What to Do With Emotions - Part II

How to deal with evolutionary mismatch.

In the first article of this series, we presented a decision framework about what to do with emotions. The framework is useful, we hope, because our old emotions often motivate us to do things that, once upon a time, made a lot of (evolutionary) sense, but in the modern world… not so much. This post digs deeper into one important implication of that environmental mismatch: the difference between fitness-good and utility-good.

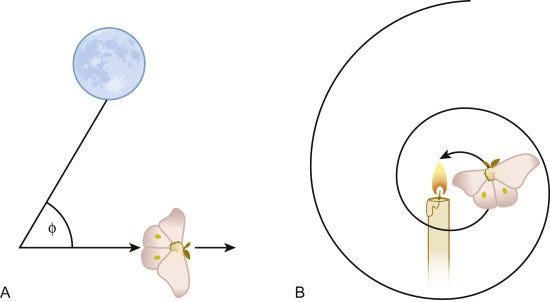

If your hand is burning, you have the urge to pull it away from the fire, which is fitness-good,1 meaning that it’s generally adaptive: such behavior would have increased inclusive fitness over evolutionary time. When time marches on and circumstances change, a perfectly good adaptation can go awry. Let’s use moths as an example. In the world in which moths evolved, Very Bright Things (VBTs, we’ll call them) were, generally, the sun (during the day) and moon (at night). If you’re a moth and the VBTs are for all intents and purposes infinitely far away, then you can fly a straight line by keeping a constant angle between you and the distant light source.

But then time marched on and a clever species made incandescent lightbulbs for their porches and scented candles for their parlors. Now, if you’re a moth, and you maintain a constant angle to this modern invention, you spiral right into the light source and pay the ultimate price. A system designed to measure the angle from moth to source and motivate keeping this angle constant works great when light is super-duper far away, but this system is deadly when h. sapiens make dangerous light sources that are close by.

Borrowing from economics, let’s refer to someone’s pleasure, happiness, or enjoyment as their utility. A behavior, choice, or strategy that leads to increasing one’s utility is utility-good. Symmetrically, let’s call all those Bad Life Decisions utility-bad.

Now, in the past, generally fitness-good and utility-good lined up. The whole reason something felt good was that evolution was pushing you toward adaptive behavior. The apple is yummy because its nutrients improve fitness. Similarly, if you’re a moth before humans started lighting tiny little fatal fires, it was fitness-good to use your evolved navigation system to get where you had to be, and it was probably utility-good as well.

Now, we have the feelings that we do—including strong emotions—for the same reason. As environments2 change, adaptations might behave oddly because the pace of genetic change lags behind many kinds of environmental changes. So, in the past, evolution guided us toward good fitness outcomes and doing so felt good. The problem is that what made an action fitness-good in the past now sometimes leads to utility-bad results.3

Let’s use these terms and ideas to review the case we discussed in the prior post in this series, road rage. In the environments in which humans evolved, if someone imposed some cost on you for only a small benefit, and—crucially—you were going to be seeing this person frequently, then, if you do nothing, that person learns that they can harm you with impunity and is more likely to do it again.4 Depending on the details of the cultural environment, letting petty insults go was fitness-bad in the long run.5

If, on the other hand, you hurt this person back, they (and observers) learn that crossing you has consequences. So, if someone steals one of your turnips to give to their pet rabbit, you might feel anger—in this case, a measurement of the cost of the theft to you—and decide to take revenge. This decision to take revenge is fitness-good because you have deterred subsequent harms. At the same time, it might very well be utility-good. Taking revenge can be very satisfying.6

Now, just as moths evolved in candle-free environments, we evolved in environments that didn’t have some modern accoutrements. First, there were no police. That’s not to say that there weren’t ways in which cultures enforced norms. No doubt there were. But today, taking revenge is often proscribed by custom and law, making it a bad idea. Second, while there is debate about the details, in the past, if you interacted with someone today, it was likely that you would interact with them again tomorrow, or at least soon. Because people didn’t travel far, they ran across the same people over and over. Interactions were repeated.7 This is crucial because the best strategy for repeated interactions is different from the best strategy for one-off interactions.8 Technology is a third: getting into physical fights is always dangerous, but lethal tools make it more so. The list of ways in which the present differs from the past is lengthy, and many of these ways undermine the utility of indulging one’s emotions.

So, to review the example we used in Part I, what is going on when someone cuts you off on the road? Someone has just imposed a cost on you, similar to stealing your turnip. You experience anger and, having read posts on The Living Fossils, you quickly realize, aha, I’m built for revenge. That’s why I’m angry. Revenge is fitness-good. Got it. Ok, now, will revenge advance my life goals? No, taking revenge will probably be utility-bad. So, being a wise and evolutionarily-savvy person, I shall pass.

Let’s take another example: fear. Prior human environments had plenty more potentially fatal threats than modern environments. Our ancestors genuinely had to worry about the possibility of being killed by big animals with nasty claws and stabby teeth, dying from infected wounds, starving, and so on.

Today, you might have the occasional shouting match with your neighbor about his yappy pooch, but it’s unlikely the conflict will turn fatal.9 We are, of course, never truly safe—tomorrow is promised to no one—but our lives are far less precarious than nearly everyone who ever lived before us.

Nonetheless, fear is part of human nature because of its fitness-goodness. In the past, seeing a fearsome beast bearing down on you probably meant that a fearsome beast really was bearing down on you. Today, if that’s happening, then you’re probably at a zoo or watching a movie. Darting out of the theater is not, as a rule, utility-good, especially if there are no refunds.

Now, one aspect of life that is similar to the past is other people. Humans are a very social species and, despite what you read on inspirational calendars, you should care about what others think of you. Other people control your employment opportunities, your mate choices, your social life, and much more. Social interactions are, therefore, like bets. Interactions can generate benefits—jobs, mates, invitations to parties—but they also present risks. A poorly-worded reply and you’re thought socially awkward. An overly-forward remark and you’re thought creepy. A good example is the line in Dirty Dancing in which Jennifer Grey first meets Patrick Swayze, managing only a wan, “I carried a watermelon.” And you never get a second chance to make a first impression.10

This perspective, that social interactions are bets, explains why being faced with them causes fear. When I (RK) was in graduate school, I foolishly sat down at a poker table with my friend who was doing just fine, thank you working at McKinsey. When he ponied up the $5 chip, I’m guessing he felt little fear.11 When I edged the chip onto the felt—and then doubled down, seeing my nine against the dealer’s six—I felt my heart race as I contemplated the day’s worth of food I was wagering.

Fear is evolution’s way of telling you that maybe you shouldn’t be placing that bet. It’s better, perhaps, to run away and hit the penny slots instead.

Let’s look at two kinds of social bets that might elicit fear. Suppose you are single and captivated by a potential mate—Patrick Swayze, say—who is across the room at a party. Fear is designed to let you know that you that you should carefully consider whether to make the bet. In ancestral environments, there might have been only a handful of potential mates nearby, meaning that blowing it with one of them by discussing watermelons might have drained a significant fraction of the mating pool. And a rejection might have stained your reputation to boot.

In short, just like Rob-the-grad-student betting $10, the stakes might have been high.

Today, we live in a bigger sea with a lot more fish, so the cost of ruining your chances with any given potential mate is lower. You still feel the fear that evolution supplied, but that fear is designed for a different environment, just like the pre-candle moth world. The impulse to freeze or flee might be fitness-good, but not utility-good anymore because the cost of failure is much lower while the potential benefits are higher.

Related, public speaking multiplies the chance of benefits and the risk of costs. This multiplied risk probably explains why people are so scared of public speaking. Evolution “knows,” if you will, that there are real risks. That fear is telling you that it might be fitness-good to run away and address the band another day. Whether it’s utility-good or not, well, you have to think about that carefully. Does anyone really care if you don’t plant the first toast to the bride and groom?

The first step in our little decision tree is to ask if the adaptive goal is still relevant. This question can help you decide whether to give into the emotion in the way that evolution intended or to tell evolution what it can do with its emotions so you can get on maximizing utility. Each emotion that you understand in the context of its evolved function will take you further along this path to utility-goodness.

The mismatch between the past and present environments makes it difficult to know what to do with emotions. A further complicating factor is that clinical and pop psychology promote questionable ideas about how emotions are generated, what emotions mean, and what people should do with them. Many of these ideas are confusing, conflicting, and, sometimes, straight-up incorrect. The next post in this series addresses these complications, so check back soon!

REFERENCES

Barrett, H. C. (2015). The shape of thought: How mental adaptations evolve. Oxford University Press.

Burnham, T. (2003). Mean genes: From sex to money to food: Taming our primal instincts. Penguin.

Delton, A. W., Krasnow, M. M., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2011). Evolution of direct reciprocity under uncertainty can explain human generosity in one-shot encounters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(32), 13335-13340.

Dunbar, R. I. M. (1992). Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates. Journal of Human Evolution, 22(6), 469-493.

Jones, O. D. (2000). Time-shifted rationality and the law of law's leverage: Behavioral economics meets behavioral biology. Northwestern University Law Review, 95, 1141.

Maynard Smith, J. (1976). Evolution and the Theory of Games. American scientist, 64(1), 41-45.

Nisbett, R. E., & Cohen, D. (1996). Culture of honor: The psychology of violence in the South. Westview Press.

Pinker, S. (2011). The better angels of our nature: Why violence has declined. Viking.

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1996). Friendship and the banker's paradox: Other pathways to the evolution of adaptations for altruism. Proceedings of the British Academy, 88, 119-143.

The shape of thought: How mental adaptations evolve, by Clark Barrett. If you’re thinking about picking up a copy, a conflicted reviewer on Amazon writes that it “is a brilliantly argued, wonderfully informative book that is as comprehensive as it is useless.”

By “environment” here I mean not just flowers and trees, but the social environment and everything else that’s relevant for the operation of a given set of adaptations.

For readers who want to go into more depth, there are several good treatments of this idea. See, for instance, Terry Burnham’s book Mean Genes. A good scholarly source is work by Owen Jones, who uses the term “time shifted rationality” to refer to these ideas. Search for “ecological rationality” with your favorite search engine for additional sources.

The part about the benefit being small might matter. It’s hard to deter people from harming you if doing so generates a very large benefit to them; you would have to impose a cost bigger than the benefit they stand to gain. Deterring small benefits is easier.

An excellent discussion of this idea, applied in a more recent context, is Dick Nisbett’s book, Culture of Honor.

A post on satisfaction is coming any day now. Note: revenge is a dish best served cold.

Delton et al., 2011.

Maynard Smith, 1976.

See Better Angels of Our Nature by Steven Pinker for an excellent and thorough treatment of just how much better life is now than it was then.

It worked out for those two though.

I think he expensed his losses.