What do therapists do with problems they can't solve?

Convert them into ones they can.

Hi all, before getting into today’s post, I’d like to introduce Earth to Authenticity, a Substack with some of my creative writing. If you or someone you know has interest in topics like “Modern Impediments to Romance,” a literary analysis of Fitzgerald’s Winter Dreams, or a short story about a short couple, come check it out.

The problem with certain kinds of problems

Clinical psychology tends to convert the kind of problems it cannot solve into ones it can. For the most part, this practice is not deceitful, intentional, or even confined to clinical psychology.1

There are at least four types of client problems that make mental health professionals uncomfortable: simple, environmental, exceptional, and unknowable. Let’s unpack why each type undermines the value of therapy, and how therapists tend to re-frame them into problems that can be worked on.

Simple, straightforward, apparent, obvious.

By and large, clinical psychology is allergic to Occam’s Razor—the idea that the simplest answer is usually best—because if the answer is obvious, who needs a professional?

The standard way that therapists complicate matters is by suggesting “something deeper” is at play. For example, my supervisor recently pointed out that I’ve missed several payments over the last six months. In thinking through a reason for this omission, the typical therapist would disregard the following:

My next session begins 5 minutes after I hang up with my supervisor, leaving me precious little time to use the bathroom or grab some water, let alone send a payment

Sometimes I forget to charge clients (i.e., maybe I am absent-minded across the board)

If I forget to pay my supervisor more often than I forget to charge my clients, it might have something to do with the fact that I enjoy acquiring money more than giving it away

Instead of these straightforward explanations, clinical psychology prefers the subterranean world of repressed feelings and unconscious drives—because those are the kinds of things it’s designed to address. Right on cue, my supervisor wondered aloud if maybe I am angry at her for not understanding me correctly, an anger I have been channeling subconsciously by withholding payment. (We have a great relationship, so I simply responded—“Nope, try again.”)

To take another example, I once sat through a case presentation2 in which twenty minutes were spent on what was “underneath” a client’s suspicion that she was unattractive. Did it indicate low self-esteem? Reveal a traumatic past? Was it part of a negative script? Evidence for maladaptive beliefs? All were possible, and it was up to the presenting clinician to figure it out. Not once did we explore the possibility that the client was unattractive.

Environmental, circumstantial, contextual.

Therapy is limited by the fact that it only has access to the client; the environmental factors that contribute to a client’s problems—including other people—do not come into the office. This often encourages clinicians to make the problem (and solution) more of the client’s responsibility than is fair. If the problem mainly lies with someone or something else, then what is there to talk about?

Take someone in an abusive relationship. In a courtroom, remedial efforts would be directed at the abuser. In therapy, however, because the abuser isn’t there, the abused becomes the agent of change.3 This isn’t to say that the abused is blamed, only that the onus for fixing the problem is on them. And is there anything in their past that perhaps suggests repetition-compulsion? Is there a subtle way they might be “encouraging” or at least “allowing” this kind of behavior to happen? If not, can the client find the courage, resolve, and confidence to change the situation, or else move on?

An example of this bias can be found in the average therapist’s dislike of “running away from problems.” The phrase itself suggests cowardliness and futility, the idea being that whatever the problem is, it resides in the individual and not their circumstance. Thus, moving on from a trying job or difficult relationship will only result in the same problem surfacing somewhere else or with someone else. But surely many problems are caused and sustained by environmental factors that are unlikely to be present in the next situation, no? Yet therapists too often assume that a durable feature of the client’s psychology is what needs improvement.

It’s really not much different if a therapist goes the other way and insists that “systemic issues” are to blame for everything. The point is that because therapists don’t work with clients in context, they don’t know how much of the client’s problem is due to the environment, the client, or the interaction of the two.

Exceptional, one-of-a-kind, rare, unprecedented.

If a problem has never happened before and is unlikely to happen again, what is the point of learning from it? That is the dilemma therapists face with client problems that are exceptional. For example, I once lived in a house with walls so paper-thin that it was as if the extremely raucous neighbors were in the room with me. While this would bother most people, it bothered me to an absurd degree. So, although the problem clearly involved both me and my situation, I was the far greater factor.

But of how much value would working on this issue be, given that it’s extremely rare? I’ve never lived somewhere before or since with that level of noise.

The most common therapeutic response to these scenarios, though, is to make them general enough that there is value to working through them—until the problem is conceptualized in such a way that it does share similarities with past and (likely) future events. For example, a client with an unstable boss might be asked if he’s ever encountered instability in the past. And is it possible that you, or someone you love, will encounter instability of some kind in the future? If so, might it be worthwhile to explore your response to it?—both how you’ve dealt with it in the past and how you’d like to deal with it in the future? Generally speaking, relying on abstract qualities of specific situations (e.g. instability) is a good way to make them general and therefore worth “working through.”

Unknowable, multiply-determined, complex.

Professionals are supposed to have answers, and this pressure is amplified for doctors and therapists, who have people’s lives and suffering in their hands.4 In fact, I think the existence of the DSM can be seen from this perspective—as a result of psychology and psychiatry needing to have an answer but not really having one. In the future, I guarantee that people will look back on the DSM much more as a cultural artifact than a serious scientific document. But at least it’s something.

How do clinicians respond to problems without answers? How can I explain, for instance, why some of my clients have taken half a decade to fully recover from heartbreak? Or why one of my clients only loves his partners after they have broken up with him? Another client approaches every new opportunity in her life by peeking through her fingers, as if expecting the worst. Another client recently began experiencing panic attacks during things he has never been consciously afraid of before, like flying, public speaking, and scuba diving.

Perhaps the most curious thing about all the cases that I cannot explain is that most of my colleagues can. Only, they would all have different answers, which I suspect is a result of needing to have one. But that’s the thing: humans possess an extraordinary ability to believe what is not true, particularly when there is no real way of testing the claim. Given the early stage of psychological science, almost anything goes—especially when the people being given answers (clients and their families) are desperately seeking them.

While we’re at it, the problem with solutions

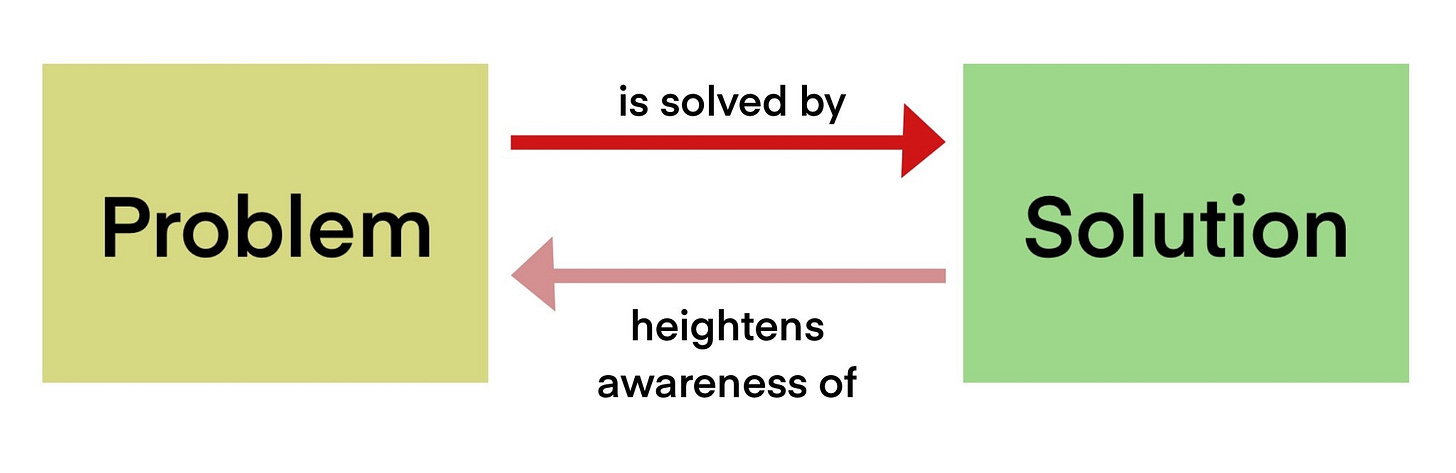

In addition to there being a problem with certain kinds of problems, there is also a problem with solutions. That is, as soon as a solution exists, it represents a gravitational force for problems. I explored this in The Art of Suffering Well using the example of a heated steering wheel. For most people, a cold steering wheel only becomes a problem once they learn of heated steering wheels. Before that, a cold steering wheel “is what it is.”

Likewise, I’m sure many people opt for in-vitro fertilization (IVF) who would have conceived naturally anyway. As the price of IVF falls, this choice will only become more common. The mere availability of IVF reframes the uncertainties of natural conception as problems to be solved—as problems that should not have to be tolerated.

In Bad Therapy, Abigail Shrier shows how the gravitational force of mental health solutions attracts problems that would never have existed otherwise. She opens the book with a striking example of suggestion: her son, brought to urgent care for a stomachache, was handed a mental health questionnaire that included questions about suicide.

It might sound far-fetched, but even questions as seemingly innocuous as “Do you ever feel suicidal?” have the potential to start a chain-reaction inside the mind of a young person, and all the more so when the question is asked multiple times in different ways. It’s quite possible that a child has never even thought of suicide as a phenomenon—let alone considered carrying it out—until the question is asked. Then, like any normal person, the child becomes curious. What’s it all about? Am I sad more than usual? Do I have a reason to live? Is there is a reason adults keep asking me this question?

We see this on a larger scale with suicide copycats. Some theories for why this happens involve the idea that copycats see the attention a suicide generates and want some of it for themselves. The simpler explanation might just be that when they see suicide, it becomes an idea. It has become something they can consider for themselves.

We tend to assume that the evolution of problems and solutions is linear: a problem exists and then a solution is created. We typically neglect the fact that the mere existence of a solution lowers the threshold for what is considered a problem.

The mental health industry has provided literally hundreds of diagnoses, as well as dozens of types of therapies and medications, to “solve” problems that were not considered problems in the past. Some of this has been positive, of course, but it’s hard to get a sense of how much has been negative. The inability to measure this effect, as well as the subtlety of the argument, means it is often dismissed or ignored.

The power of stories

The kind of problems that make therapists uncomfortable—I like to call them “problem problems”—often overlap. There is a good chance that a client in a hostile work environment will never meet with such a hostile environment again. The problem might also call for a simple solution: change jobs. But the basic point remains: therapy cannot admit problems which it cannot gracefully solve, so it tends to convert them into the kind it can.

By the way, my argument doesn’t hinge on which explanation is actually correct in any given case. A broken clock is still right twice a day, and therapists are surely sometimes correct when they say “there’s more beneath the surface” or that a client’s problems “will follow them wherever they go.” The point is that, whatever the truth may be, clinicians tend to favor interpretations in which therapy plays a central role—out of professional self-preservation. This isn’t usually deceitful, and often stems from a genuine desire to help. But it distorts reality all the same.

Sometimes, this warping of reality is no big deal. Other times, it comes with serious costs. A client from many years ago used to suffer at work because her boss was just downright horrible. The best solution for her was to get out. She did, eventually, but had I turned her problem into one that I was suited for— like encouraging her to stick it out as an “exercise in assertiveness”—I would have done her a great disservice. Yet therapists do this kind of thing routinely. Consider the opportunity cost: what is the client not doing because their therapist has them believing something that is neither here nor there?

Then again, it’s complicated. One of the most reliable ways to make suffering bearable is to make it meaningful—to fold it into a narrative. If my client had come to see her suffering as part of a larger effort to grow or improve, she likely would have suffered less. So I think it’s fair to say that this reframing would have both encouraged her to stay in the job longer (bad) and made the experience more endurable (good).

Believe it or not, much of therapy comes down to providing people with noble reasons to suffer—at least until they can make a change. In an odd way, then, sometimes the therapeutic tendency of making “something more” of a problem—one that has a much simpler explanation and solution—nevertheless provides the client with grist for the placebo mill. There’s almost something spiritual in the work at that point, and in our discussion of where therapists have led people astray, we should also keep in mind all those who have benefitted from the compelling, false stories of healers throughout the ages.

Anyway, I’ll have more to say about the placebo effect of therapy soon.

In The White Album, Joan Didion uses the phrase “perpetuating the department” to describe the tendency for any body or institution to preserve itself, perhaps especially when it stops adding value. She was, at the time, describing Los Angeles’ highway department.

A case presentation is when a therapist presents information about a client to a group of colleagues who then offer insight and advice on how to proceed.

In serious abuse cases, of course, therapists should contact authorities.

The basic discomfort of saying “I don’t know” when you’re supposed to know explains a good amount of human behavior.

I do think that one of the biggest reasons for problems 1 & 2 at least is that therapy is typically provided as a fairly expensive personal service to fairly materially comfortable people. There's a tacit assumption that "if it was that simple the client would have done that already". There's a tacit assumption that the lives of people who can afford and are willing to undergo therapy as at least roughly ok. And sometimes it's true. But sometimes the client is also in a similar mindset, of "it can't be that simple". And yet it can: for example acquiring practical means of doing certain things, or making things easier or less painful, can go a huge way towards promoting behavioural change, which in turn can do wonders for mental wellbeing.

Yes, there's something to be said for learning to tolerate distress, and therapy can help with this for sure, but the "change what you can change" is as much part of the strategy as "accept/reframe the pain you cannot avoid".

Oh and I LOVE the unattractiveness example!! I don't know if it's complicating a simple problem. It might be more than we're not "allowed" nowadays to consider ourselves physically unattractive, it's seen a problem with self esteem and never a realistic assessment.

Is meaning truly part of the therapeutic purview? Are we talking about care of the psyche or care of the soul? When is it appropriate for a therapist to suggest a patient see a priest, minister, rabbi, etc? Does this ever happen? Certainly, chaplains turn care over to therapists.