In 1973, the American Psychological Association removed the diagnosis of “homosexuality” from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual.

Not everything that is viewed today as a “disorder” will necessarily be seen that way in the future.

Increased tolerance of differences is one important force in these changes in points of view. The evolutionary perspective offers another.

Tolerance allows us to view certain kinds of behaviors not as pathological but rather the result of differences in preferences. In certain respects, the rejection of this-shaming or that-shaming is the recognition that people are entitled to have whatever preferences they like, as long as one doesn’t behave coercively.1

The evolutionary view offers the possibility that certain kinds of behaviors that were once thought to be pathology might actually be the result of differences in strategy.

This idea might seem difficult to entertain for depression or, as the DSM would have it, Major Depressive Disorder.2 The symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder do seem to be pathological—that is, something is broken or not functioning properly—including lack of interest in activities, social life, and, of course, the possibility of self-harm.

Strikes

Stepping back for a moment, there are examples from everyday life in which self-harm is comprehensible as a strategy. Consider workers on strike. The details of strikes vary, of course, but in many cases, workers are voluntarily choosing to give up wages, even risking their future employment. These are potentially serious costs.

Indeed, these costs are a big part of what makes strikes effective. That’s not to say that the loss of the work isn’t effective as well. The cost to the employer of lost labor does give the boss an incentive to try to get everyone back to work. Still, the cost to the employee matters, too. If an employee tells their boss that they are so dissatisfied with wages and conditions that they are considering quitting, that is, as economists say, cheap talk. The boss can’t see exactly how much the employee hates their job and doesn’t know for sure if the employee is exaggerating in the interest of seeking a raise. However, if workers are willing to forgo wages, then owners are much more likely to take the complaints seriously. A strike is workers saying, “yes, I am going to suffer, but matters are serious and I really need more from you. Further, if you don’t change the deal, then I might not come back to work at all.” Circumstances have varied over time, but in many cases, strikers had to do without wages, with all the difficulties that loss entails. Strikes are painful for strikers.

The value of striking as a way to indicate displeasure with the current circumstances is consistent with signaling theory, which we’ve seen in other contexts. Cheap signals—whether in the biological world or the social world—are likely to be ignored. Costly signals—think peacocks’ tails and diamond rings—are likely to be believed.

The key point to take from this discussion of strikes is that in some contexts, effective bargaining can entail imposing a cost on both the other party and oneself.

Relationships Are Like Jobs

When people who live together are asked what fraction of the work around the house they do, the sum is typically greater than one. Someone—at least someone, but maybe sometwo—is exaggerating. But notice that this finding means that, whether they say it or not, many people would probably like their partner to do more of the work.3

More generally, while humans can be very altruistic, the fact is that we are evolved to compete. We would all like more time, attention, and support from our family, friends, and allies. They, in turn, would like more of the same from us. All the goodies we get and have to bestow are scarce, so a key part of social life is negotiating over scarce resources. We all want our partners to do more chores.

Further, just as in the case of employees, we all face a problem deciphering others’ needs. When I say that I’m just exhausted from work so honey could you cook dinner tonight?, am I really exhausted, or just feeling lazy? Relationships are continual negotiations over matters large and small, with ambiguous information about others’ true needs.

Finally, it’s important to note that social relationships are unlike jobs in one way. In some sectors, finding new employees might be easy, especially if the work is unskilled. One worker can be replaced with another. Families are not like this. If your parents reduce investment, you can’t switch to new parents. If your husband is not making efforts to care for the child, well, there’s only one biological father. Now, you might be able to find a new best friend or a new spouse, but the costs of doing so can be very high. Many people occupy a social niche that makes them difficult, or impossible, to replace.

Causes of Depression – Measurement

While I’m suggesting, drawing on work by Hagen (2011) and others, that depression might be a strategy, I want to be clear that this argument doesn’t entail that depression is anything other than horrible to experience. As many others have said, depression is more than simply being very sad. It is, as I can personally attest, a soul-crushing, debilitating, overwhelmingly horrible feeling.4

In terms of cause, while depression is not always brought on by negative events, it often is. (See, e.g., Devries et al., 2013). Physical assault, the death of a loved one, and divorce are all common antecedents of depression.

Sadness in response to such events makes a certain amount of functional sense. Sadness seems to be evolution’s way of directing your attention to the precipitating event, likely in the service of reflecting on how best to proceed given the new, worse, circumstances. The loss of a close friend, family member, or relationship requires reorganizing one’s social world, one without a key ally. This takes some thought.

Related, in the wake of big losses, one’s needs are greater than they were previously. Humans are deeply social creatures, reliant on others for any number of aspects of our lives. In many ways, our ability to accomplish our goals depends on the strength of our social networks. The loss of a key node in that network—family member, spouse, friend, etc.—represents a missing piece of one’s social puzzle that imposes real costs and increases the need for social support from others. Similarly, being physically hurt or losing a job also increases one’s need for support. Indeed, you often find out who your true friends are when times are especially difficult.5

Viewed from this perspective, sadness generally and depression specifically might be measuring the extent to which one has an increased need for help. The greater the loss, the greater the need, the greater the feeling of sadness.

Note how this idea connects to the all-too common phenomenon of depression following the birth of a child, post-partum depression. In this case, there is, again, a need for help, stemming not from a loss but from a gain: a new person to support and care for. This view, of sadness as a measure of need, helps to explain why the loss of a loved one and the addition of a loved one can have the same effect.

Symptoms of Depression - Motivation

Depression is characterized by very deep sadness, often accompanied by a withdrawal from the social world, a loss of interest or pleasure in activities, disorders of eating and/or sleeping, weight loss or gain. A sinister aspect of depression is a sense of hopelessness, that the pain one is currently experiencing will go on forever and that there is nothing that will reduce it. This hopelessness can undermine people’s interest in seeking treatment.

Another important symptom of depression is, of course, thoughts of death and considering—or attempting—suicide. This aspect of depression seems to weigh very heavily against an interpretation of depression as a strategy. How can killing oneself, the ultimate loss of fitness, be an evolved strategy? Suicidality makes depression look like a disorder.6 (I open with the point about homosexuality in part for this reason: it’s important to keep an open mind about what is and is not a disorder.)

If the analysis above is correct, that people occupy social roles such that it is difficult or even impossible to replace them, then each of us has a dangerous strategy to use to negotiate better treatment: the threat of suicide. Depression7 is someone saying, “yes, I am going to suffer, but matters are serious and I really need more from you. Further, if you don’t change the deal, then I might not come back at all.” This should sound familiar.

The case of post-partum depression, while painful to think about, illustrates this most clearly. From the perspective of the biological father and the mother’s relatives, the mother of a newborn is truly irreplaceable. No one else has a deeper interest in—or is in a better position to advance—the child’s wellbeing. In turn, this gives a mother leverage. From the perspective of the father and her relatives, the mother’s death would represent a tremendously large fitness cost.8

This argument holds for many different relationships. People are valuable to others as friends, allies, relatives, and so on. Yes, in some cases they can be replaced but, again, in many cases replacement would be difficult or impossible.

This view helps to explain some of the other features of depression. Withdrawal from the social world is a costly signal just like a strike is. Yes, the person themselves is missing out on valuable interactions, but so too are the person’s friends and allies. Unfortunately, the symptoms of depression have to work as costly, and therefore credible, signals. This view explains why depression imposes real, genuine costs on the person suffering.

Depression, then, motivates imposing costs on oneself that carry costs to others as well. At its most extreme, it motivates a threat to impose the ultimate cost.

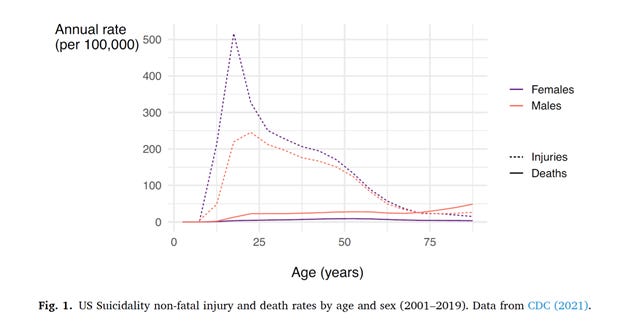

Now, on that note, it’s worth looking at some data. The argument that suicidality is a strategy becomes less persuasive to the extent that suicidality causes death. While, tragically, sometimes it does, it does so relatively rarely. Gaffney et al. (2022) illustrate this pattern with the graph below, drawing on data from the Centers for Disease Control:9

While, again, every death from suicide is a tragedy, the data suggest that there are many times more suicide attempts than completed suicides. Further, it’s plausible that modern technology has made suicide easier than it was in the past, given the invention of deadly tools. So it’s plausible that in the past, suicidality led to even a smaller percentage of actual deaths.

Viewed this way, it is plausible to view suicidality as a threat to end all one’s cooperation with friends, family, and allies, but the threat is only carried out rarely, making it something of a gamble. This is one of those rare cases in which the popularized version of psychology, that suicide attempts are a “cry for help,” might turn out to be correct.

While this topic is difficult to research for obvious reasons—we cannot randomly assign people to depressed versus not depressed groups—there is some evidence in its favor. Gaffney et al. (2022) gave subjects vignettes surrounding people who experienced a traumatic event. In a between-subjects design, people learned that the victim 1) asked for help verbally, 2) cried, 3) was mildly depressed, 4) experienced serious depression, or 5) attempted suicide. The results were that as the costliness of the signal increased (from the first condition to the fifth), subjects reported a greater belief in the victim’s genuine need and a greater willingness to provide support, consistent with a bargaining view.

Conclusion

Depression is horrible.

Having said that, lots of human experiences are horrible but also have a function. The reason burns hurt so much is that the pain causes you to pull back from fire and take precautions in the future. Pain, as unpleasant as it is, can be not just useful, but vitally so.

Psychological pain has a similar role to play. The brutal torture of depression is, to be sure, excruciating. That fact doesn’t, in itself, preclude the possibility that it’s has an evolved function, measuring the need for additional support and motivating sending costly signals of one’s acute need to family, friends, and allies including, unfortunately, the ultimate bargaining tool, the threat of suicide.

In the U.S., you can reach the National Suicide Prevention Hotline by dialing 988.

REFERENCES

Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y., Bacchus, L. J., Child, J. C., Falder, G., Petzold, M., & Watts, C. H. (2013). Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Medicine, 10 (5), Article e1001439.

Gaffney, M. R., Adams, K. H., Syme, K. L., & Hagen, E. H. (2022). Depression and suicidality as evolved credible signals of need in social conflicts. Evolution and Human Behavior, 43(3), 242-256.

Hagen, E. H. (2002). Depression as bargaining: The case postpartum. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23(5), 323-336.

Pinker, S. (1994). The better angels of our nature: why violence has declined. New York: Penguin Books.

Hagen, E. H. (2011). Evolutionary theories of depression: A critical review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(12), 716–726. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 070674371105601203

Hinman, A., & Dickey, l. B. (1956). Breath-holding spells: a review of the literature and eleven additional cases. AMA Journal of Diseases of Children, 91(1), 23-33.

Ronson, J. (2016). So you've been publicly shamed. Riverhead Books.

Ross, M., & Sicoly, F. (1979). Egocentric biases in availability and attribution. Journal of personality and social psychology, 37(3), 322.

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1996). Friendship and the banker's paradox: Other pathways to the evolution of adaptations for altruism. In Proceedings of the British academy (Vol. 88, pp. 119-144). Oxford University Press Inc..

Young M., Wallace J. E., Polachek A. J. (2015). Gender differences in perceived domestic task equity: A study of professionals. Journal of Family Issues, 36(13), 1751–1781

Well, ideally this is how tolerance should work. In reality, there are still an array of preferences which, even if not acted upon, are judged to be pathological and/or morally objectionable. Sexual preferences are like this, which is interesting in the context of the historical trajectory of homosexuality. It’s a little old now, but a good book—if only because of the title—is Ain't Nobody's Business If You Do: The Absurdity of Consensual Crimes in a Free Society by Peter McWilliams.

The criteria for MDD in the DSM-5 include depressed mood, reduced interest in activities, fatigue, weight loss or gain, problems sleeping, fatigue, and suicidal ideation. Not all need be present for the diagnosis.

The classic work on this is Ross & Sicoly (1979). They propose one key source of this result is that you are always present when you do housework but not always when your partner or roommate does it, so your memory is biased: it’s easy to recall when you did housework because you have a lot of memories to choose from. Perceptions of housework have, of course, changed since this initial work. See, for example, Young et al., 2013.

I feel that I need to add a rare personal footnote. I suffered from depression for most of my adult life so my remarks here blend my own experience with information from the scholarly literature. If you suffer from depression, I urge you to seek care. If you know someone you suspect is suffering from depression, please provide all the support you possibly can. There are two people who prevented me at two different points in my life from taking an irreversible action—they know who they are—and I will never forget them. Conversely, I can promise you that if someone close to you is depressed and you offer no support, they might well never forgive you.

See Tooby and Cosmides (1996) for an excellent treatment of this. People who were canceled by moralistic mobs—ahem—report being shocked at how few of their friends were, in fact, friends, abandoning them after decades of “friendship” or, worse, publicly joining the mob. See Jon Ronson’s book, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed for anecdotal accounts. Or see The Scarlet Letter for a fictional account.

Pies, 2014

I’m not saying that depression is the only origin of threats of suicide as a strategy. So-called “breath-holding spells” in young children seem to have the same general form. As Hinman and Dickey put it: “The spells are said to be an early infantile form of temper tantrum—a primitive expression of anger or frustration.” Generally, even non-depressed people have been known to say, “if you don’t [do such and such] I’ll kill myself,” with varying degrees of sincerity.

See Hagen, 2002

Rob Henderson linked to this interesting post. Got to thinking that maybe you are right about this. If so, maybe suicide is similar to an immune system overreaction, the result of strategies that when accumulated has the result of being self destructive to a fatal degree.

Very solid theory, I like it. Equating sadness with neediness also helps to explain why men are more likely to hide their tears in a public setting. I think there might be some secondary functions lurking in the background, (I find that sadness is usually an excellent way to de-stress, for instance) but this is an insightful take, thanks for posting it!