Morality is a Coordination Game - Coordination Part IV

Why thou shalt not steal, really.

This post is the payoff for those of you who have been taking the long journey with me through the posts about animals, people, and athletes playing coordination games. On the other hand, maybe the real payoff was what we learned about cicadas along the way.

Let’s back up for a second and look at moral rules from 35,000 feet. Moral rules are, most basically, shared beliefs that certain actions (or, sometimes, inactions) are wrong and deserving of punishment.1 A moral rule is typically a prohibition that applies to everyone in a society, such as do not commit murder. Moral rules can also be duties. You must pray five times per day. The key element is that if someone takes the specified action, others judge it to be wrong or immoral.

With that throat clearing out of the way, here are three very basic facts about morality from the scholarly literature.

First, people everywhere make moral judgments.

Anthropologist Richard Shweder, among the world’s leading figures on the relationship between culture and morality, put this clearly:2 “Descriptive fieldwork on a worldwide scale … has of course demonstrated that moral judgments are ubiquitous in human groups.”3 He added that “moral judgments (that’s good, that’s wrong, that’s sinful) around the world are also felt,” likening these feelings to “aesthetic and emotional reactions” (p. 89). Morality, he’s saying, is a universal human sense.

Second, there is tremendous variation in what actions are considered to be wrong. Again, quoting Schweder (p. 90):

At the same time, fieldwork by anthropologists has also documented that as a matter of fact many concrete moral judgments about actions and customs do not seem to spontaneously converge across…cultural groups. Actions and cultural practices that are a source of moral approbation in one community (for example, polygamy or female genital surgeries) are frequently the source of moral opprobrium in another, and moral disagreements can persist over generations, if not centuries. Indeed, the history of moral anthropology as an empirical undertaking is in some significant measure the history of the discovery of astonishing cultural variations in human judgments about the proper moral charter for an ideal way of life.

In short, a lot of what anthropologists have been up to is documenting variability in moral judgments. The excellent work of Jon Haidt, Oliver Curry, and colleagues has enriched and extended our understanding of this moral variation. These lines of work document4 how groups vary in which moral rules they endorse and emphasize as well as the different foundations on which different moral systems rest.

Having said that, the third basic fact is that some moral rules are universal, or nearly so.

Some evidence for universality derives from observations that children develop complex moral intuitions from a young age5 and, additionally, all languages—as far as we know—have words for moral concepts, such as “obligatory” or “forbidden,”6 in line with Schweder’s observation about the moral sense.

Further, some actions are universally prohibited.7 In his book Human Universals, Don Brown noted that prohibitions seem to be common across human societies, including those against murder and incest, for example.

Subsequent work vindicated these views. John Mikhail, in a thorough study of murder, concludes that “individuals throughout the world recognize that intentional killing without justification or excuse is prohibited, and that self-defense and insanity, and to a lesser extent necessity, duress, and provocation, can sometimes be potentially valid justifications or excuses.”8

Related, some researchers have posited that there is a universal incest taboo, a prohibition against sex with close relatives. Early work by George Peter Murdock in his broad review of cultures concluded that “incest taboos apply universally to all persons of the opposite sex within the nuclear family.”9 While there is ongoing scholarly debate, at a minimum it appears as if the incest taboo exists in most, if not all, cultures.10 Deb Lieberman, in a series of excellent papers, has more recently shown that the aversion to incest, and the disgust that accompanies considering it, is widespread. An intriguing question—answered below—is why do cultures bother to forbid an activity no one wants to do in the first place? (The sports analogy would be something like prohibiting people from carrying large weights in a 50-yard dash. Sports generally don’t have rules like this.)

In sum: 1) making moral judgments is universal, and while 2) some moral contents (incest and murder prohibition) are universal or nearly so, and 3) many other moral contents are variable, cross-culturally and over time. If I’ve done my work properly, this summary should remind you of a very basic lesson from this series on coordination: “If you see between-culture variation in contents…then a good candidate for what those contents are up to is solving a coordination game.”

The Games

Can we think of moral rules as the results of a coordination game, analyzing them in a way that is directly parallel to the way we analyzed cicadas, butterflies, and penalties? I hope so. If you haven’t already, please read the earlier posts on this topic because the analysis here is meant to be strictly parallel. If you were persuaded by those other posts—that the phenomena we visited could be usefully analyzed through the lens of coordination games—then you ought to be persuaded by this analysis.11

Recall that in the case of sports, the benefit was to do with measurement: Who’s the best? But humans play other kinds of coordination games. For example, cultures coordinate on the various rules surrounding etiquette and manners. Forks on the left, spoons on the right, that sort of thing. If the invitation says the party starts at seven, what time do you arrive? In some parts of the world, arriving at seven would be rude—the “fashionably late” equilibrium. In other parts, arriving much after seven would be rude—the “punctual” equilibrium. As long as everyone in the culture knows the norm, people having parties know when to expect people and people attending them know when to show up. The particular norm—the contents—doesn’t matter. As long as people coordinate, the benefit is that they have good expectations, allowing for good planning. Everyone wins.

In the games I discuss below, when players don’t coordinate, you’ll see (red) payoffs of zero for both players. The basic idea is that there are benefits to having the same moral commitments as others; if you don’t share the same belief, then you don’t get the benefit, so no payoff. How far can the proposal that there are benefits to sharing moral beliefs get us in terms of explaining similarities and differences in moral contents?

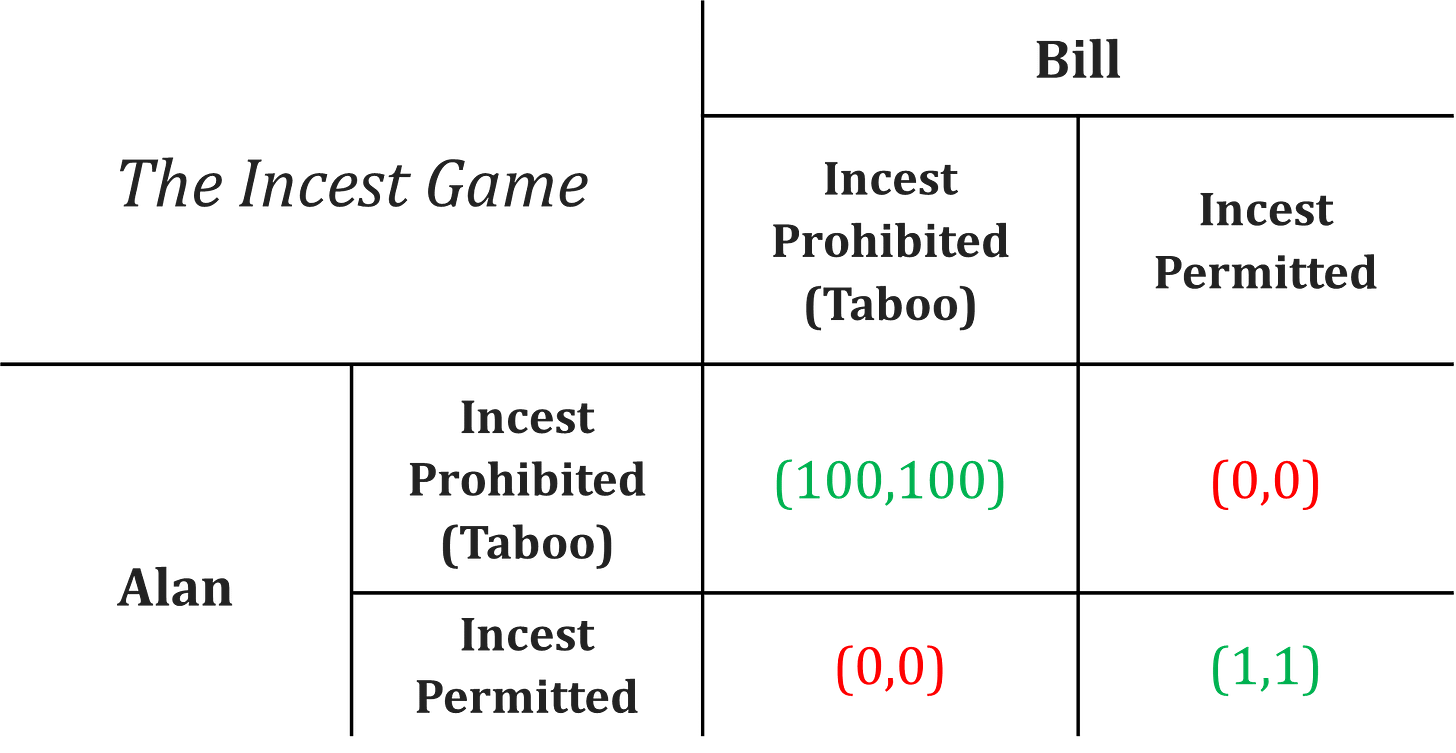

Let’s start with the Incest Game as we try to puzzle out the incest taboo.

This grid is no different from many other grids we’ve seen in this series. Indeed, it’s very close to the game I used to look at rules about wearing a helmet. We assume that there is a benefit to coordination, just as in sports. However, because of the cost of inbreeding and the associated disgust that people feel about committing incest—this is a reminder to see Deb Lieberman’s excellent work on this—people are attracted to the norm that prohibits incest. The disgust that people feel about incest acts as a kind of magnet, drawing them to the prohibition.

Because everyone has the same anti-incest adaptation, all players prefer the prohibition over the requirement, analogous to the hockey helmet case, in which players strongly favored the requirement. In addition, because of the benefits of coordination, people’s preferences reinforce each other—when others favor the ban, I benefit from supporting the ban. From this, we can explain why incest taboos are, with some historical exceptions, similar around the world. People want to coordinate on norms and, in addition, there’s a very strong equilibrium selection magnet—people’s disgust about and aversion to committing incest—pulling in the direction of the prohibition and away from the requirement.

Think about activities that most people find disgusting which are prohibited. Consider what might have happened if someone proposed a new rule prohibiting that disgusting thing. Thou shalt not eat thy poo. How much support would such a rule receive? Probably a lot. This very simple analysis explains why cultures bother prohibiting things people don’t want to do anyway. If there is a benefit to coordination on norms, then prohibiting disgusting actions is easy. Such proposed rules face limited—though not necessarily zero—opposition.

Again, this analysis is no different from cases such as the hockey helmet. You might prefer that helmets are optional. But when you play hockey, if everyone has agreed beforehand that helmets are required, then not only do you wear one, but you support punishment if someone doesn’t. To play the strategy is to support the view that, once the agreement about the moral regime has been reached, you support calling the violation wrong and punishing the wrongdoer.

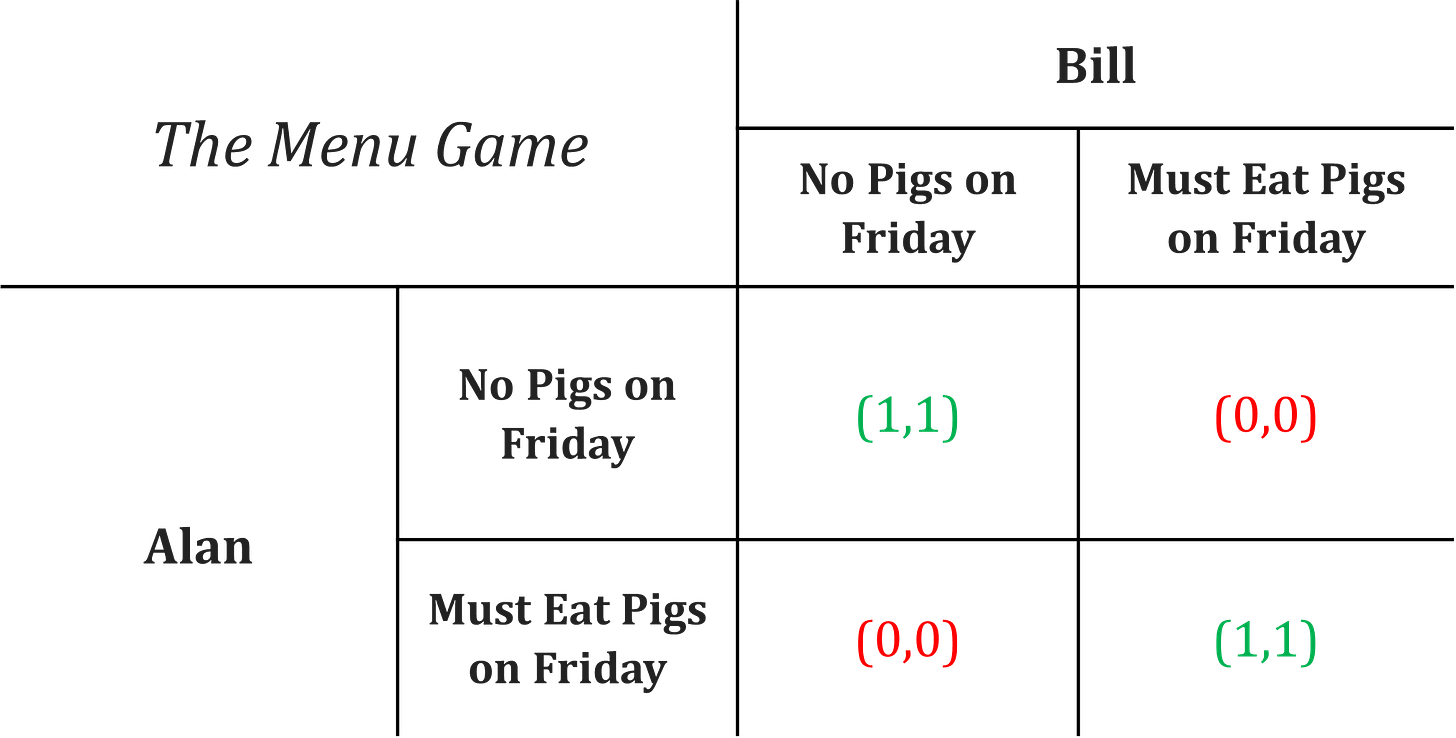

Now let’s play the Menu Game. Cultures have many rules about what may, must, and must not be eaten, often in terms of combinations, timing, and so forth. Fessler and Navarette (2003), for example, observed that “Cultural understandings concerning food, edibility, contamination, and related topics exhibit enormous variation across groups.”

Now, unlike the incest case, there isn’t one strong adaptation behind the scenes (sexual disgust) creating different payoffs for the different regimes.12 More or less, people don’t care too much about which regime they are in, though they don’t want too many food taboos, each of which puts some limit on getting calories and nutrition. So the Menu Game is similar to the Incest Game in that it’s once again a coordination game, but there is no strong magnet pulling the result to a particular equilibrium. From this, we can explain why it is that moral rules surrounding food are so variable, unlike the incest taboo. You’re seeing the result of a coordination game, but one without a strong equilibrium selection process. When this game is being played, the contents of the rules might appear relatively arbitrary because there is no attractor, allowing many different equilibria to be reached. No pigs, lots of fish, this food can’t be paired with that one… In a stroke, we have explained why food morality is variable while incest morality is (nearly) universal. As a general matter, this view suggests that whatever people find disgusting (in virtue of adaptations designed to reduce contamination) will gain an advantage in terms of equilibrium selection.

These games explain why there is such diversity across cultures in rules. The details of clothing, profanity, art forms, food combinations and much else often don’t affect one’s payoffs—tangible outcomes—in the way that rules about sex, money, and harm do. So there’s no strong equilibrium selection and cultures wind up with varied moral equilibria. This pattern is not that different from our cicada friends. The benefit to emerging at the same time as others explains why they all clump together. But there are also different options—13 years, 17 years, etc.—so different species wind up at a different interval.

Now, getting more complex, some moral contents are like the Battle of the Sexes game. The equilibrium you prefer depends on various details of your life. This is just like other asymmetrical games, such as the Pass Defense Game we saw in Coordination 2.

Let’s take a rule about property rights, linking back to our butterfly friends who we saw playing the Bourgeois strategy in the first post in this series. Moral rules emerge as technologies change. I’m old enough to remember when Napster forced everyone to think about the details of what rights a music producer had over their creation. If I copy your song—but the song still exists on your server—have I committed a wrong?

One rule you might have is that songs created by artists are their property and, therefore, it is wrong to use them without paying. Another rule you might have is along the lines that information should be free, so creators may not protect their music: they must share. Brad, the creator of music has, obviously, a strong preference for the regime in which he can sell what he makes, reflected in his big payoff for the “don’t steal” regime. Alex, the consumer, prefers the regime in which he can enjoy Brad’s music without the bother of paying for it.

This game creates fights over what moral regime will reign supreme. Here in the U.S., we wound up in the upper left because in this case the equilibrium—the law—was selected by the relevant legal authorities in a free market system, which tends to value property rights. Still, there is ongoing conflict over the details. The key point is that when interests differ, we should expect fights over the contents of the moral rule. I (in collaboration with Jason Weeden) have argued that the best place to look to understand these fights is to identify the players’ interests, though this too remains a point of debate.

Notice that these games explain a great deal about moral contents. It’s very easy to get to the don’t-do-that equilibrium for things people don’t want to do, which is why we wind up with laws against bestiality, suicide, and so forth. Further, even though some rules are going to have detrimental effects—preventing you from eating stuff you’d like to, say—the benefits of coordination might be large, leading to a fluorescence of rules, some of which are net detrimental to the groups that adopt them.

Such is the result of coordination games.

Summary of Games

Let’s sum up the games.

In Incest style games, because of anti-incest adaptations, people choose the equilibrium in which the thing they don’t want to do anyway is prohibited. This process leads to cross-cultural similarities. A lot of disgusting stuff is in here.

In Menu style games, people don’t have very strong preferences. Everything else equal, they would prefer fewer foods be banned. Still, they don’t care all that much about whether eating fish on Friday is prohibited or required. This process generates cross-cultural variability. A lot of relatively arbitrary stuff is in here.

In Musical Rights style games, different people in the group have different preferences about which equilibrium is selected. This leads to conflict. This game is where you are likely to see the most fighting over the rules and significant cross-cultural variation. These fights are often about issues in which people’s interests are in conflict: sex, money, and power. In these cases, the rules really matter.

The careful reader will notice that in this discussion of morality I’ve left out a discussion of harm and cooperation. That might seem odd. Both have been discussed as closely, even intimately, related to morality. I’ll address them in a future post but, for the moment, I only ask if this analysis seems to explain the broad features of moral rules.

Conclusion

Let’s use the same five-point summary I’ve been using throughout these posts on coordination games.

The reason that people want to agree on rules is that they are solving a coordination problem.

The reason that different cultures have different rules is there are multiple equilibria. There are a vast number of rules about what is prohibited, required, or optional, across the domains of human behavior.

There are similarities among moral rules, often because there are equilibrium selection forces that result in similar outcomes. Prohibitions against incest are common because those norms have a tremendous advantage in equilibrium selection because of sexual disgust.

There can be ongoing conflict about equilibria, often because some equilibria are better than others for some players. Which equilibrium is selected has to do with the details of the game and the interests of the players. Property rights provide a good example.

Meanwhile, the explanation for why humans have moral rules has to do with… something important. The post on hiking, coming soon, will explore this in more detail.

Optional Postscript: What is the Selection Process?

This material is a bit technical. It’s optional in the sense that you don’t need to work through these ideas to understand the overall approach in this post.

In any case, throughout these discussions, I’ve alluded to an equilibrium selection process. How does that work?

The answer to that could fill a book, or even many books, because in many ways that is really a question about how culture works. How are ideas born, how do they spread, and how do they die? I’m not going to be able to answer those questions because they are incredibly complicated and tremendous debate remains about them.

So in this tiny section, which can’t really do justice to the issue, I’ll just sketch a few ideas. As a general matter, there is some great scholarship on how cultural transmission works; I’ve put recommendations below in a subsection of the references. This section is intended more for our readers in the social sciences than our more general audience, so proceed with caution.

Ok, one way that ideas change over time is through a process that Rob Boyd and collaborators have dubbed cultural group selection. The key premise of cultural group selection is that groups with certain cultural practices can have a competitive advantage over other groups, leading to the spread of those practices through a process analogous to biological selection. These advantages might arise, for instance, from cultural traits that enhance the ability to organize resources effectively. You can think of these traits—rules that require prosocial behavior, for instance—as equilibria with higher values, as we saw in the firefly case. As groups interact, compete, and sometimes conflict, those with more adaptive cultural traits—better equilibria—are more likely to thrive, expand, and pass these traits on to future generations, either through direct cultural transmission, conquest, or by serving as models for other groups to emulate.

So, one group, say, has a rule that says “you cannot charge interest.” Another group has no such rule. Because charging interest is so useful—moving capital to better uses—the group that allows it prospers and the idea spreads. That is one way that equilibria can be selected, by differential success of groups.

A second way is related to the discussion of incest. Humans have a rich evolved psychology that guides their own behavior when it comes to mating, sex, hunting, gathering, exchanging, reciprocating, and so on. These rich evolved systems—some call them modules—create preferences. The aversion to incest creates a preference for the taboo against it. More generally, anything that evokes disgust will be more likely to be the subject of a taboo or prohibition. Fear of physical harm helps give harm-based rules a boost, as we’ll see in a future post. Our penchant for exchange helps anti-cheater rules and probably those to do with proportionality and ownership. And so on. This is where work by those who have built ways to organize moral contents, such as Haidt and Curry, intersects with the ideas described here. The psychological systems they discuss, including disgust, cheater-detection, and so on, contribute in important ways to the process by which some rules win and some fall away.

So, if we assume that new moral rules are continuously being proposed—see, for instance, Paul Rozin’s work on moralization—then one selection process is the support or resistance that people in a group mount for different candidate rules. Innate psychology, including the emotions and systems for exchange, fills the payoff of the coordination games, pushing equilibrium selection around.

In addition, there are processes at work that influence the adoption of various sorts of cultural beliefs, not just moral rules. People tend to imitate what high status people are up to, a process called prestige-biased transmission. Often, observers will try to match what they think most other people do or think, called norm-based conformity. These processes, studied by anthropologists, are, in a word, complex, but might help explain how ideas spread.

Finally, humans have organized themselves in the modern world and created a whole set of equilibrium selection strategies. Some groups are dictatorships and when the dictator chooses the rules, people enforce them. Some groups have chosen representative democracy, holding elections—with specific rules—to choose people to govern. Humans have created rules (elections) to choose people who make rules (laws), some of which are, of course, about how to create rules (e.g., administrative law, my fave).

And so it goes.

REFERENCES

Atran, S., & Norenzayan, A. (2004). Religion's evolutionary landscape: Counterintuition, commitment, compassion, communion. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27(6), 713-770.

Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (1985). Culture and the Evolutionary Process. University of Chicago Press.

Henrich, J., & Gil-White, F. J. (2001). The evolution of prestige: Freely conferred deference as a mechanism for enhancing the benefits of cultural transmission. Evolution and human behavior, 22(3), 165-196.

Henrich, J. (2015). The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. Princeton University Press.

Henrich, J., & Boyd, R. (1998). The evolution of conformist transmission and the emergence of between-group differences. Evolution and human behavior, 19(4), 215-241.

Mikhail, J. (2009). Is the prohibition of homicide universal-evidence from comparative criminal law. Brook. L. Rev., 75, 497.

Tomasello, M., Krupenye, C., & Hare, B. (2017). Great apes understand others' intentional actions. Psychological Science, 28(4), 412-418.

Sperber, D., & Hirschfeld, L. A. (2004). The cognitive foundations of cultural stability and diversity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(1), 40-46.

Sperber, D. (1996). Explaining Culture: A Naturalistic Approach. Blackwell.

Other References

Brown, D. (1991). Human universals. Temple University Press.

Curry, O. S. (2016). Morality as cooperation: A problem-centred approach. In T. K. Shackelford & R. D. Hansen (Eds.), The evolution of morality (pp. 27–51). Springer International Publishing AG.

Curry, O. S., Mullins, D. A., & Whitehouse, H. (2019). Is it good to cooperate? Testing the theory of morality-as-cooperation in 60 societies. Current anthropology, 60(1), 47-69.

DeScioli, P., Gilbert, S. S., & Kurzban, R. (2012). Indelible victims and persistent punishers in moral cognition. Psychological Inquiry, 23(2), 143–149.

Fessler, D., & Navarrete, C. D. (2003). Meat is good to taboo: Dietary proscriptions as a product of the interaction of psychological mechanisms and social processes. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 3(1), 1-40.

Gray, K. & Kubin, E. (in press). Victimhood The most powerful force in morality and politics. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology.

Gray, K., Young, L., & Waytz, A. (2012). Mind perception is the essence of morality. Psychological Inquiry, 23(2), 101-124.

Greene, J. D. (2013). Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them. Penguin Press.

Haidt, J. (2012). The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Pantheon Books.

Mikhail, J. (2007). Universal Moral Grammar: Theory, Evidence, and the Future. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 143-152.

Petersen, M. B., Sznycer, D., Sell, A., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2013). The ancestral logic of politics: Upper-body strength regulates men’s assertion of self-interest over economic redistribution. Psychological science, 24(7), 1098-1103.

Rozin, P. (1999). The process of moralization. Psychological science, 10(3), 218-221.

Schein, C., & Gray, K. (2018). The Theory of Dyadic Morality: Reinventing Moral Judgment by Redefining Harm. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(1), 32-70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868317698288

Sell, A., Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2009). Formidability and the logic of human anger. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(35), 15073-15078.

Sell, A., Eisner, M., & Ribeaud, D. (2016). Bargaining power and adolescent aggression: The role of fighting ability, coalitional strength, and mate value. Evolution and Human Behavior, 37(2), 105-116.

Tomasello, M., & Vaish, A. (2013). Origins of human cooperation and morality. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 231-255.

Wheeler MA, McGrath MJ, Haslam N (2019) Twentieth century morality: The rise and fall of moral concepts from 1900 to 2007. PLoS ONE 14(2): e0212267. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212267

Please see the post on the definition of morality in The Boneyard. By “morality,” I’m not taking about what is virtuous—as in, “John is a moral person,”—or what we value. I’m just talking about moral judgments about wrongness, sin, etc.

Here and below, bold font is my emphasis.

In A Companion to Moral Anthropology, D. Fassin (Ed.) 2012, p. 89. Relativism and Universalism

Nelson, S. (1980) Factors influencing young children’s use of motives and outcomes as moral criteria. Child Dev. 51, 823–829

Bybee, J. and Fleischman, S., eds (1995) Modality in Grammar and Discourse, John Benjamins

Mikhail, J. (2002) Law, science, and morality: a review of Richard Posner’s ‘The Problematics of Moral and Legal Theory’. Stanford Law Rev. 54, 1057–1127.

Mikhail, J. (2009), p. 510.

Quoted in Wolf A. P. (2014). Incest avoidance and the incest taboos: Two aspects of human nature.

Wolf, A. P. (2014). Incest Avoidance and the Incest Taboos: Two Aspects of Human Nature

A key difference in this post is that I haven’t told you what the advantage of coordinating is. In the post about sports, I explained that the gain was from the motive to measure relative ability. The next post addresses this. If you can’t wait to learn what game is, the idea is developed in DeScioli & Kurzban, A Solution to the Mysteries of Morality.

Well, this might not be exactly true. Fessler and Navarette also point out that meat is the subject of taboo more than other foods, suggesting that this is because “natural selection has produced an ambivalence toward meat such that, compared to other foods, meat is more likely to become the target of disgust” (p. 2). Sort of. The reason is that the disgust for some foods—many animal parts, no doubt—makes the equilibrium in which it is prohibited just fine with many people, giving it a boost.

GM, dr. Kurzban. Great job as usual, but i have aquestion.

I don't get why you say "menu taboo" are "choice free": choosing a food instead of another is quite an important problem for an individual.

E.g. a nomad herder depends on his herd's milk to survive (e.g. Fulani children drink 5 liter a day only untill 3 y.o.) so the Aryan developed the taboo about cow slaughtering; pigs in hot climate suffers a lot of tapeworm, so semitic people developed the pork taboo.

Maybe you should appear in The Dissenter... (the podcast)