How to Understand Human Behavior (Part 2/3)

Every situation is a piece of cake.

In Part I, I explored the deceptively simple idea that human behavior is a function of a person in their situation. I argued there was more meat on those plain bones—person and situation—than might first appear, and began poking into what a person is. In this post, I’ll turn to the other half of the equation—the situation—which is usually the more predictive factor.

Let’s revisit a line from the end of Part I: “Each of us can be understood as a human in a particular situation, with a history of particular situations.”

That history is twofold:

Our species’ history. Every organism, in its current form, is the byproduct of countless exchanges between earlier versions of itself and earlier versions of its environment. This long record of situations and their outcomes is what sculpted the Homo Sapien of today. Had our ancestors evolved in air with twice as much oxygen and half as much nitrogen, our lungs would be built differently—and so would our response to thin air.

Our personal history. A shorter record of situations unique to each life. “Individual differences,” as Tooby and Cosmides (1990) write, “arise from exposing the same human nature to different environmental inputs” (p. 23). Along with the randomness of sexual recombination and development, this is what makes each of us singular.1

Every moment, we bring both histories to bear: one encoded in our design, the other in our experience. Which is more powerful? The first, by far—for the same reason that a study with a large sample size carries more weight than one with a small. You, precious reader, have had far fewer experiences than our species has. You might count on your fingers and toes how many genuine moments of awe you’ve known, but our species has known billions of them.

Over time, those innumerable encounters with the extraordinary shaped an “awe organ” that each of our personal experiences merely fine-tunes. As Tooby and Cosmides (1999) write, “The function of developmental mechanisms is to (a) successfully construct the species-typical functional design and (b) calibrate [it]…so that it is adaptively tailored to the local conditions it will face” (p. 459). The difference between the two can be thought of as the difference between installing an HVAC system and adjusting the thermostat. The former is a response to consistent seasonal variation in temperature; the latter, to daily fluctuations.

Let’s simplify matters and, at the same time, stoke your appetite. The situation can be imagined as a three-layer cake. The bottom layer is our ancestral past, which molded our basic design; the middle is our personal past, which modified that design; the top is the present moment. As with most cakes, the base layer is the most substantial, but the upper layers get all the attention.

The cake analogy makes certain findings unsurprising. Consider the following from Jens Ludwig’s Unforgiving Places, which we encountered in Part I: “What matters most [for gun violence] is not so much the neighborhood in which a person grows up but rather their contemporaneous neighborhood environment.”2

In evolutionary terms, the same is true at a different scale: how we learned to navigate situations as a species far outweighs how we learned to handle them as individuals. For any given detail of a current situation, what usually matters most is the role it played in our evolutionary history, not in our own lives. However, we tend to focus on exceptions to this rule—like Pat Solitano in Silver Linings Playbook, for whom a particular song recalls his wife’s infidelity—because the more powerful situational cues, in being universal, are easy to overlook. These include darkness, sudden noises, angry postures, eerie silences, and so on. These are apersonal; they mattered long before you and I did.

The social scientist Adolphe Quetelet once wrote: “Society prepares the crime and the guilty is only the instrument by which it is accomplished.” Given everything above, we might say something similar about human behavior: Our species’ long history with recurring situations prepares the behavior and the individual is merely the slightly unique instrument through which it is carried out.

This makes the details of the situation incredibly important.

Jealous Much?

To ground our investigation of the details of a situation, let’s imagine someone worried that their partner is cheating—someone in the throes of sexual jealousy. How did our subject come to feel this way? By noticing and interpreting cues that, over evolutionary time, proved useful for retaining a mate—duh!

Like every emotion, sexual jealousy measures information and motivates action that helped our ancestors survive and reproduce. The same goes for anger, lust, gratitude, fear, curiosity, and so on.

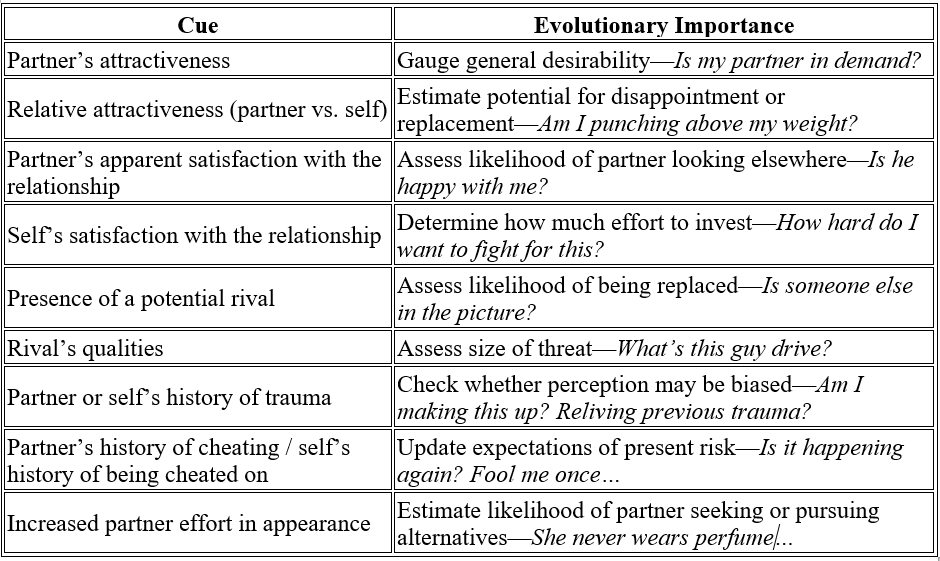

Here is an incomplete list of what our jealous subject might be measuring:

The list could go on and on. As Tooby and Cosmides (1990) note: “Any feature of the world—either of the environment, or of one’s own individual characteristics—that influences the achievement of the relevant goal state [in this case, mate retention] may be assessed by an adaptively designed system” (p. 59). That includes information only tangentially related to jealousy, such as timing. Do suspicions unfold over months, or does our subject come home, as Pat Solitano did, to find his wife in the shower with the history teacher?3

Even a full list of cues, however, would still tell us little about how they shape behavior.4 We’d still need to ask:

How has personal experience modified our subject’s species-typical design?

In what ways might the modern world be confusing their Stone Age mind?5

Is there anything that their desire to maintain the relationship is competing with?

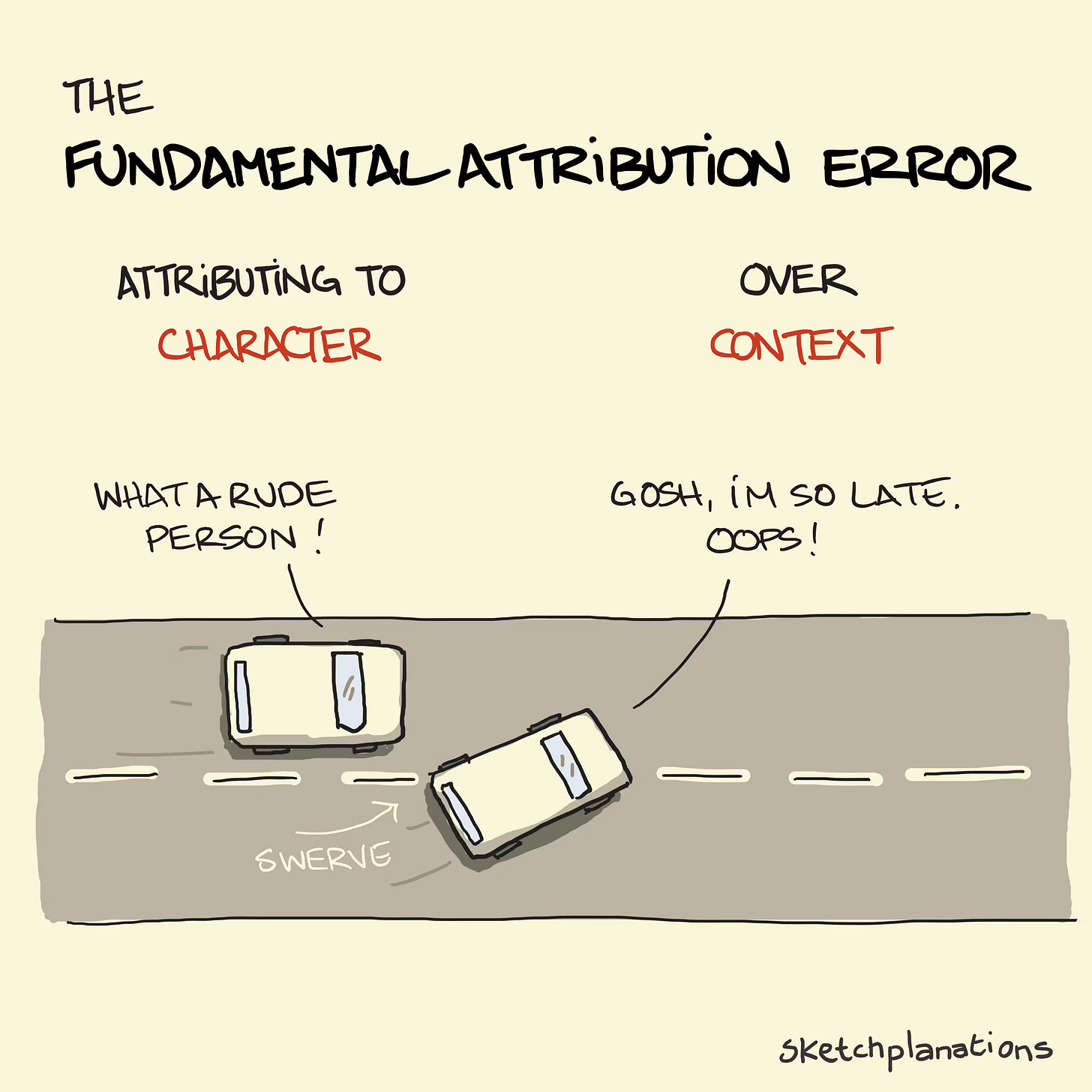

Let’s start with the first. Who, pray tell, will observe the observer? Actually, plenty of people. As I noted in Part I, the social sciences—especially the helping professions—are often too eager to analyze the person analyzing the situation, which leads to all kinds of fundamental attribution errors.

In fact, it’s hardly an exaggeration to say that psychotherapy’s legacy has been to overemphasize personal details at the expense of situational ones. This leads to intolerable phrases such as “every person is different” or “it depends.” It motivates books such as Every Person’s Life Is Worth a Novel. I judge these as sweet sentiments that in many cases undermine the endeavor to alleviate human suffering, which could benefit greatly from acknowledging a shared human nature.

As for the second question, it’s time for my usual reminder: the situation today is not what it once was. Since the Industrial Revolution, technological and social change have multiplied and transformed the opportunities for infidelity. Co-ed workplaces, increased travel, pornography, dating apps—each adds a new point of contact with potential mates. In countless ways, the ancient link between a cue and its importance has been disturbed—not only for sexual jealousy, but for nearly every emotion and sensation.

Other Competing Considerations (Like Culture)

Attentive readers might have noticed something peculiar in the table above: not every cue reflects information that would have benefited mate retention in the ancestral past. Compare “partner’s attractiveness,” “self’s history of being cheated on,” and “partner’s history of trauma.” The first has a clear evolutionary lineage as a suspicion worth attending to; the second is an adaptive calibration of risk based on experience; the third is just an idea that some of us living in America in 2025, heavily influenced by therapy speak, happen to believe.

All three time zones are in play—the deep past, the personal past, and the present—but only the first two are useful here. By contrast, the modern notion that a history of trauma raises the odds of cheating is likely to mislead. First, the evidence is thin and inconsistent.6 Second, even if a small effect exists, attending to it may distract from simpler explanations.

Consider a recent New York Times advice column responding to a reader whose partner had cheated twice. “In my experience,” the columnist wrote, “people who cheat are often acting out their own issues, not their feelings about their partner.” Huh? Surely those who feel good about their relationship cheat less than those who feel bad or mixed. Personal issues such as trauma might play a role, but it’s hardly where I’d start my investigation, whether as therapist, betrayed partner, or cheater. Not every behavior filtered through the trauma lens becomes more intelligible, you know.

Meanwhile, where did this idea come from? Academia. For decades, the academy has been a hatchery for well-intentioned but largely braindead theories, some of which have migrated into mainstream Western thought. (See Rob’s It’s All Academic for the incentives driving this.)

The deeper question is why such ideas persist. They often run counter to intuition, experience, and eventually to the science itself. (Many begin as scientific findings, go on to be disproven or unreplicated, and enjoy a long life in the public domain nevertheless—see the power pose.) The proximate reason for this persistence is authority: academics are supposed to be the keepers of truth. The ultimate reason is conformity: once an idea becomes a cultural truth, there is pressure to accept it. If the idea is wrong, then we must be wrong to belong.

Culture, in other words, is and always has been part of the environment—like air, trees, and germs—and therefore represents a persistent and pervasive factor in every situation. Our jealous person wants to maintain their relationship and their status as a member of the tribe, but sometimes this is a tough needle to thread—just as it would be difficult to tail a partner for six hours without eating or peeing. Humans have many priorities; sometimes they compete.

The current anthropological view of culture, which has seeped into everyday Western thought, is similar to the traditional human view of humans. By and large, anthropologists have been obsessed with differences between cultures and largely blind to the fact that every human society has it, or that every individual has the mental architecture to parse it. Cultures differ, of course, but the human capacity to learn and generally follow cultural rules does not. In the same way, the fact that people see different things or speak different languages does not mean that eyes or the capacity for language aren’t universal human traits.7

That said, there’s an important difference between culture and vision: cultural beliefs lead us astray in our assessment of reality far more often than vision does. Few people in the ancestral environment were creating and mass-producing visual illusions, but they were certainly producing the delusions of culture: myth, groups, religion, morality. Culture is a feature of the environment, then, much like visual data—only far less trustworthy.

So, people interpret their situations through evolved intuitions (partner attractiveness), personal experience (history of being cheated on), and competing priorities (the need to pee, the importance of following cultural scripts). Some of these lead to an accurate grasp of what’s going on and prompt adaptive behavior; others distort it and lead us astray. Culture is a particularly unreliable source of information because, while it is as old as humanity, its expressions change frequently and drastically. For most of human history, on the other hand, a rose has been a rose has been a rose.

The Culture of Clinical Psychology

Speaking of culture’s ability to mislead: has clinical psychology, by and large, done more to improve or undermine the average person’s understanding of their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors? I hope my answer is clear by now; otherwise I’ve spent 2.5 years writing into an abyss.

Consider this very long, very worthwhile passage from Tooby and Cosmides (1990):

Imagine, for example, a man whose attractiveness on the “marriage market” is lower than his wife’s. This enduring personal situation may lower his sexual jealousy mental organ’s threshold of activation, so that his mental organ will be activated with less confirmatory data than others require. Consequently, he will become jealous more easily, and therefore more often, than other men. His jealousy may even appear situationally inappropriate or “irrational,” in the sense that his wife is faithful, devoted, and attempts to reassure him. Nevertheless, hundreds of thousands of parallel ancestral situations will select for a mental organ that is responsive to the average outcome of such situations, and his mental organ may handle different cues separately…If, over thousands of generations, reassurances from one’s spouse did not reliably predict his or her long-term fidelity, but an inequality in desirability was reliably associated with an increased risk of infidelity, then natural selection would have designed a mechanism that responds to inequality in desirability, and not to reassurances. Although in any individual case, a lowered threshold may lead to disastrously maladaptive consequences (e.g., Othello), the fit between the cue and the direction of calibration indicates adaptive patterning. Being jealous under these circumstances may be “realistic,” in the sense of having led to adaptive outcomes on average in ancestral environments.8

Most clinicians—especially cognitive behavioral therapists—would likely read this fictional client’s response as maladaptive, when in fact it’s the very definition of adaptive. Why is it adaptive? In part because it mostly ignores the client’s personal history and whatever half-baked notions the culture of clinical psychology happens to hold at the moment, in favor of the overwhelming evidential weight contained in the client’s intuition.

I’m not saying the average therapist would dismiss the possibility that sexual jealousy is an evolved adaptation, with countless data points embedded in its design; I’m saying they wouldn’t even be aware of it. In all three years of my postgraduate training, evolution wasn’t mentioned once.

Just to make sure my experience isn’t unique, I’ve added a quick poll for any mental health professionals reading:

Unfortunately, even those exposed to evolutionary ideas often dismiss them. According to Berg-Cross (2001), “Many mental health experts do not buy the evolutionary argument and have concluded that all jealousy is maladaptive” (p. 36). It may be that in arguing for a shared human nature—one that responds more to situation than to personality or personal history—evolutionary psychology runs counter to the “person-first” ethos of the field.

In any case, the result is that instead of asking helpful questions such as—Why did sexual jealousy evolve? What cues does it attend to? Does it operate differently in men and women? How might the modern world be confusing it?—the average therapist rolls up their sleeves and starts asking what unique thing about this client is driving their experience. The problem of sexual jealousy shifts from a dynamic between partners to a quirk (or perhaps defect) of the individual. A psychology that forgets—or rather, never knew—species history will frequently mistake design for dysfunction.

So let’s step back and regard the modern person with some empathy. They’re tasked with navigating a truly ridiculous amount of conflicting information. First, they have multitudes within them: the best science shows that each of us is less a single organism than a coalition of semi-independent systems. (The digestive system may seek relief even as the reproductive system shouts, “Not now!”) Second, the once-tight fit between cue and response has been disrupted by a modern world very different from the ancestral one in which that relationship evolved. Third, culture has always been a confound—and the culture of clinical psychology, in particular, has lost the forest of human nature for the trees of the individuals it treats.

Let’s pause for a moment more on the hubris of my field. My colleagues and I sit down with clients who have—just like us—millions of years of trial and error guiding their perceptions and motivations. What do we do with this treasure trove of information, this most well-powered study? Not only do we ignore it, but in many cases, we work against it. With our fancy ideas, we drive a splinter between the client’s head and stomach. A therapist might conclude that a client is acting “illogically” based on…what? A few years of schooling spent reading people who were, much as I love many of them, mostly talking out of their ass? Definitions of rationality and human nature only a few centuries old? The current clinical cultural milieu, which endorses ideas that flatter our values more than explain our nature?

On the basis of these shaky foundations, the therapist feels justified in poking holes in what often turns out to be a client’s evolved wisdom. We call it “insight” when someone doubts their instincts, and “progress” when they learn to override them. But much of the time, when clients sense something amiss, they aren’t wrong. They’re simply caught between the wisdom of their species, the distortions of modern life, and the cultural beliefs of clinical psychology. The result is confusion—people taught to mistrust the very machinery that brought humanity into the here and now.

In the final post, we’ll discuss the final variable in the equation—behavior—before turning to the implications of accepting that the situation matters more than the person in it.

References

Berg-Cross, L. (2001). Couples therapy (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (1999). Toward an evolutionary taxonomy of treatable conditions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(3), 453-464. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.108.3.453

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1990). On the universality of human nature and the uniqueness of the individual: The role of genetics and adaptation. Journal of Personality, 58(1), 17–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00907.x

It’s a bit more complicated, of course, because over time, a person increasingly chooses the environments which shape them. Pinker writes, for example, that “the heritability of intelligence increases, and the effects of shared environment decrease, over a person’s lifetime. One explanation is that genes have effects late in life, but another is that people with a given genotype place themselves in environments that indulge their inborn tastes and talents. The “environment” increasingly depends on the genes, rather than being an exogenous cause of behavior.”

p. 188, italics original.

Again, this is why I prefer “situation” to “environment.” It feels odd to say that someone who must act quickly inhabits a different environment than someone who can take their time, but they clearly face a different situation.

That said, a full list should absolutely be compiled for this and every emotion. In fact, on the first day of their training, therapists should be handed this “Sparknotes” guide for the top ten emotions they’ll encounter in their work, from sexual jealousy and anger to anxiety and depression. This alone would be worth more than the sum of what I was taught in my graduate program at LaSalle—and the crazy thing is, most of this information already exists!

Some recent work has challenged the view that evolution proceeds too slowly to shape modern minds, so perhaps our brains are more up-to-date than previously thought.

For example, in this paper examining the topic, the authors write: “ACEs [Adverse Childhood Experiences] were positively associated with anxious and avoidant attachment styles, but only avoidant attachment was significantly and positively associated with cheating frequency.” You’ll have to wait until Part III for my thoughts on attachment styles.

Shout out to Don Brown and his book Human Universals for breaking the ice on the idea that beneath all human variation lies a shared human nature.

p. 53

I find I have been working from a very similar place and have also used a cake metaphor. This weekend I think I will work on a piece comparing our approaches by way of cake.

I've been using the word 'worlding to cover this worlding of the self among others doing the same (as a fractally done dance of necker cubes) [a situationing of the person situated among other persons situating the same].

Will have to come back for a closer reading.

beside the substack blog the original cake reference is at:https://www.academia.edu/40978261/Why_we_should_an_introduction_by_memoir_into_the_implications_of_the_Egalitarian_Revolution_of_the_Paleolithic_or_Anyone_for_cake

Notes:

① “awe organ” more likely a reward centre for worlding well (we have no organ for truth either, this is why they can be conflated "feeling awe I saw the truth".

② to mix our cake batter/metaphors : we have an urge to world in the current situation, as person selfing a shared recipe in their own way, because we/they are hungry, but have to wait on somebody to get back home with the icing, and when it comes together we feel comfort in the routine (more selfie), or awe in the perfection (more wordly). So if it fails to come together, no icing to be found, we unwisely blame the messenger.

The outcome of all this affect all levels of the cake, some in proximate terms (at hand) and some as traces or echos which we will have to find out about using taphonomy rather than geneaogy.

③ many 'differences' are the outcomes of the worlding urge which is unrecognized by psychology and sociology/anthropology (I have a social ecology background). I.e we wonder why we back cakes differently but not why we bake cakes.

Cakes:recipes :: the social animals activities : a black forest cakes arises in a situation of histories and proximate choices.

social animals activities : religion/art/performance/polity/markets (cakes) and their instances black forest cakes

④ there is no gene for religion, just as there is no gene for Unitarianism, just as there is no gene for a language

⑤ we have an "urge" to world the self among others (firstly family until we individuate the self from the world we live in (or fail to separate as narcissists), then we forget the world (situation) and via attribution theory see all things in the person (in WEIRD societies) or forget the self and world without end (also a type of narcissism). Most societies can be placed within that range of proportions, which is here people find themselves (pun intended).

⑥ it's a mess because evolution don't care as long as we have a go, doing nothing will often get you killed, but in a social learning species some sort of comparative advantage kicks in and it's better to be dumb and a bit wrong, than to be too careful and motionless (fight/flight:freeze) Bad news, anxiety is never going away.

But we will continue to feel it _should_ go away. It should be better... something should be done.

⑦ on our social ecology course we had a lot of counsellors, psychologists etc, we joked we would socialise the life out of them.... party party party

⑧ I'll wait for part three for a post which these notes will work towards