How to Understand Human Behavior (Part 1/4)

Understanding the person.

Why do people do what they do? It’s a question that has invited answers ranging from divine will and unconscious drives to incentives and free choice. But if you strip behavior down to its bones, the logic is fairly simple. As Kurt Lewin put it in Principles of Topological Psychology (1936), “Behavior is a function of the person and their environment.” In mathematical terms:1

Where:

B = Behavior

P = Person

E = Environment

This formulation has stood the test of time. Seventy years later, in The Happiness Hypothesis (2006), Jonathan Haidt repurposed it as B = C × S, where behavior arises from character interacting with situation. Basically the same thing. My guess is that most readers would sketch a similar equation, if they could be convinced to sit down and do math.

Below is my own version. You’ll see I added some twists:

Where:

B = Behavior

S = Situation (slightly different than environment; akin to circumstance or context)

P = Person (species-typical in design, unique in expression)

That is, behavior is roughly a function of the person in their situation.

The changes are subtle but—in my opinion, at least—important. First, the squiggly symbol (≈) means “approximately” or “largely determined by,” rather than strict equality. Life is complicated, after all, and as Daniel Kahneman reminds us in Thinking, Fast and Slow, “We are far too willing to reject the belief that much of what we see in life is random.” A lot happens for no discernible rhyme or reason, including the ways you and I sometimes behave.2

Second, I wanted my equation to emphasize that the situation is usually the most important factor in human decision-making. The person in the situation still has a say, but the situation predominates. It was encouraging to see this idea—which I wrote about in excruciating detail in my Technology series—echoed in the book I’m currently reading, Unforgiving Places: The Unexpected Origins of American Gun Violence, by Jens Ludwig.3 Ludwig writes, “The risk of gun violence involvement seems to be more about the specific neighborhood than about the specific person” (my italics).

Finally, while Lewin used “environment,” I prefer “situation.” I think it more accurately captures the active variable. If I’m walking through the woods and hear a twig snap, it’s not “the woods” in general that determines my next move—it’s that, at dusk, alone, while walking, I heard a twig snap. That’s my situation, of which the environment is only a part. We can think of the environment as a static context—like the design features of a neighborhood that increase the risk of gun violence, from vacant lots to poor lighting—and the situation as a dynamic configuration of the relevant variables, like a person entering that neighborhood with a motive and a gun on a Tuesday night.4

In the rest of this series, I’ll put some flesh on the bones of this simple formula. If I’ve learned anything from researching and sitting with this piece, it’s that there’s far more hiding in those deceptively plain variables—person and situation—than first meets the eye.

The Person in Question

Two kinds of difference.

What do we always hear about people? That they are different. Indeed, it only makes sense that humans, being human, would be obsessed with their differences. (Turtles, by contrast, are probably obsessed with differences between turtles.)

But “people are different” is one of those phrases that explains everything and nothing. It rivals “it depends” as an all-purpose way of saying, “I have no idea, but I’d like to sound wise nonetheless.” (I once had a supervisor who relied on those two gems about ninety percent of the time, which is why I still shudder when I hear them.)

A more precise—and helpful—way to put it is that humans are defined by two kinds of differences:

how they differ from other species, and

how they differ from each other.

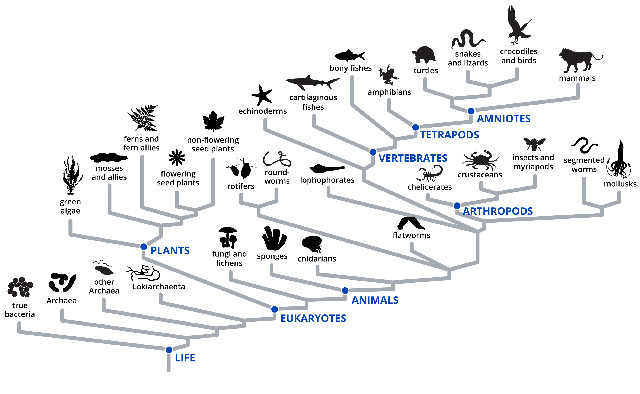

You and I are different from bears, E. coli, and trees because humans have a different evolutionary history. This history is best captured in the branching structure of phylogenetic trees, like this one:

Your and my shared lineage explains our similarity: why we both spent nine months in our mother’s womb, why we both have two hands with opposable thumbs, and why we both possess the capacity for sexual jealousy, even if one of us has never felt it before. (Please don’t sue me if you don’t have two hands.)

You and I are also different from each other—in two ways. First, we began with different genes. Second, different things have happened to us since. These two differences create three main pathways for variation. I can differ from you primarily:

Genetically—for example, in height or sex. (Heritability measures how much of the variation in a trait, such as height, is due to genetic differences. For height, the heritability is roughly 80%, meaning genes account for most—but not all—of the variation.)

Experientially—for instance, I’ve had about four concussions in my life. You?

Interactively—Many of our differences arise from such an ongoing, complex interaction between genes and experience that it would be difficult to tease out the dominant player. As Tooby and Cosmides (1990) put it, “Anyone with a biological education acknowledges that…all aspects of the phenotype are equally codetermined by this interaction” (p. 19).5

Put another way, every person is a combination of two parts. One is the species-typical foundation: a reliably developing set of features shaped by our long evolutionary history, including a stomach, a limbic system, the capacity for surprise and anger, the ability to grok culture, and hair. The other is individual variation: a distinctive pattern of settings across these shared traits that makes each person unique.

The key takeaway is that most human differences are quantitative, not qualitative—differences of degree, not kind. Humans and turtles differ in kind: we regulate temperature internally (endothermy), while they do so externally (ectothermy). But the fact that you get more irritable than I do when hungry, have a slightly drier sense of humor, or stand a few inches taller—those are differences in degree. As Tooby and Cosmides (1990) write, “No two stomachs are exactly the same size or shape, [but] each…has the same basic design” (p. 29). The same can be said for most of what makes us human, physical and mental alike. Which is why, as the Roman playwright Terence said, “nothing human is alien to me.”

Returning to my notation—B ≈ f (S(P))—we can break P down further into Ps and Pi, where Ps represents the species-typical base and Pi the individual variation. In mathematical terms, we might think of human nature as the mean, and individuality (or personality) as the variance.

Other than being interesting and true, why does any of this matter? Because variation among situations is typically greater than variation among people—meaning that while our reactions differ mostly in degree, the contexts in which we find ourselves often differ in kind. That’s why, on average, the situation outweighs the person as a factor in behavior, whether the behavior in question has to do with mental health, gun violence, Good Samaritanism, risk-taking, or consumer spending.

Spectrums and Individuality (or Personality?)

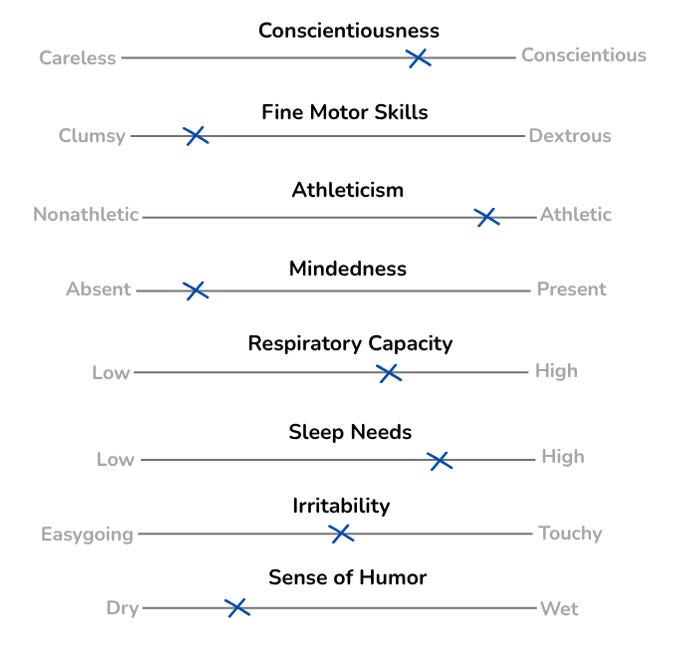

If human differences are mostly quantitative—different settings on shared traits—then individuality amounts to a unique constellation of positions along countless spectra: conscientiousness, proneness to anger, athleticism, fine motor skill, and more. Below is a rough sketch of your beloved author:

Now, you might consider the following detour a little indulgent, but I find it interesting, so buckle up. Do we consider the above my individuality or personality? To me, it seems that we—by which I mean WEIRD people—informally treat personality as a subset of individuality. For example, we don’t usually think of someone’s height, athleticism, or lung capacity as part of their personality, do we? But we certainly think of their irritability, conscientiousness, sense of humor, or absent-mindedness as such, no?

Then again, returning to height, we’re more likely to treat it as part of someone’s personality if it stands out (lol). In this, I think some of our animalistic roots peek through. We anthropomorphize traits, reading personality into physical features and assuming, for instance, that a tall person is languid, a short one fiery, an athletic one confident. Of course, such interpretations vary across time, culture, and observer, but we reliably “read into” the data available to us, inferring deeper qualities from surface cues.

So even if height isn’t part of our cultural understanding of personality per se, we sometimes make it one—especially when it’s remarkable in either direction. The same goes for traits that are considered part of personality. Don’t we only notice someone’s conscientiousness when it’s at the extremes? Otherwise, we kind of ignore it.

In this view, personality is both how we stand out and how others tell us apart. While we might think of some traits as more “personality-ish” than others, we ultimately rely on whatever distinguishes. “I’m sure you’ve met Tina. Beautiful, into horoscopes?”

Ok, enough speculation for now. Let’s return to the Portrait above. What determines where someone falls along each spectrum? Their unique history of gene–environment interaction.6 Exceptional respiratory capacity, for instance, might run in a family, result from frequent exercise, or both.7

But wait a second. What determines the course of evolutionary history—the branching of the phylogenetic tree above—if not each species’ history of gene–environment interaction? That is, the same process that shapes individuation also shapes speciation. The difference is merely one of scale: one unfolds within a single lifetime, the other across evolutionary time.

The Adaptive Range.

What determines the bounds of each of these spectra? In other words, why might your motor skills be twice as good as mine, but not a hundred times better? Because motor skills that good—or, in my case, that bad—would have been either overkill or inadequate for the job of surviving and reproducing.8

The range of genetic predispositions for any given trait can be thought of as its adaptive range—the span within which natural selection “allowed” that capacity to vary. Our ancestors within that range did well enough to pass their genes onward; simply being somewhere on the spectrum was good enough. Variance itself, meanwhile, is evidence of a trait’s relative unimportance: hair color varies more than leg number because hair color doesn’t matter nearly as much. The adaptive range is universal; where one falls on it is individual.

There’s an obvious qualifier, though. Take irritability. My position on the spectrum above ignores the fact that, much to my chagrin, I’m way more likely to be irritable toward my wife than toward a stranger I neither know nor love. My predisposition for irritability, in other words, remains sensitive to context—to who I’m being irritable toward and under what circumstances. That’s the situation.

Conclusion

Before moving on, let’s recap what we’ve learned about people. For understandable reasons, humans over-index on personal rather than situational differences, a bias that is perhaps amplified in the helping professions. This tendency is so common that it has a name: the fundamental attribution error.

In reality, humans are more alike than different, and what compels us to act differently is mostly the different scenarios we find ourselves in. Each of us can be understood as a human in a particular situation, with a history of particular situations.

Which makes the particulars of the situation—the subject of the next post—crucial to understanding human behavior.

References

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1990). On the universality of human nature and the uniqueness of the individual: The role of genetics and adaptation. Journal of Personality, 58(1), 17-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00907.x

To be fair, Lewin never wrote this formula himself—he only stated the idea in words. The notation was added by his translators, Fritz and Grace Heider, as a concise way to capture his principle.

Randomness pervades everything I will write about in this post. It was a mainstay of our evolutionary history in that genetic mutation is random (although not randomly selected for); it is a mainstay in the development of each human life (sexual recombination is to some extent random; developmental errors are, as well). There is also much arbitrariness in how our lives unfold, in the information we get presented with, how we interpret that information, how we choose to act on it, and how that action results.

Shout out to my friend Steve—a dedicated Living Fossils reader if there ever was one—for the recommendation.

To be fair, many who use “environment” in their formulation of human behavior intend a broad reading that largely overlaps with what I mean by situation. I’m making the distinction nonetheless because most readers won’t be aware of that nuance, nor will they infer it from either formal or everyday uses of the word environment.

By the way, what I’ve described so far is essentially a restatement of behavioral genetics.

For a technical discussion of gene-environment interactions, have a look at this brief post by Steven Pinker.

And don’t forget about randomness. As Steven Pinker notes, “[Scientists] are increasingly forced to acknowledge that God plays dice with our traits.”

Or there is some other constraint, such as tradeoffs, physics, path dependence, and so on.

saving for later. im excited

“what compels us to act differently is mostly the different scenarios we find ourselves in.”

Humans are social beings. We use status in the form of prestige (conspicuous competence) and propriety (norm adherence) as currencies of social cooperation. Different cultures frame similar situations differently. Human happiness rests to an almost startling degree on connections.

Your analytical framework seems to turn situation into *individual* situation too quickly.