access to investment vehicles like 401(k)s or the stock market. So it used to make more sense to value one marshmallow now over two marshmallows later.

From an evolutionary perspective, then, our modern expectations for focus and attention are absurd. Even though research shows we cannot multi-task, we extol multi-tasking as a virtue and a skill. Even though phones are distraction devices, we allow them in class. Even though hunter-gatherers might not have worked more than around four hours a day, we expect people to work for eight. People are constantly talking about inflation in our economy. How about the inflation of what we expect a human to do in a given day?

To me, the evidence is clear and the logic straightforward. ADHD isn’t a “disorder” of the person as much as it is of the modern world and its expectations. People with ADHD are probaby part of a normal spectrum, living in an abnormal and unfortunate (for them) world. We could even say that the modern world preys on the distractible. The easier it is to grab a piece of someone’s “mindshare,” the better for those who can monetize it.

The Nature of Diagnosis

As an adult, I have a relatively easy time focusing. Despite my computer, I can often work on one of these articles for three or four hours at a time. So why was I diagnosed with ADHD as a kid? Why was I referred to a psychiatrist, who prescribed Ritalin? Fortunately, my parents were skeptical of my diagnosis and reluctant to put me on medication. They decided on a behavioral strategy of more exercise during the day and less sleep at night, which did the trick. (You didn’t have to sell me on watching more late-night hockey!)

I was able to be misdiagnosed, though, because there is no surefire way of confirming that someone has ADHD. Or even, believe it or not, that ADHD is a condition at all.

Some readers might be skeptical. Don’t we have a bunch of smart people, called psychologists, who catalogue disorders of the human brain? Don’t these psychologists create tests to determine who has what?

Well, I’m not so sure about the smart part, but generally speaking, yes. The problem is that mental conditions do not exist in the same way as diabetes or a broken bone, and therefore cannot be tested for in a similar way. Psychologists don’t have the same luxury as other branches of science because the brain is too complicated. We can’t take an MRI and say—aha! There’s your ADHD.

Diabetes is marked by elevated levels of blood glucose, a broken bone shows on an X-ray, and pregnancy is determined by the presence of human chorionic gonadotropin in urine (or a fetus in the uterus). Unmistakable biomarkers like these do not exist for the conditions listed in The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Without biomarkers, psychologists and psychiatrists can never confirm a diagnosis. In fact, my guess is that many of the diagnoses currently listed in the DSM, from ADHD to bipolar disorder to schizophrenia, will eventually be retired or repurposed into something else, when humans finally get a firm grasp on what happens between their ears.8

Psychologists aren’t flying completely blind though. They have developed tests to assess traits such as depressiveness, creativity, and executive function, using powerful techniques in an effort to measure as accurately as possible. For example, psychologists use the same measure multiple times to establish reliability, the extent to which an instrument produces similar results. They try to establish that a measure is valid, or measuring what it is designed to measure, by comparing multiple results from different tests that purport to measure the same trait. They have developed sophisticated statistical tools—psychometrics—to analyze and interpret the results of their measurements.

Despite all this, color me skeptical. The fact that many of these tests are behind a paywall, propping up the psychological testing industry, doesn’t allay my doubts. Then again, if you haven’t figured it out by now, my default assumption is that people know much less than they think, and this only gets worse when they start hanging out in groups. That is why, until we have a hard-and-fast way of testing for various psychological phenomena, I am likely to remain skeptical.

To balance this out, I spoke to a friend who has worked in psychoeducational testing for close to a decade. I asked her whether she thought the center held on all this. She admitted to vacillating between two positions. First, that psychological testing is a helpful intellectual framework that can aid clinical judgment. Second, that it’s a house of cards. She also said that some areas of testing (e.g., neuropsychology) and some tests (e.g., IQ) are much stronger than others that rely on more subjective self-report. More than anything, she emphasized the importance of using a variety of measurements to see if they provided a consistent story. “In the end, it’s a clinical determination,” she told me. No more or less.

Because mental health diagnoses are not built on anything solid, I think they should be taken with a much bigger grain of salt than medical diagnoses. When I get a medical result, I think to myself: Well, the machine or procedure they used could be broken. The office could have mixed up my results with someone else’s. My doctor might be a general-purpose moron. In psychology, though, the difficulties run far deeper. The diagnosis I’m receiving might not be something that is even recognized in 100 years as “a thing.” At the very least, there is no biomarker that my psychologist can cross-check their tests or suspicions against. Hopefully I have a good psychologist who not only administers the test and interprets the results correctly, but also uses multiple data points and isn’t overly hubristic about the validity of the tests in general.

So when the question is asked—“Why the rise in ADHD diagnoses?”—and the answer is—“Because we’re so much better at recognizing it now, and there’s less stigma, too”—I tend to shake my head. That’s not the half of it.

Solutions and Conclusions

There is no doubt, though, that people vary in the dimensions that ADHD tries to measure. So what’s a person to do who is (relatively) highly distractible, inattentive, hyperactive, and/or impulsive?

The evolutionary approach is typically much more straightforward, practical, and realistic than alternatives. Instead of assuming that there is something wrong with the person, it locates the problem between the person and their environment. And it locates the solution there, too. Here are a few solutions that seem like easy pickings to me:

Develop a healthy lifestyle:

Exercise (especially in natural settings)

Sleep more or less, depending

Watch diet (sugar and caffeine in particular)

Meditate (one of the easier ways to reacquaint yourself with slow thinking)9

Reduce or eliminate routine distractions:

no phones in schools; fewer notifications on phone; keep phone silent and hidden if you can; delete time-consuming apps

close out of email, or pause it, for meaningful chunks of time at work

make anything analog that you can (print out recipes, read physical books)

Create focus:

lean into structure and routine (read every day during the same block of time, make the same lunch throughout the week)

prioritize long-form activities (walk with a friend, clean entire apartment)

Lower expectations:

be OK with doing less

Think of this as an equation. Some things add to distractibility, such as too much sugar, poor sleep, and the presence of distractible devices. Others reduce distractibility, such as exercise, long-form activities, structure and routine. More intense solutions, like medication, are available too. But I would stay away from them until I had exhausted simpler options.

As with most states of misery, ADHD is most efficiently addressed proactively. In the midst of a busy day, or overwhelming week, there is no time for creative problem-solving.

Finally, remember that the reason a spectrum of distractibility evolved is that in some situations it will be good, and in others bad. High distractibility or impulsivity isn’t bad in general, just in specific circumstances. The way the environment has changed since hunter-gatherers roamed the earth has been in the direction of rewarding those who have lower distractibility and less impulsivity. But each of us has the power to shape our environment to some extent. For example, travel, socializing in big groups, and certain kinds of jobs might all benefit from higher distractibility and more impulsivity. These traits will obviously interact with other dimensions of personality, e.g. introversion/extroversion, but by themselves will thrive in some situations as they detract in others.

It’s up to you, and your support group, to figure out what those situations are.

REFERENCES

Nesse, R. M. (2019). Good reasons for bad feelings: Insights from the frontier of evolutionary psychiatry. Penguin.

Nobody does, but a functional approach is likely to be much more illuminating than the folk theories that psychotherapy has largely relied upon (e.g., Oedipus complex).

Nesse makes this argument in Good Reasons for Bad Feelings: “Controlling [emotions] is an understandable goal. Scores of books and articles suggest strategies for emotional regulation. Most emphasize changing habits of thought or changing the meaning of the situation. Some try to dampen emotions directly by exercise, distraction, meditation, or psychotropic drugs. Some encourage trying to change the situation despite the costs. Then there is the most common and effective strategy: just wait.” – p. 63

Either that or I had no idea how to fix it.

I’m mostly going to focus on the distractibility/inattention part of ADHD, but the same logic applies to hyperactivity/impulsivity.

You don’t technically need evolutionary psychology for this insight. Behavior genetics would get you here, for example.

I haven’t read it, but apparently The Distracted Mind makes this argument, as well.

And I suspect scientists of the future will come to see what we now call mental illness as a spectra of various mental qualities and capabilities instead, from distractibility to irritability to suggestibility.

Truth be told, I hate meditating, so I’ve found alternatives, like reading or driving. The point is to do something that allows you to think slowly and singularly.

As a teacher I've run into this suspect categorization more than once - most recently yesterday, when I got paperwork informing me that a perfectly capable and apparently normal (temperament, affect, performance) student has ADHD. She's a young teenager who has shown above-average talent in my intro. art class and manifests no unusual behaviors or attributes. My guess is she has a hard time forcing herself to do homework she doesn't like. Maybe by today's enlightened standards that counts as a nascent personality disorder. Of course our counselors and PSW's are all unassailably authoritative, so who am I to question the process? The good thing is I think this girl has a decent chance of outliving the label.

My personal experience with (probably diagnosable, never diagnosed) "ADHD streak" as well as talking to similar people who either never tried or didn't like the medication is that in addition to all the techniques you suggest, the ABSOLUTELY KEY one is to find things to do that you are interested in and that you'd (hyper)focus on without problems. This is hard for many children at school though. I was lucky enough to find most learning interesting and to be bright enough to be able to "work" in bursts of intense activity (this was before the prviledging of regular coursework effort over tests and exams) so the horror of doing boring shit did not hit me well after university, until adulthood, when life circumstances forced me to work for income rather than fun. But the principle of "finding interesting stuff is crucial if you are distractible" stands. I'm a student for fun again at 50+ now and focus isn't anywhere near as much of an issue.