Recently, I’ve discussed some relatively straightforward sensations that people feel, using the idea that human experiences are designed to measure something relevant to fitness and motivate an appropriate adaptive response. That feeling that you have to sneeze, well, motivates sneezing out pathogens.

Can we use this framework to explain that thing with feathers, that many-splendored thing, that dream within a dream, love?1

Yes, this feeling is complicated. So, naturally, these ideas are more speculative than some of the others. Still, all the human feels are, I hypothesize, for something and ought to succumb to a functional/evolutionary analysis. But, having said that… this might be completely wrong.

Before digging in, I want to take a moment to revel my Gen X status and talk about the 1996 film Jerry Maguire. The title character, played by Tom Cruise, is fired from his job, managing sports stars. On his own now, Maguire works to persuade the athlete Rod Tidwell, played by Cuba Gooding Jr., to become a client. Tidwell is reluctant, of course, and makes the now-famous demand for Maguire to “Show me the money!” Tidwell also wants to enjoy an exclusive relationship. Maguire agrees to have no other clients and succeeds in persuading Tidwell to come on board. That relationship—as well as Maguire’s relationship with Dorothy Boyd, played by Renée Zellweger—enjoys great success and they all lived happily ever after. Would Tidwell have been better off signing with a big firm? Maybe. But with Maguire, he got commitment and, in the end, the money. We’ll return to this.

But for now, back to love.

First, what do I mean by love? I won’t try to define it. You know what I mean from your reading of Shakespeare, your viewing of romantic comedies and, if you have been lucky in life, your experience. Here I’m only talking about romantic love, rather than the love you might feel for your family, friends, and pooches. I’m focused on the feeling—holding aside any interference from Aphrodite—that Paris felt for Helen,2 a needfulness so intense he was willing to risk a war that would launch a thousand ships and give rise to a metaphor still in use today, not to mention the caution to beware Greeks bearing gifts.

I like the way that Dorothy Tennov discussed it, using her term “limerence.” When you feel limerent, you crave the object of your affection. You can’t think of anything else. You feel elated if they show signs of returning the affection. You are dejected by signs that they don’t. You neglect other parts of life in your pursuit of your beloved. You might, if lifted by the muses, compose poetry, music, or other art. (This last bit is an interesting clue.)

Love, famously, causes tragic failures of decision making, at least in myth and legend. Paris might be forgiven for falling for Helen, but was his next best option that much worse, given the stakes? Could Lancelot and Guinevere not have put their love aside, set against their loyalties to Arthur, King and husband? And when Romeo and Juliet believed the other to be dead, was suicide preferable to searching for another, though, doubtless, less compelling, mate? At first glance, love often seems to be, well, not very fitness-good.

Still, those who have fallen in love might be inclined toward not just answering each of these with a yes, but shouting its obvious truth with ebullient, confident enthusiasm. Who among us with the least poetry in our souls has not felt the unanswerably sublime pull of another, whose virtues so ensorcell that we feel as though we might fight, kill and, yes, die that we might be together?

In Book Three of the Iliad, the elders of Troy see Helen and remark:

"Small wonder that Trojans and Achaeans should endure so much and so long, for the sake of a woman so marvelously and divinely lovely.”3

So, yeah, small wonder.

Evolution is My Love Language

We’ll return to that quotation in a moment, but first let’s put some pieces on the table.

First, what’s the adaptive problem at stake here? While there is, of course, cultural variation, humans seem to be at least somewhat inclined toward monogamy. Humans are more complicated than, say, various bird species which are essentially exclusively monogamous, but monogamy is, it seems safe to say, one mating strategy in the human repertoire.

Second, while cultures again might vary, to achieve a monogamous mating, under many circumstances over the course of human history, the other party had to agree to enter into it. According to Homer, Helen left Sparta willingly, no doubt to at least some extent swayed by the power of Paris’ love.4 To be a successful monogamist often entails some kind of persuasion.

Third, it’s important to bear in mind that shopping for a mate is like shopping for a car in at least one sense. If your budget is limited, don’t bother pricing a Ferrari. That just wastes your time and annoys the dealer. As Steve Pinker put it, when you’re on the mating market, you’re not looking for the best of all possible mates. You’re looking for “the best-looking, richest, smartest person who would settle for you.” So if you’re, say, a seven—and by seven I mean not just looks, but all the traits that go into making one a good monogamous partner, which could include looks, sure, but also personality, age, status, and so forth—then if you chance across, say, an eight, well, you might just have found someone who, with some persuasion, might just settle for you. If you’re a seven, what would you be willing to risk for an eight or, heaven forfend, a nine?

Ok, with those pieces in place, let’s get to the measurement. When you come across someone very beautiful, rich, smart, and fun, you might recognize them as a highly desirable mate. Still, when you see George Clooney on the screen, you (probably) don’t fall in love with him. You might feel attraction—the subject of a future post—or even aroused—the subject of another future post—but it’s unlikely you feel limerent.

One possibility is that as we come across prospective mates, we are measuring both how good a mate they are—Clooney gets full marks—but, separately, how good a mate they would be for us. If you’re a seven, a ten is out of reach, a four is just a lack of ambition, but an eight, well, that would be worth a little effort and, perhaps, forgoing all others.

Which takes us back to Jerry Maguire. If I’m a famous athlete,5 then, sure, I might be able to sign with a big agency. If I do, I might do well but, at the same time, I’m just one of many. On the other hand, if I sign with Maguire, I get exclusive attention. Even better, because I’m his only client, he can’t ditch me. He needs me so much that to ditch me as a client would be to self-immolate. Even better still, I can enter into a legally binding contract with him so that if he does drop me or take on other clients, I have a powerful remedy, backed by the courts and the entire apparatus of the law.6

That last bit might start ringing a bell when it comes to romantic relationships. We too can enter into agreements, backed by the courts, that give us remedy if our partner abandons us and takes up with another mate. Marriage contracts recruit third parties to keep partners to their word.

What about a world in which no such contracts are possible because the apparatus of the state has not yet emerged? How can I signal to an eight that they should sign with me instead of that nine they have their eye on? I might say that I’ll be faithful, giving them the Jerry Maguire treatment, but how does she know my word is good? As we have discussed elsewhere, cheap signals are not honest signals.

Robert Frank suggests an answer in his book, Passions Within Reason. What if you could signal, somehow, to a potential mate that under no circumstances would you leave them because you are irretrievably and irrevocably smitten, unable to alter your course of affection if even you could? You might, for example, burn precious time composing sonnets, songs, and soliloquys, abundant with alliteration. These costs, just like the costs that serve to make other kinds of signals honest, might persuade the eight-of-your-dreams that she might just be better off with the Maguire treatment rather than throwing in her lot with another nine who might be tempted at some point to seek a ten.

According to this view, the thrill of limerent love is motivating costly signaling, including reducing time with allies, creating art, and generally reducing the priority of other fitness-building pursuits. This sort of strategy only works if one genuinely bears the costs and, importantly, the more visible and robust the costs, the better. This idea might even help to explain the depression one experiences after rejection, a kind of last-ditch effort to signal just how valuable the lover is to the loved, evoking peak grief.

Even with all of these ways to bear costs, some critics have worried about Frank’s answer. As a commitment device, love relies on signaling one’s true and deep feelings, perhaps especially in verse, which is all to the good. But how good are these signals, really, at ensuring that the lover doesn’t leave at some point down the road? Nothing in poetry’s dulcet voice prevents abandonment in life’s shadowy future. When Romeo avers that his heart never lov’d till this night, why should Juliet be swayed? Flowery verse, even set to iambic pentameter, succumbs to the economist’s charge of cheapness. Is it not as easy to leave a relationship that began with literary flights on Cupid’s wings as one that did not? To put it plainly, maybe Romeo was lying to Juliet. It happens. Can people persuade others that they are genuinely in love when it’s possible that they are mimicking what people say when they are in love?

For Frank, the answer is that as a psychological matter, people are simply unable to show these symptoms of love unless one is genuinely in love, making the symptoms a reliable cue to the affliction. This argument is that you need love’s muse to create a powerfully moving sonnet or song.7

Love is a Bridge Burner

Are there ways to make the signal more believable by making it more costly? Suppose that it’s true that people are better off when they have a larger, rather than smaller, group of close friends. If friends are used as allies, for support when conflicts arise, then more is better.

If so, then one way to convince a romantic partner that you aren’t likely to leave is to reduce your friendships, which makes you more reliant on your partner when it comes to alliances. This puts all of your eggs, as in were, in one basket. To signal that you are less likely to leave, then, you might begin to neglect even your closest friends and allies to spend time with your beloved.

Now, adding a lover might reduce the number of close friends one maintains simply as a side-effect of spending time with them. Many years ago, I started a tiny line of research on this question. We—this was work with an undergraduate in my lab at the time—did a little priming study, a technique that, candidly, I have almost no confidence in. We had some people read a story about love—or a control story about a normal day—and then asked people how they were inclined to spend their time after the experiment. From the abstract: “We found that individuals in the love prime reported being less likely to spend time with friends after the experiment than individuals in the control prime condition, but that these primes did not influence the likelihood of doing other activities.”

We referred to this as the “bridge burning” study in the lab because the idea is that love makes you burn your bridges with friends (and because of, speaking of Gen X, the 1988 song by the Little River Band). Anyone who has watched a friend disappear into a new relationship knows what I’m talking about. Perhaps it’s persuasive to be with a partner who relies on you for their social relationships, having forsaken others in the courtship.

All the symptoms of love—the rumination, the abandonment of friends, the resources expended, the psychic struggle—might persuade a potential mate of the depths of one’s feelings, but, if all of this is right, then being in love imposes some serious costs. The obsessions of love seem to radically tilt tradeoffs toward the pursuit of the target of one’s affection and away from nearly everything else.

Love’s Labour’s Lost

In sum, the feeling of love might measure something like the difference in mate value, designed to detect and identify potential mates who would be a great catch but at the same time could well be out of reach. This feeling, in turn, motivates paying certain kinds of costs to persuade the potential mate that you are—and will be—well and truly committed, making you a more valuable mate than one showing no such signals.

It should be clear that if this is the case, then a thorny issue immediately arises. People being pursued are likely to feel that they can command a higher value partner than the person pursuing them. This dynamic might help to explain in part why love is so fraught and why happily ever afters seem less common than broken hearts.

Postscript.

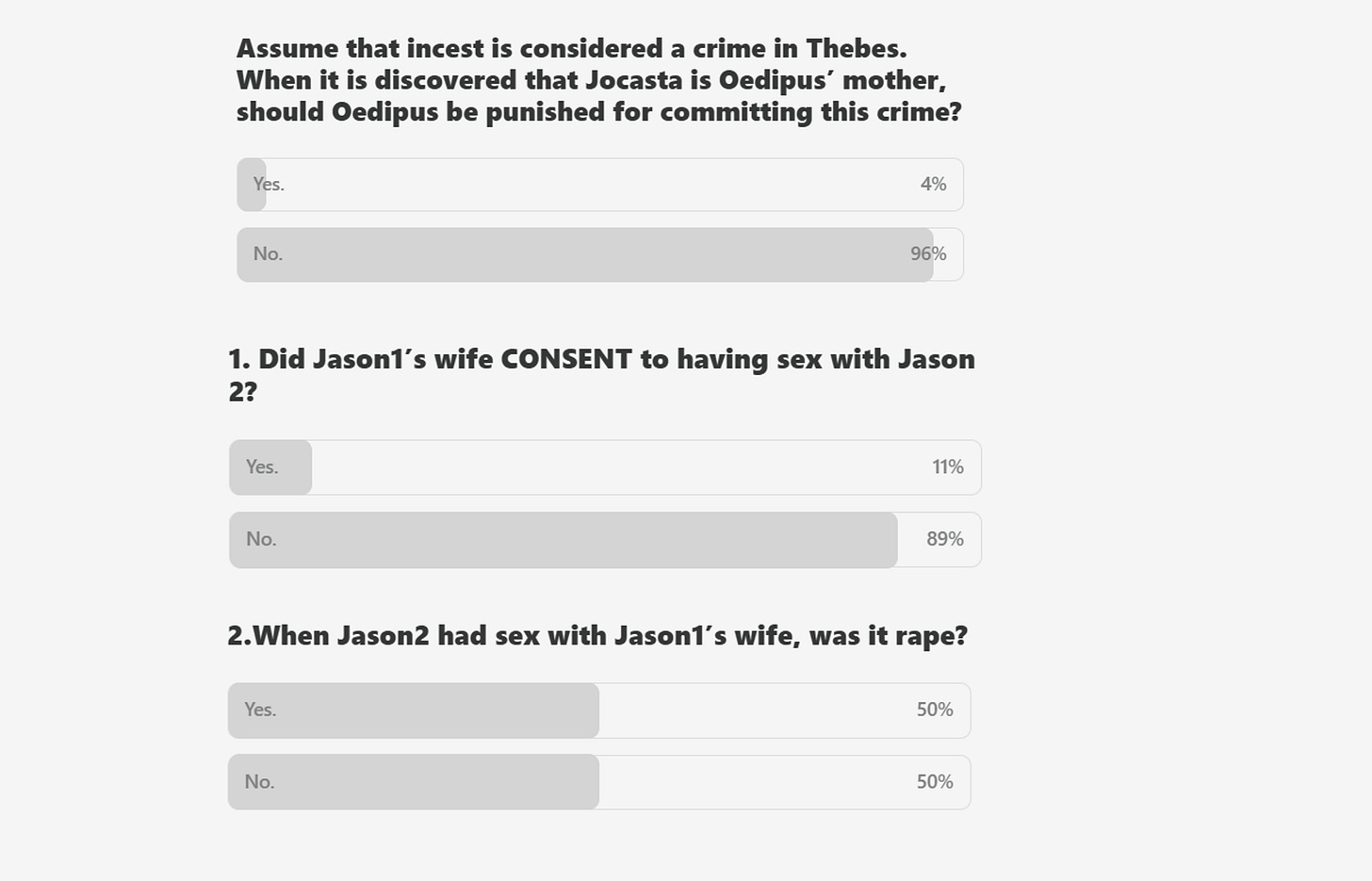

In my last post, I promised the results of the polls. Here they are:

So pretty strong consensus on the first two, even split on the third. These results seem to indicate that a substantial fraction of respondents believe that Jason1’s wife didn’t consent to having sex but that Jason2 nonetheless didn’t rape her. See the results of Aella’s polls on this topic for additional data on this topic.

CITATIONS

Frank, R. (1988). Passions Within Reason: The Strategic Role of the Emotions. Norton.

Pillsworth, E. G., & Haselton, M. G. (2006). Women's sexual strategies: The evolution of long-term bonds and extrapair sex. Annual Review of Sex Research, 17(1), 59-100.

The ideas in this piece appeared in a couple of blog posts some time ago. And, yes, I know that it was mawage, not love, that was that dream within a dream in The Princess Bride.

You’ll recall from a few weeks ago that, having spent considerable time recently in Greece, these posts were going to have a certain density of references to the history and myths of that civilization.

Accounts vary. Aphrodite seems to have played a role.

I am not. This is your regular reminder that I do CrossFit though.

Marriage laws enforced by the state are the analog. Many cultures use police power or, more informally, the community, to punish those who violate the agreement of the marriage contract. This is a topic about which Martie Haselton, for example, is something of an expert. See, e.g., Pillsworth & Haselton, 2006.

If love works as a signal that one won’t leave if someone better comes along, then marriage contracts can take up much of the work. That is, up until the contract, love might serve to persuade the other person that the lover is indeed disinclined to leave, keeping them around. Once the contract is formalized—with a ring, a ceremony, a certificate—then that contract does the work, making it much more costly for the lover to leave because of the consequences. This view might explain why love, sadly, fades. It’s there to get to the monogamous finish line and then let the community take up the work of keeping the couple together.

As a biology person, I would argue that the purpose of love is to keep the male partner around to provide for and protect his offspring. Human infants are costly. It is not possible for a mother to care for her child and support herself at the same time without help. The biological adaptation that has evolved is love. Cultural ones include marriage customs and strict gender roles in (virtually?) all traditional cultures which force male/female cooperation.

I think it was Schelling who argued that the tradition of pricey engagement rings makes commitment credible, abandonment requires significant expenditure on another ring. Rings can be returned of course but cut flowers and fancy meals can't, so become routine courtship activities.