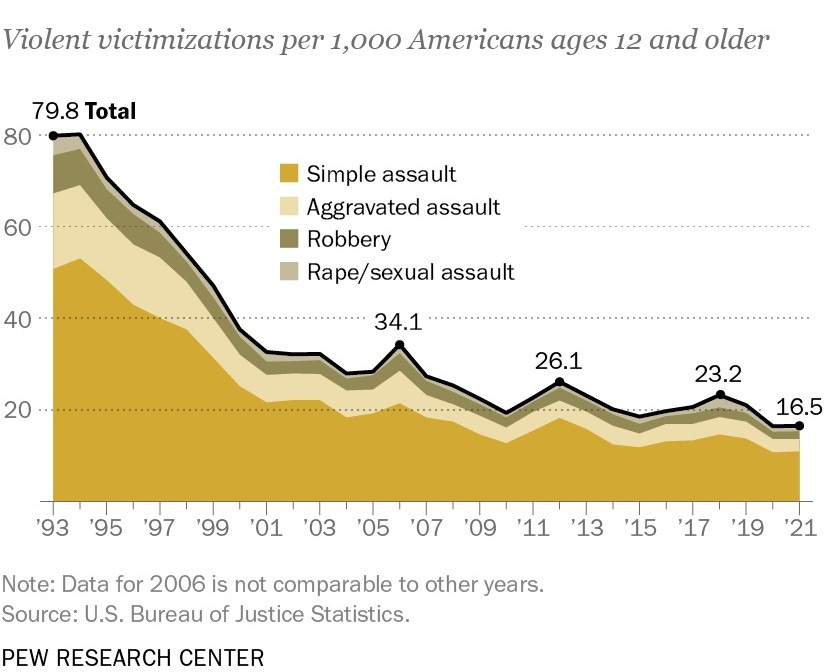

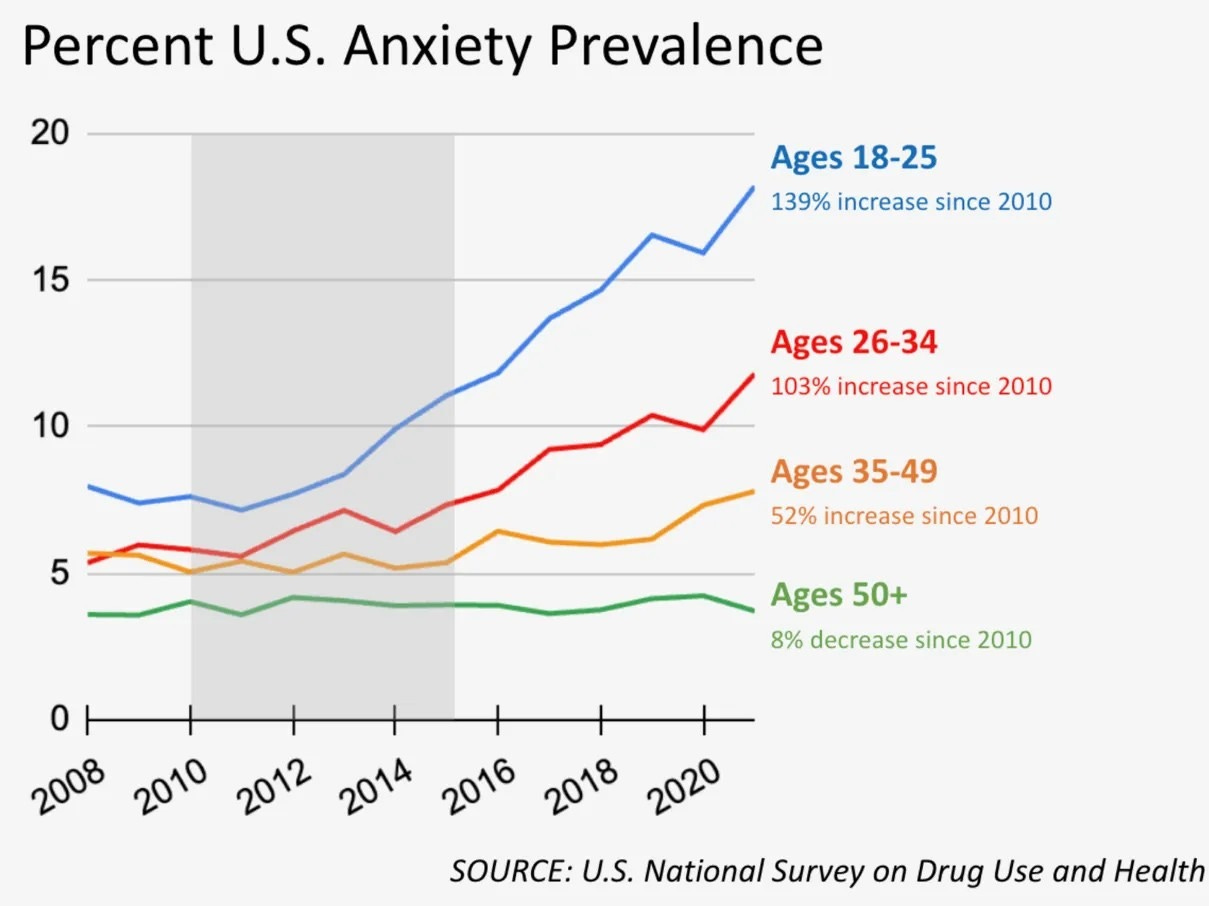

Here’s something odd: Some of the safest people in human history are anxious. In fact, in the United States, anxiety has increased—particularly among young people—as major sources of risk have decreased, from violent crime to fatal car accidents.1

This makes no sense. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, anxiety is “the anticipation of future threat.” As threats of violence, traffic fatalities, infant mortality, theft, infectious disease, kidnappings, and so forth diminish, so should anxiety.2 Instead:

To be fair, threats can be social, too, and life is increasingly unfolding online, where standing can be won and lost overnight. In these curated environments, a constant and insidious threat is that others are doing better than you. Social media platforms also prime negative emotions such as anger, disgust, and anxiety in an effort to keep users engaged, so the more time spent on these platforms, the more those emotions are felt. Finally, there is the difference between reality and perception. The media’s persistent disaster bias makes the world seem much more dangerous than it is. You never hear of the ten thousand hikers who didn’t fall off a cliff.

So, there are many explanations for the prevalence of anxiety among some of history’s safest people. My preferred explanation, though, relies on the mechanism of tolerance. To illustrate, let me revisit a modern parable—the peanut saga.

The Peanut Saga: A Nutty Approach

Most of you have probably heard of the peanut saga by now. The short story is that a few decades ago, a rise in peanut allergies led experts to recommend that children avoid peanuts altogether. This well-meaning strategy backfired: kids who were shielded from early exposure never developed a natural tolerance, and more ended up with peanut allergies than before. Whoops.

Fortunately, the FDA might soon be saving the day with a drug called Palforzia. Its secret? Exposing kids to peanuts:

[Palforzia] seeks to treat peanut-allergy sufferers by exposing them to the very thing that could kill them. Getting the body used to the allergen, by consuming it first in tiny amounts and then in ever-larger portions, can help. Palforzia does this with pharmaceutical-grade peanut protein.3

Vaccines operate on the same principle: the body learns from a low dose of a specific pathogen how to attack it. For all sorts of threats, then, humans need exposure—dosed appropriately—to build resilience. This is a much sounder strategy than avoidance, because as Abigail Shrier notes in Bad Therapy, “Pathogens always worm their way in, even to the most sterilized environments. Better to develop an immune system.”4

It is one of those marvelous facts that strikes a person in spare moments, that the “guess and check” method of natural selection was able to design bodily systems that adjust to environmental demands. The immune system, for example, operates within the bounds of what it encounters, avoiding waste by not preparing for threats it won’t face.5 The downside is that if these systems are exposed to a greater dose than they “expect,” disaster ensues. This explains a wide range of phenomena, from tearing a muscle at the gym to overdosing on a drug. Tolerance must be built in tolerable doses.

Nor is all information relevant. Our bodies are only designed to respond to—learn from—certain kinds of stimuli. In Challenges and Insults, Rob contrasts the difficulty of breathing from exercise—a challenge—with difficulty of breathing smoke—an insult. The respiratory system can become stronger through repeated trials of exercise, but not through repeated trials of inhaling campfires. Smoke is not a piece of environmental stimuli that the lungs can use to improve.6 Rob goes a step further in Insults, Challenges, and Insults, arguing that many modern trials are likely to be insults—for example, noise from constant explosions—because humans don’t have a long history of interacting with them, and therefore haven’t evolved ways of learning from them.

Rob’s two articles provide a framework for thinking through what kinds of trials will be helpful and which will be harmful. When it comes to challenges, we want to build a tolerance—ideally above what we will be asked to do on a daily basis. When it comes to insults, we want to avoid them as much as possible. There’s nothing fruitful to learn.

Living and Learning: Risk as a Teacher

As with the systems of the body, so with the systems of the mind. If we want a robust anxiety system, then we need to expose it to risk in the same way—incrementally—and for the same reason—increased tolerance—that we expose our immune system to peanuts and pathogens. Coddling will only lead to peanut allergies and anxiety disorders.

If the purpose of our anxiety system is to detect threat, how does it know what is threatening? In short, it learns. But it would be very costly to learn everything anew, so there are some shortcuts and workarounds to learning by experience. First, some things throughout our history were more reliably a threat than others, so evolution prepared us to learn them faster. This is why it is much easier to learn—and much harder to unlearn—a fear of snakes than a fear of butterflies.7

Second, other people can tell us something is dangerous—“Look both ways before you cross the street”—or we can absorb what happens to others—“That’s why I’ll never go into business with family.”

The different ways of learning about threats—being told, observing, and experiencing—have their own tradeoffs. Being told involves the least risk of harm but isn’t very memorable, and is also subject to error and deception. You’re much more likely to remember a lesson if you experience the outcome yourself, and the lesson is more likely to be reliable. “Next time, don’t put my hand on the burner, check.” It’s the riskiest, yes, but also the stickiest. Observation falls somewhere in the middle.

As the quote often attributed to Confucius goes: “I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.”

For a person to acquire the opposite of anxiety, then—whether we call that confidence, self-esteem, competence, or composure—they must be able to divide the world into threat and non-threat. Otherwise, everything is a potential threat, and there is no justification for ever letting one’s guard down. Meanwhile, a person will feel most confident about the division itself, between safe and dangerous, when it is based on experience.

Experience has another benefit. In addition to teaching us what is dangerous, it teaches us why. Understanding the mechanism of danger—knowing, for example, the warning signs of a snake before it strikes—helps a person dodge the bite. Knowing how to walk in areas rife with snakes reduces the risk of walking in those areas. Risk’s kryptonite, in other words, is skill. Know-how. A skilled skateboarder goes to the Olympics, but an unskilled one goes to the hospital.

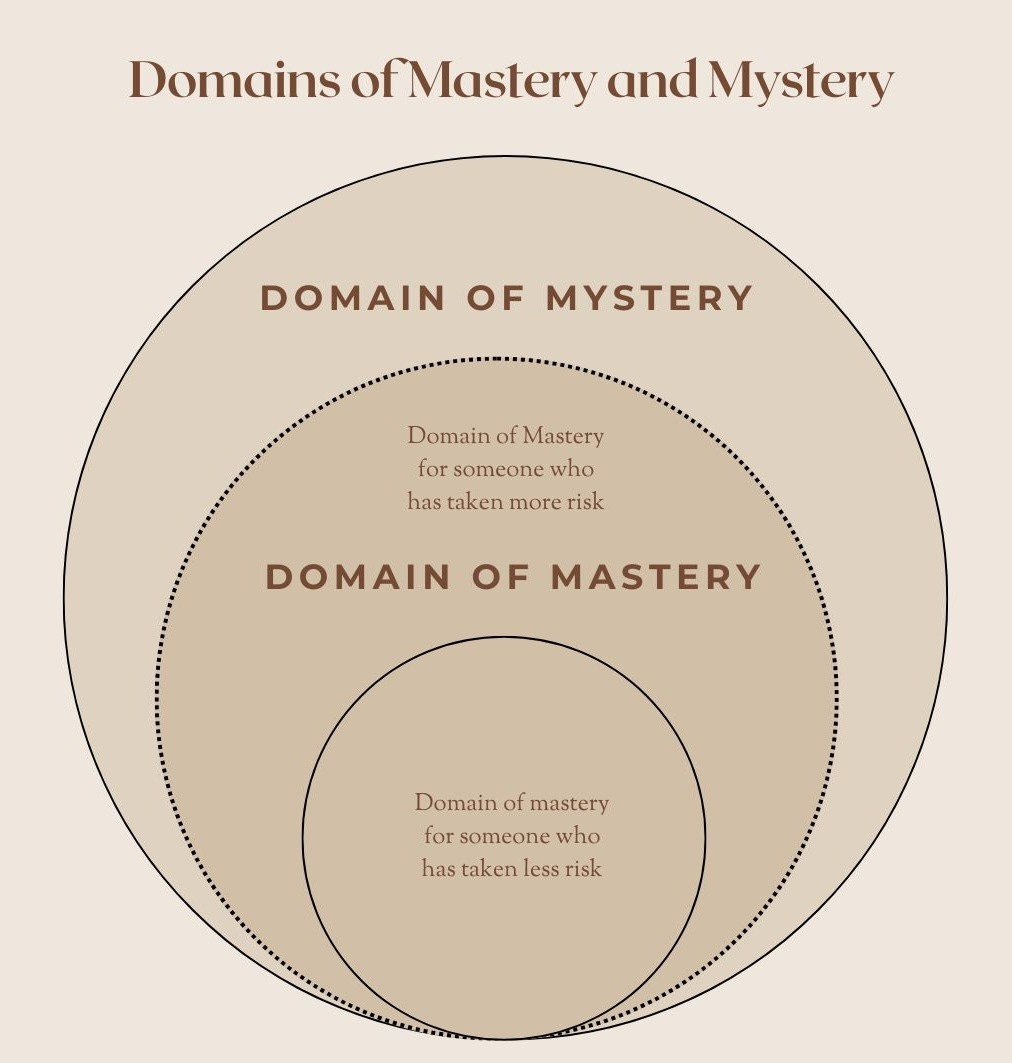

Of course, skilled skateboarders still go to the hospital, and the reason is that they occasionally bite off more than they can chew—just as the novice does, only at a much higher level. But Olympians acquire expertise in the same way anyone masters anything: by consistently pushing boundaries, one manageable step at a time. No-one can observe—or be told—their way to the top. They have to do it. And as soon as the skateboarder conquers one move, anything that is less difficult will seem manageable, even easy. The same is true for anxiety more generally: those who push the risk envelope perceive more of the world as manageable, even safe.8

A final benefit of experience is what I think of as a spillover effect. It’s not only skills that can be transferred from one domain to another—it’s confidence, too. When someone learns how to do a kickflip, they also learn that they can learn. Even if skateboarding and baking don’t share any direct skills, then, a skilled skateboarder can still tackle baking with confidence, trusting their capacity for success more generally. But if a person has been told what to do for most of their life, then when something new comes about, that is what they will rely on. They’ll look around for someone to tell them what to do and how to do it.

Paddling the Pine Barrens

Just a few weeks ago, I went online to find some new paddling routes for my friends and me to explore this summer in the Pine Barrens. On one of the blogs, someone wrote: “Kayaking is great, but I would not recommend paddle boarding as the fin can often get caught on submerged logs/low-water areas. If you do paddle-board, under no circumstances should you stand. You could fall, hit your head on a submerged log, and drown.”

My friends and I have been paddle-boarding the Pine Barrens for years. Not only do we stand, we drink beers while we’re at it.

I’ve come across similar warnings while reading about other semi-risky hobbies of mine, from skiing to backpacking. I don’t know why I spend so much time reading about stuff I already know how to do—I honestly don’t intend to—but at least I’ve learned the valuable lesson that these things sound terrifying even to a seasoned veteran. The authors of these articles, who for the most part strike a balance between the risks and rewards, nevertheless leave me with a sense of foreboding. I’m guessing this feeling is amplified for the reader who hasn’t done the activity, who is probably reading the article to decide whether to do it.

These articles instill fear because of a basic discrepancy: it’s much easier to tell someone what can go wrong than explain how to do something right. So even if the author says of skiing, “Yes, there’s a chance you’ll go flying off a cliff, but a little knee bend and weight transfer can prevent that,” the average reader is likely to be horrified. They can imagine flying off a cliff quite well, but can’t convert “knee bend” or “weight transfer” into the kind of physical understanding that inspires confidence. This discrepancy also explains that common exchange between novice and expert in which the novice asks a bunch of anxiety-based questions and the expert shrugs and responds: “Eh, you’ll figure it out.” The truth is, oftentimes, the novice will. But not until they do it.

Now here’s the funny thing. One of my friends did fall during a Pine Barrens trip and cracked his rib on a submerged log. And guess what? A month later, he was fine. It wasn’t ideal, obviously, but it also wasn’t the end of the world. He was fully healed by our next trip.

The fact of the matter is, paddle-boarding the Pine Barrens isn’t that risky, and only part of the reason is that not much can go wrong. The other part is that a person can do something if it does. Usually, this requires plain common sense—a common physical sense, we might say. For example, my friend didn’t split his head because he held his arm up to protect it…which is precisely how he cracked his rib.

If my friends and I had read a few blogs before heading out for our first paddle, we might have been deterred—and that would have been a shame. On the other side of risk, after all, is reward.

No Risk-it, No Biscuit: Risk’s Reward

The ability to divide the world between threat and nonthreat is best achieved by doing, and knowing where the boundary lies is a skill in its own right. A general rule of thumb is: Whatever is less risky than what has been done safely before should be manageable. Thus, by doing riskier and riskier stuff, at reasonable increments, a person expands their kingdom of confidence.

Indeed, there are two ways to make the world seem safer. One is to actually make it safer. (The modern world has by and large done this.) The other is to learn how to navigate its risks. (The modern person by and large doesn’t do this.)

People don’t develop familiarity with risk in the modern first-world for an understandable reason, though: they don’t have to. As Jean Twenge points out in Generations, it makes sense to reduce the amount of risk we are willing to tolerate as environmental risk decreases. Thus:

With technology making life progressively less physically taxing for each generation, each generation is softer than the one before it…The first humans to use fire probably said to their children, “You have no idea how good you have it…”9

It wouldn’t make sense for today’s children—or adults—to take on the kind of risks our ancestors routinely had to face. But if we recall the peanut saga, it’s not good for people to be risk-free, either. Ideally, people would expose themselves to a level of danger slightly above what is required by their environment.

There is a relationship, in other words, between our bodily systems and the environment in which they operate, and a good policy is to be slightly overprepared. Athletes know this and routinely do in practice what they won’t have to do in a game. Children of dental hygienists, who bring all those nasty germs home, likewise get a leg up.10 When it comes to anxiety, people should strive to take on an amount of risk that is somewhere between stupid and safe, so that most of life seems not only tolerable, but even rewarding.

That said, what if we have reached a point in history at which this amount of risk—between safe and stupid—is still so low that the risk system doesn’t recognize it? What if people can’t even give their anxiety system something to work with without seeming reckless?

In Willa Cather’s My Ántonia, a wonderful novel about a family living in Nebraska at the end of the 19th century, the main character, Jim, kills a man-length rattlesnake when he is 13. (Yes, this scene is fictional, but that sort of thing happened all the time on the frontier. Hell, Comanche children could shoot an arrow from the back of a horse with deadly accuracy by age 10.11) How does Jim feel about his accomplishment? He’s pleased as hell. And his girl is, too: “I never know you was so brave, Jim,” Ántonia admires. “You is just like big mans.”

My favorite part of this story, though, is that Jim’s grandparents (who raised him) had no choice. As modern readers, we gawk and think to ourselves: “He could’ve died!” But what was the alternative—keep Jim indoors for the rest of his life? Wrap him up like the kid in the title image? The insidious luxury of modernity is that we must choose risk now. We must go out of our way to find a rattlesnake. We’d be stupid to take such risks—just as we’ll be sorry we didn’t.

Note, too, that Jim’s grandparents would have been protected from guilt or social blame in the face of tragedy. Had Jim died, no one would wonder, “Was it worth it?” The newspaper wouldn’t be calling it a “pointless tragedy.” Rattlesnakes were a known part of prairie life—so grief, though heavy, came with quieter guilt.

As people live longer, healthier lives, the price of risk will continue to rise—and so will the price of reward.12 I bet there was something nice about having to tolerate a certain amount of risk merely to stay alive, just as parenting was easier when the average family had more children than could be fretted over or doted upon.

Summary of Risk

The solution to anxiety is clear: develop a familiarity with risk. As psychologist David Rosmarin puts it, “The main cause of anxiety is intolerance of uncertainty.” The more uncertainty people face, the more tolerance they build. Exposure, dosed correctly, is the cure.

Risk, danger, challenge—these are the antidotes to anxiety, not therapy, accommodations, or medication.

A cultural shift that acknowledged the benefits of risk would go a long way in encouraging parents to expose their children (and themselves) to more of it. It's not as if the desire to protect ourselves or our kids is new; that’s been around since before humanity. The difference is our current ability to cater to it. Hopefully, books like Bad Therapy and The Anxious Generation will begin to provide the social permission and justification to resist that instinct.

It’s worth noting, though, that resisting instincts and launching campaigns has never been necessary in the past—risk was just there, like light and shadow, part of the course of living. It was guided, as was so much else, by the combination of tradition and necessity. But modern society must stipulate everything now. The great irony of our species’ progress, to me, is that the more we fix, the more there is to fix. The more control we have, the more we must exert. Our safety-enhancing technologies have obvious upside—protecting and extending life—but the much-less-obvious downside of imbuing that life with fear and uncertainty.

So long as modern environments strip away the kinds of challenges that calibrate our risk systems and shape our character, we’ll be left with a society where everything seems perilous—and hardly anything is. To transform anxiety from a detriment into a tool, we must recognize risk as a vital input to our evolved nature. Only personal encounters with danger allow a person to say—this is scary, that is not—with any confidence.

Otherwise, anything can seem scary—and that is my answer to why so many of the safest people in the history of the world are anxious.

References

Lukianoff, G., & Haidt, J. (2018). The coddling of the American mind: How good intentions and bad ideas are setting up a generation for failure. Penguin Press.

Shrier, A. (2024). Bad therapy: Why the kids aren't growing up. Sentinel.

Twenge, J. M. (2023). Generations: The real differences between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers, and Silents—and what they mean for America’s future. Atria Books.

For an understanding of just how peaceful the modern world is compared to most of human history, see Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined.

https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/10/03/the-prevalence-of-peanut-allergy-has-trebled-in-15-years

p. 229

To be fair, this glosses over the difference between innate and adaptive immunity.

If you’re thinking, well, what about people who smoke a lot? Over time, they feel the burn in their lungs less, don’t they? True, but that’s because of cell death, so it’s not an adaptive response, but rather a side effect.

Biological preparedness is the precise phrase if you'd like to delve deeper into the topic. Also, have a peek at this video of babies and snakes. It’s surprisingly hard to watch, but the takeaway is important.

By the way, this argument is being made by some big names recently: John Haidt and Greg Lukianoff in The Coddling of the American Mind, Abigail Shrier in Bad Therapy, and David Rosmarin in Thriving with Anxiety.

p. 29

This idea is part of the more general hypothesis known as the Hygiene Hypothesis.

Courtesy of S.C. Gwynne’s excellent Empire of the Summer Moon.

In novels such as Altered Carbon, in which people live for centuries, characters are extremely risk averse. Even in fictional worlds, there is something lovely about having less to lose.

As a previously sheltered and risk averse person who has come to find a great deal of pleasure in “risky” hobbies, this post really resonated with me. It is so true how taking risks increases your confidence overall!

i think the "growth mindset" - the knowledge that you can just learn things is a superpower. that my brain is neuroplastic and all i need to do is practice.