Ariel, the Little Mermaid, had to try to win Eric’s heart—and true love’s kiss—without talking. This was the deal that she made with Ursula: for the gift of transforming from mermaid to human, Ariel surrendered her voice for the three days of courtship. If she could succeed in her suit, she would get her voice back. In the scene in which the deal is being done, Ariel asks Ursula how she can woo Eric without speaking. Ursula, in an un-Disneylike answer, alludes to her looks, pretty face and body language, the last with a suggestive hip move.

Mating, like so much of human social behavior, can be understood as a game. In the human world, for most of human history, individuals of one sex competed for the best mates of the other sex. In this game, each side, if you will, had an array of tools to deploy. Men, competing with other men, signal traits, including those that indicate an ability and interest in investing, as Geoffrey Miller discusses in his excellent book, The Mating Mind. Women, on the other hand, face a sex that cares more than they do about physical appearance and, therefore, use that arrow in their quiver to best effect.

Both sexes, it should be understood, care most about finding someone who is kind and understanding, as David Buss has shown in his many years of research on the topic.

Still, the sexes do differ and they will use whatever strategies are available to win the mating game as best they can which means, as Steve Pinker put it, finding “the best-looking, richest, smartest, funniest, kindest person who would settle for you.”1

Unless, of course, one or more of their tools has been stripped from them by a magical octopus.

Or social norms.

The Games People Play

From the standpoint of psychology, understanding people’s behavior often means figuring out what game they are playing, which isn’t always obvious. However, once you identify the game, otherwise mysterious choices become easier to explain. For example, at first glance, it might appear as if protestors are playing a game in which they deeply care about changing political policy. But then you might be bewildered by the fact they know nothing about what they’re protesting. Their ignorance becomes comprehensible when you consider a different game, involving social benefits from sending certain kinds of signals about being virtuous. Similarly, if you understand that morality is a coordination game, you can understand why many moral rules make everyone worse off.

Framing social interactions as a game can also help develop new strategies.

I currently have friends on the mating market and many of them complain that people with whom they arrange a date cancel with very short notice, often for unsatisfying reasons or for no reason at all.

In certain respects, going on a date is a coordination problem. The date is only a date if the two people are at the same place at the same time.

A problem, however, arises because when two people on Tinder agree to meet at The Corner Diner on Friday at eight, those messages are, as an economist would say, cheap talk. It’s easy to say you’ll be there, but nothing physically prevents you from flaking. This possibility presents a problem because each person, knowing the other person might flake, is more inclined to do so themselves, especially if a better option comes along.2

Now back in my day—tell us a story, grandpa—there was a solution to this problem. Cancelling on short notice just wasn’t done. Barring a medical emergency, if you canceled within a couple days, let alone hours, of the date—or just stood the other person up—you were the bad guy. Cancelling was moralized: canceling violated a moral norm and not to be done by any reasonable person. For reasons that surpass my limited capacity for understanding, this moral norm has eroded and flaking at the last minute now carries little if any moral weight.

This fact has led to a kind of spiral. If you live in a world in which many people flake, then you have a number of counter-strategies if you really don’t want to be without plans on Friday night. For one thing, you can double book, making two dates at that time, doubling the chances that one of your potential partners will actually keep the date. Of course, knowing that others double-book, there is an incentive to use a similar strategy or even a more robust one, triple booking, to counter, and on it goes. You might also try making the date more appealing by offering a more expensive restaurant than The Corner Diner. There are, of course, any number of counter-moves.

One solution to certain kinds of coordination problems is commitment. If you and I can credibly commit to being at the agreed place, the problem is solved. Seeing the problem of dating as a coordination game inspired me to create Bondzy. This app allows users to post bonds that are forfeit if the user does not appear at the designated place at the designated time. If I post a Bondzy, then you know—or, at least, you are more likely to believe—that I’ll be there when I say I will. Knowing how commitment solves coordination problems facilitated a technological fix. (Stickk uses a similar idea.)

This post is not, however, a shameless plug for Bondzy.

This post is a meditation on how moral rules can be used to gain strategic advantage in the games people play.

In many contexts, new strategies beget counter-strategies. Against the long bow, you deploy soldiers with plate armor or fast cavalry to close the distance to archers before they can fire off a lot of volleys. Against fast cavalry, you dig ditches or arm troops with pikes. Today, we are witnessing the race to discover effective counters to drones, which will inevitably lead to counters to those counters. And so it goes.

Having said that, there are cases in which there is no effective counter. Take the case of chemical weapons used in warfare. These weapons produce extreme pain and, importantly, are difficult to counter because they are somewhat indiscriminate, spread by wind and moving water. In part for this reason, nearly all nations have signed on to the Chemical Weapons Convention. This agreement, which took effect in 1997, bans the production and use of chemical weapons. There is, of course, nothing that makes it impossible to use chemical weapons. Instead, the Convention—a coordination device—declares that using chemical weapons simply isn’t done. The convention, known to all, is akin to moralizing their use. If you do it, then everyone—in this case, the world—sides against you.3

Laws function in the same way, formally taking away strategies with the backing of the force of the state. Elsewhere I’ve discussed how wealthy politicians in Venice protected their power: banning the type of contract that supported their own rise. When you have the power to use bans, why go to the trouble of using a counter-strategy? It would be a mistake to think that using rules—the law, in the case of economics—to suppress competition ended in the 14th century. For example, if you want to be a florist in Louisiana, you can’t just open up a shop. Instead, to protect the existing florists, there is a written test, fees, and each shop must have a licensed florist working 32 hours per week or more. These laws are good news for existing licensed florists. Bad news for market entrants.4

To take another example, when Uber was working to create cheaper ways for people to get around, the (heavily regulated) taxi industry in various cities, instead of working to reduce rates and improve service, lobbied to get these transportation network carriers banned. Then as the taxi drivers slowly lost the battle, they retreated to trying to protect only the most lucrative routes, like the airport. In most municipalities in the U.S., this gambit eventually failed. As a general matter, in industries where the regulators have been “captured,” administrative law can be used to keep competitors out when they develop an innovative strategy that threatens existing dominant firms.

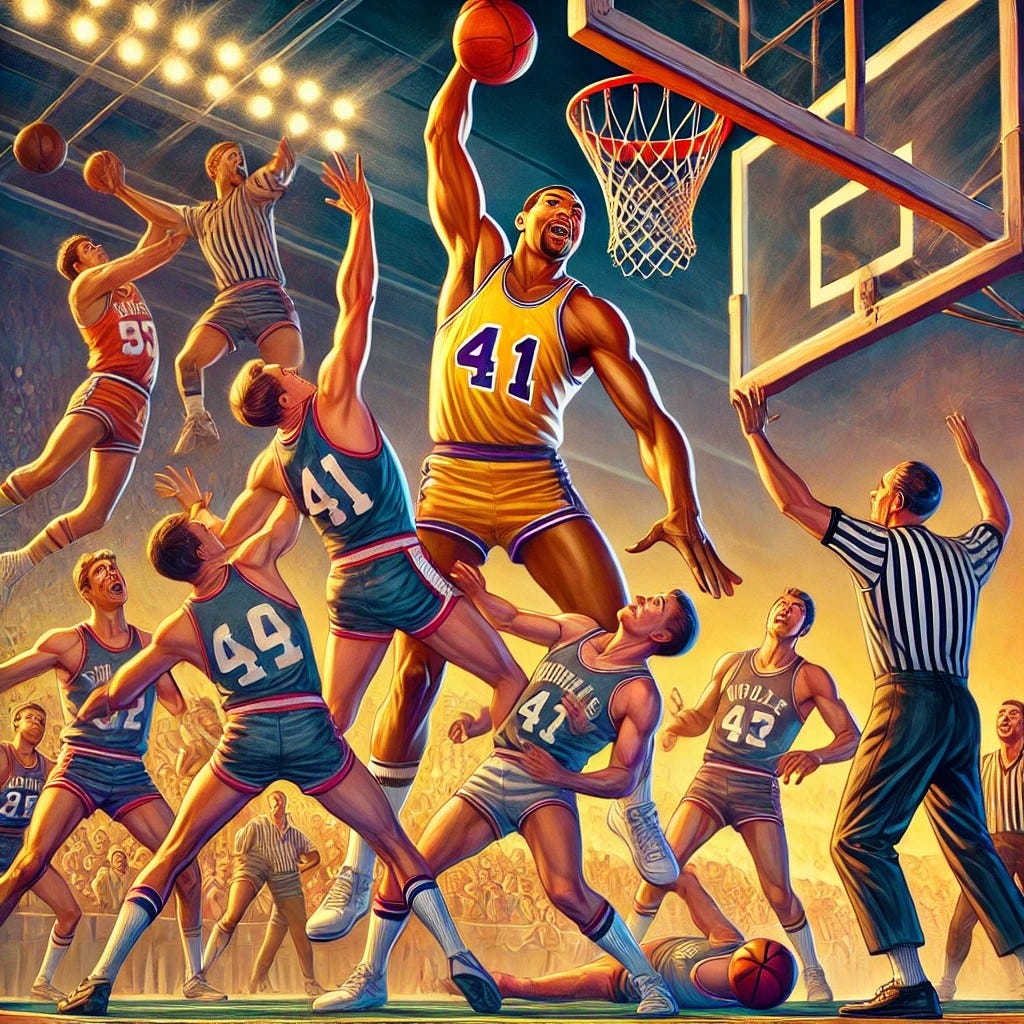

Moving to sports, when Wilt Chamberlain was dominating the National Basketball Association, teams realized they could implement a new strategy against him. Rather than try to play normal defense and get dominated by Chamberlain, they just fouled him intentionally in order to get him to shoot from the foul line—where he wasn’t very good. The strategy worked and was hard to counter, resulting in a game that was much less fun to watch. The league changed the rules surrounding free throws, effectively banning this counter-strategy.

The key point is that against strategies, you can either develop a counter-strategy or try to counter the strategy with a moral rule, enforced by the power of social norms, the power of NBA referees, or the power of the law. This logic applies to the games people play whether military, economic, athletic, political, or social.

Mating Games

To return to Ariel, David Buss has pointed out over the last several decades that differences between men and women have led to robust evolved sex differences in terms of what each sex prefers in a mate. In addition to men and women having different preferences, they also have different strategies to accomplish their mating goals. The balance of this piece is a look at how different moral rules can affect men’s and women’s strategies as they pursue their mating goals. In some cases, these moral rules are more or less obvious, but in one’s own culture they can be more difficult to notice, as moral norms become so familiar they seem less like counterstrategies and more like simple moral truths.

Consider, in this context, apartheid-era South Africa. The Immorality Act of 1927, amended in 1950 and 1957, prohibited sexual relationships and marriages between white people and people of other races. The Act was not, however, enforced uniformly. White men having sex with non-white (or, really, non-European) women was often overlooked—and when it did occur, the woman was punished more severely than the man. In contrast, black men having sex with white women was not. As Hazan recently put it, “Uncontrolled sexuality in colonies, especially that which involved white women and local men, was exceedingly dangerous… White women’s sexuality needed to be reserved for white men…” The Act illustrates how laws, combined with the selective enforcement of the rules by those in power, were used by white men to achieve their strategic mating goals.

More broadly, because men’s and women’s preferences and strategies differ, the cultural rules—both those set into law and those enforced in virtue of shared moral norms—can favor one sex or the other. This fact, plus the forgoing discussion, sets the table for the idea that people who are in a position to influence the rules should be expected to favor and propagate rules that advance their interests, using these rules in a way that parallels the examples above.

Take, for simplicity, the apocryphal story to the effect that William James penned the following insight about sexual strategies:

Hogamous, Higamous,

Man is polygamous,

Higamous, Hogamous,

Woman is monagamous.

Whether the story is true or not, it reflects the basic idea that the sex with little gametes and lower obligate parental investment will be selected to pursue multiple matings while the sex with big gametes and high obligate parental investment will be selected to seek one mate to invest in offspring. (For much more detail, see The Evolution of Desire by David Buss.)

Now, suppose you are a powerful male in a culture and you play a role in creating the rules. Given your strategy, you might want to make polygamy not only allowed, but virtuous. You could go still further, making it obligatory. It’s important to note that this regime doesn’t benefit all males. If we assume sex balance, then where there is polygamy there are some who go without a mate as a mathematical certainty. Enforced polygamy helps males at the top.

From the female perspective, this rule might work either for or against her interests. In classical polygyny threshold models, a female—usually a bird—is faced with a choice of becoming the second mate of a high value mated male or the first (and only) mate of a lower quality male. Under strict monogamy, a female would have this choice taken away and would be forced to mate with the lower quality male. On the other hand, the enforcement of monogamy confers benefits to females, reducing the chance of the diversion of resources. The key point is that rules affect different sexes—and different people—in complex ways.

Drawing on Buss’ work on sexual strategies, and speaking very broadly, consider the differences in preferences and strategies between men and women. Keep in mind, this is simplifying, so have a look at the linked paper for more precise exposition.

In terms of preferences, women for sure want the ability to choose their mate. This choice is as important as anything in the context of mating. As indicated above, she would like a world in which she—and her offspring—receive investment from her partner, a preference which is often facilitated with a monogamy norm, lest their partner divert resources to attracting a second mate. Broadly, she would like to be able to choose high status (often older) men. And to fulfill these preferences, she would like to be able to signal to potential mates those features they themselves value. This often, but not always, will entail signaling one’s physical characteristics.

What norms would inhibit these strategies and preferences? First and foremost would be a norm that takes the power to choose away from women. This would be the case when marriages are arranged by, say, the woman’s—or, often, the girl’s—family.5 Second, as we have seen, polygamy might be a benefit under certain circumstances, but enforced monogamy might well do more to advance women’s interests by reducing diversion of investment. Third, if a woman does manage to find herself in a culture in which she is accorded choice of mates, then for at least some women, losing the opportunity to signal the features potential mates are interested in would undermine their strategy.

It can be seen that certain moral regimes, with rules and norms enforced whether by the broader society or instruments of state, might work very heavily against the strategies women would like to use. You can imagine that powerful men able to make rules might respond to female preferences by, say, making themselves appealing as mates, committing to investment, and so forth, to counter the female strategy by making themselves likely to be chosen at mates. Instead, just as in the above cases, moral rules are deployed to undermine women’s strategies, removing the need to make these efforts. Rules are used instead.

One could imagine a moral regime that worked in the opposite way, using rules to check male strategies. You could imagine that monogamy and parental investment was strictly enforced, both by norm and by law. (For instance, no polygyny, men must invest in children even if the relationship ends, etc.) You could have rules that check men’s ability to deploy the features that women prefer—status, for example—in a way that parallels prohibitions on dress. You could imagine rules that sharply punish the pursuit of multiple partners, the signature male strategy.

“Morality” has a strangely untouchable reputation. I suspect the reason is that people confuse “morality” as a synonym for “cooperation,” and who doesn’t like cooperation?

Cases like the ones discussed here show another facet of morality’s other, less felicitous side.

If you can’t beat ‘em, ban ‘em.

See p. 417, How the Mind Works.

In discussing this post with others, it came to my attention that some people feel that one sex is more likely to cancel than the other. I know of no data on this but if someone can direct my attention to a relevant dataset, I would be grateful.

Of course this isn’t a perfect solution, as the instances of the use of chemical weapons illustrates. Still, it’s fair to say their use has been very rare since the Convention took effect.

Consider, for example, the story in this piece: Firoza, 18, was in the 11th grade when the Taliban shut her school in Ghor, destroying her plans of entering a university. Soon her family married her off against her will. "The wedding crushed all my dreams," she said. "I faced immense pressure and had no option but to accept a forced marriage.”

Regarding the chemical weapons thing: I read once (I believe from Bret Devereaux at ACOUP -- who is a military historian, but not of the relevant time period) that many nations' being signed onto the Convention is somewhat of an empty gesture because, for those signatories, chemical weapons are usually not tactically or strategically valuable -- the fact that the damage is indiscriminate and spread around by wind makes them incompatible with fast, mobile, combined arms warfare (you might use them and then run your advancing army into them), which is basically standard doctrine for all the powerful militaries in the world today. So there are only a very few instances where using them might make sense from an amoral military perspective anyway -- such as when you lack an adequate standing army and your enemy is far away -- that the most influential signatories are very unlikely to ever find themselves in. (Then, of course, those signatories can incentivize signing on even for states like Assadist Syria that may have greater use for them in moments of crisis.) So I would be a bit more skeptical that the Convention solves the problem you're talking about there in the way you suggest.

Anyway, just thought this bit of trivia may be interesting!

I have used Tinder quite extensively for several years and indeed double-booked any time I had the chance, though I'm not aware of others who did the same. Not even once I had both women show up, forcing me to flake on one of them.

Not presenting this as a data point. Just sharing something to have a sad laugh about.