Technology, Part IV: Artificial Solutions to Artificial Problems

If we have to live in a zoo, let's make it a nice one.

So far in this series, I have tried to make three basic points:

Throughout the course of human history, technology has improved many important outcomes, but it might not have bettered our experience. For example, the technological progress over the last century in the U.S. has neither increased life satisfaction nor granted more leisure.

In the meantime, many of technology’s negative byproducts—such as climate change—have been slowly accumulating in the background. Another slow-accumulating effect is evolutionary mismatch: the growing divide between the environments in which we evolved and the environments in which we live.

In my opinion, evolutionary mismatch is the largest unacknowledged cause of mental illness and unhappiness. If we want to improve mental health, we need to take mismatch seriously.

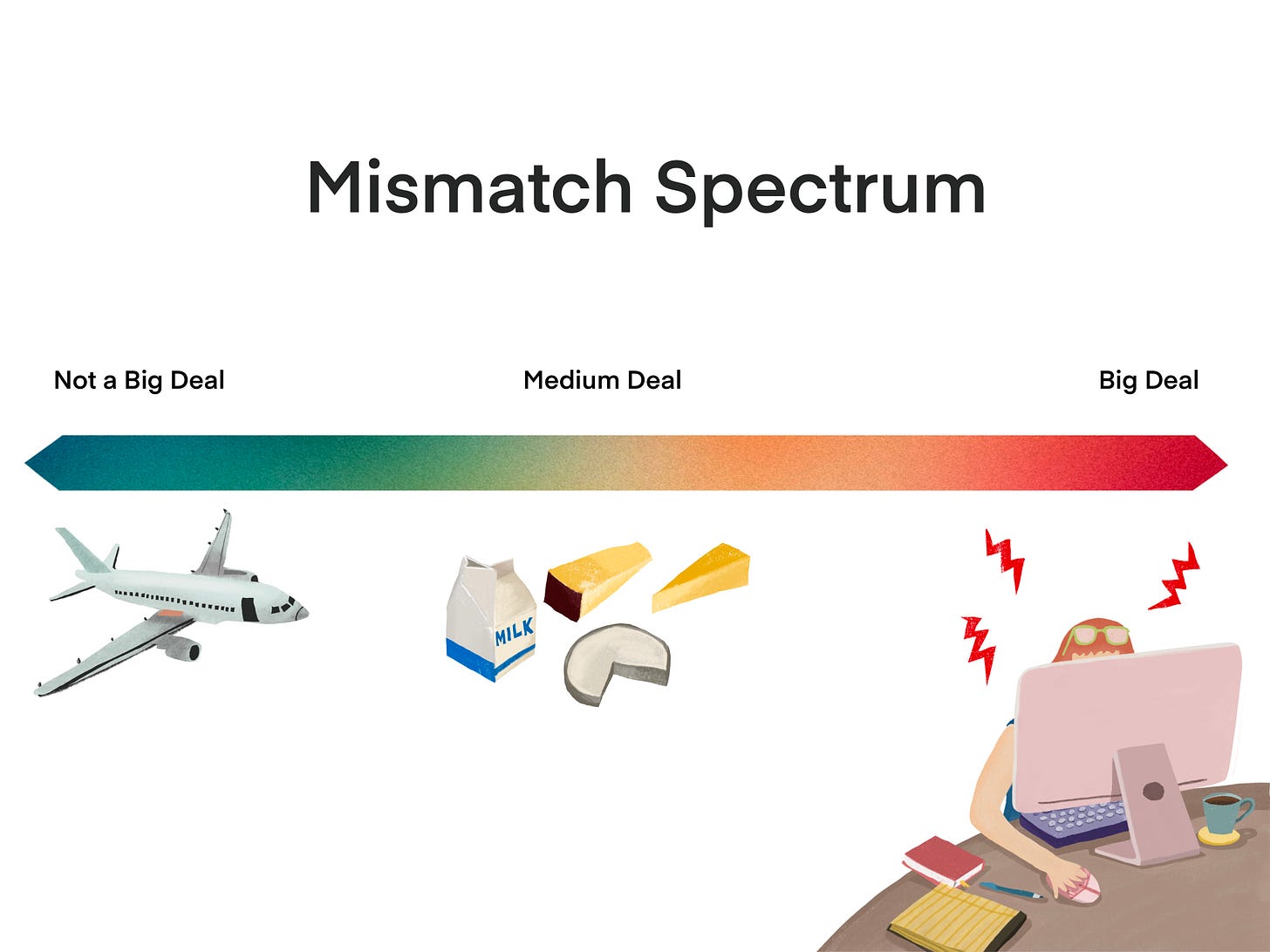

Even for those whose mental health is fine, evolutionary mismatch is a quietly powerful perspective. Humans evolved in a world almost inconceivably different from the one today. Environments of evolutionary adaptedness (EEAs) contained far fewer people, much less scientific knowledge, and almost nothing artificial. That is, there were no airplanes or cell phones, no cement or condoms, no eyeglasses or braces, no TV or skyscrapers. Of course, as some of these examples suggest, much mismatch is insignificant, analogous to the impact of a few dust particles on our lungs. We should therefore think of mismatch as occurring on a spectrum from not a big deal (air travel) to big deal (chronic stress), with plenty in-between:

Although much mismatch doesn’t have a noticeable effect on our well-being and can be ignored for the purposes of creating happier people and societies, the ubiquity of mismatch is astounding. It’s everywhere we look, though rarely what we see. To that point, what’s perhaps even more astounding is that humans haven’t assumed a wholesale alteration of their environment would have myriad downstream effects, both physical and mental. I mean, even now, mismatch is a fringe idea that most people have never heard of. It wasn’t in the same zip code as the stuff I was taught in my graduate program. So what gives?

Part of what makes mismatch difficult to spot is that it’s often a matter of degree, not kind. For example:

Our ancestors interacted with other people, some of whom were strangers; they just didn’t interact with thousands of people, most of whom are strangers.

What would we expect, given this difference? Higher resting anxiety. A stranger, after all, is someone whose behavior we are less able to predict.

In the past, people encountered loud noises and hot temperatures; just not noises this loud or temperatures quite this high (especially this year on the East Coast, sweet heavens…)

What would we expect, given this difference? Higher average anxiety and irritability.

Prehistoric peoples made mistakes and were ashamed; but their mistakes were never broadcast so widely or preserved so perfectly.

What would we expect, given this difference? More fear of making mistakes and a longer tail of guilt afterwards.

Foragers were undoubtedly interrupted in the middle of a task, but presumably much less often than eight times an hour.

What would we expect, given this difference? Shorter attention spans, more fragmented thought, and higher resting anxiety.

Humans have always felt envious of others, whether for their status, beauty, partner, hut location, or whatever, but until recently, they never compared themselves to someone who had so much more than them.

What would we expect, given this difference? More anger, envy, and crime.

Of course, in addition to differences in degree, the modern world contains differences in kind: airplanes, psychiatric medication, reading. These forms of mismatch are much easier to notice, but probably represent a smaller share of the problem. It’s mostly stuff that has been ratcheted up in intensity that we need to address.

Artificial Solutions to Artificial Problems

The modern world can be confusing and overwhelming. One way to cut through the noise is to recognize the prevalence of artificial solutions to artificial problems.1 This describes most of the stuff—materials, processes, ideas—that you and I encounter daily.

Washing machines, which I discussed at excruciating length in Part I, are a solution to the problem of washing clothes by hand; clothes are a solution to living in colder climates than we evolved in. Eyeglasses are a fabricated solution to the problem of looking close, whether at a screen or book.2 Dentists spend most of their time counter-acting the modern diet. Sunscreen caters to the evolutionarily-recent desire to sit for hours upon end in direct sunlight. Government was invented to organize more people than should probably be organized. The idea that “everything happens for a reason” is a salve for the many scientific discoveries indicating that it doesn’t.3

Even the title image, which I chose for its beautiful absurdity, shows an artificial solution to an artificial problem. Some people long for the ability to see the night sky as they fall asleep, but because roofs were invented to keep us and our stuff dry, we now need night-sky projectors:

Most of what Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) society members encounter in their day-to-day are human-made solutions to human-made problems. Obviously, humans haven’t tried to make problems for themselves. It’s just that there are tradeoffs to everything. When a technology is invented to solve Problem A, it generates externalities B, C, and D. Whether positive or negative, these externalities are typically subtle, unanticipated, unregulated, and/or not the inventor’s responsibility. I’m guessing that whoever came up with roofs didn’t foresee (or care) that people would miss the stars. As Heying and Weinstein (2022) put it, “The benefits [of a technology] are obvious, but the hazards aren’t.”4

Not all externalities are problems, but when they are, guess what the solution is? That’s right, more technology.

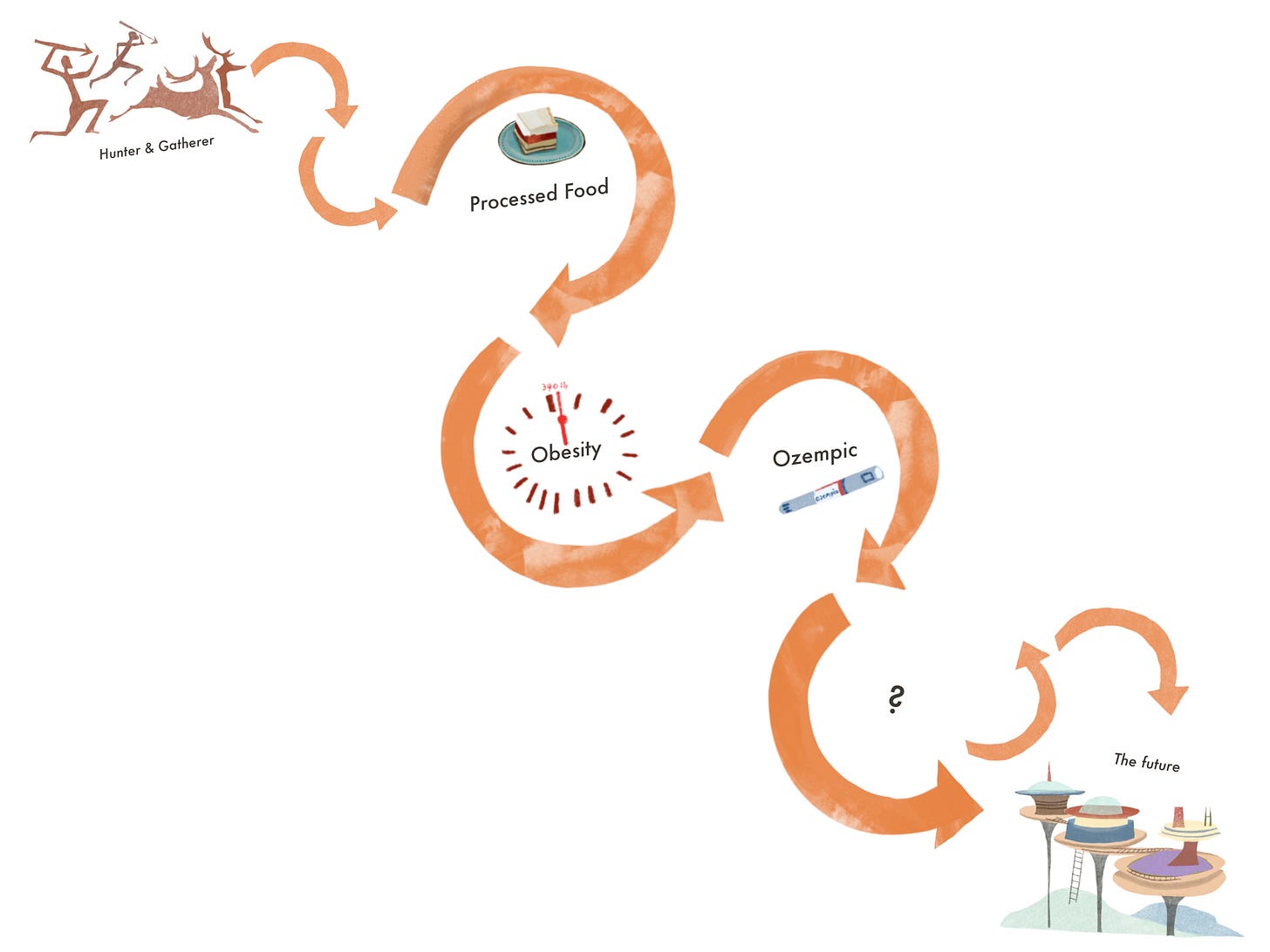

Take Ozempic as an example, which sits in the middle of a long chain of problems and solutions. As a drug that helps people lose weight by curbing appetite, Ozempic is a solution to obesity, which is an artificial problem created by advances in agricultural and food-processing technologies, which were previously a solution to hunger, an OG problem. Likewise, although Ozempic is now seen as a solution, it will undoubtedly one day become a problem. Whatever the nature of this problem, you can be sure that additional technologies will solve it, whether a different drug with fewer side effects, or new drugs that counter-act them:

Why is it important to note that the problem of obesity is artificial, or human-made? Because while evolution has a suite of defenses against longstanding problems, it’s relatively useless for the “hyper-novel” problems of modernity. This is one of the major, underdiscussed drawbacks of humanity’s progress: that we’ve essentially flushed millions of years of evolutionary fine-tuning down the toilet.

For example, the human body contains myriad adaptive responses to starvation, from decreasing fertility in times of nutritional scarcity to switching to fat as the main energy source (away from carbs) after 24-48 hours without food. Guess what the body doesn’t have many defenses for? Obesity. In fact, the body actively works against people who are trying to lose weight, even if they are severely overweight.

So it’s not just that we’ve dropped evolution as an ally; in some cases, we’ve made it into a nemesis.

How about therapy?

If natural selection equipped us with defenses against problems we frequently encountered throughout our history, then presumably we have some readymade defenses against mental illness and insanity. As Adam Mastroianni notes, a chronically depressed or manic person doesn’t do that well in life. Neither does someone who routinely hallucinates, pulls their hair out, or chooses not to eat.

Psychology has highlighted some of these fundamental defenses—sleep, social connection, and so on—but there are likely more that haven’t been uncovered. Homo sapiens’ main defense, of course, might be the same as that for every organism: living in an environment that is syntonic with its design.

As the world becomes more artificial, we might not be able to rely on our primevel defenses. (In some cases, as we saw with weight loss, these defenses might work against us.) Increasingly, humans will have to invent what is good for their mental health. The problem is, we don’t know what good mental health requires. While modern science understands nutrition and vision well enough to provide people with vitamins and glasses, respectively, it doesn’t understand the brain well enough to provide people with more than therapy and medication at this point—blunt tools corresponding to our blunt knowledge.5

At base, I see therapy as one of many artificial solutions to the artificial problem of modern mental illness. I think of therapy as a post-industrial patch,6 a temporary fix to the more permanent problem of a world largely devoid of meaning and belonging. For example, many modern people do not have the luxury of believing that they or their tribe is special, that there are spiritual forces at work in the world, that they are part of something greater, or that some form of life continues after death.

Consider a moment I had with a client a few years ago. For many years, this client—let’s call him Dave—struggled to accept his father’s death. One session, over the phone, Dave was relating a dream he’d had the previous night in which his dad told him: “Son, you’re going down the wrong path.” Dave was mulling a career change at the time, you see. After telling me about the dream, Dave didn’t say anything for a few seconds. When he spoke, it was clear that some emotion had crept into his voice. “You can understand how people of the past would’ve thought this stuff meant something,” he said. “But of course, I know it’s just neurons firing.”

Contrast this with the harvest feast of northeastern Malagasy7 as related by Heying and Weinstein (2022):

During the annual ceremony, the bones of a select few ancestors are disinterred8 after the harvest. Those who have died recently, who were in body boxes, are rewrapped and put back in smaller bone boxes…While the dead are out and about, though, the living take the opportunity to speak to them, to tell them of the major events of the last year—the size of the harvest and the frequency of storms, births, and marriages…[eventually], an elder stood up and addressed the villagers—ancestors and living alike…His tone moved easily between sober respect and lighthearted memories, and his jokes were well received. He was clearly beloved. Sometime in the future, one of the living would be addressing him as one of the ancestors, in much the same way.9

The therapeutic creed says that Dave needs to “process” his father’s death, and then provides a tome of information about how this can be done, most of which is closer to mythology than science. For my money, as long as we’re telling stories, I like the Malagasy’s version better.

Anyway, if therapy is a devised solution to mismatch, then to the extent that mismatch goes away, so does the need for therapy. My client might not be coming to me if our culture had a meaningful ritual in the face of death. That ritual would be his therapy instead.

Climate Change for Our Brains

If the largest portion of unexplained unhappiness is due to evolutionary mismatch, which is largely a result of technology, how do we fix it? Part of the answer has to be “with more technology” because artificial problems often require artificial solutions.10 For example, it is much easier—not to mention more realistic—to design cities that are more aesthetically pleasing than to get rid of cities altogether.

But the other part of the answer is: with culture. People need to clamor for beautiful surroundings.11 Culture dictates, to a significant extent, how investment in technology is spent, just as new technologies influence cultural change. And nothing is written in stone that these two forces must exacerbate mismatch; with a slight change in perspective, they could begin to shrink it.

Consider the climate crisis. People from all walks of life—at least in WEIRD societies—are already factoring the environment into much of what they do. Hell, my wife and I have four different ways to throw things away, something that, I must confess, drives me up a plant wall. But this cultural shift won’t be enough unless accompanied by major technological breakthroughs. Why? Because so many of our everyday technologies are fundamentally unsustainable. Even if Americans could be convinced, culturally, to drive less, they’d still be polluting the environment whenever they did. That’s why we need electric cars, too.

Could the same be said for the health of our minds, that we need both a cultural and technological shift? What if people were as convinced by the evolutionary mismatch argument as they are by the climate data? What if companies, innovators, regular citizens, and even governments began with the assumption that if something is going to resonate with the human brain, and allow for mental health, it ought to conform to the conditions in which that brain evolved? That would be a major first step in the right direction.

However, it wouldn’t be enough, because so many of our everyday technologies exacerbate mismatch. Just as technology needs to be redesigned with the ethic of sustainability if we are to reverse climate change, technology needs to be redesigned around the ethic of evolutionary alignment if we are to reverse mismatch. What would that look like? Here are some initial thoughts:

Insulate comparison: When people are given an opportunity to compare, they do. There are plenty ways we could cut down on this. For example, social media companies could hide how many likes a video gets, as Snapchat has done. This would allow both creators and viewers to focus on the content of the post, not the attention it receives.

Create naturalesque settings: “Our horizons are never quite at our elbows,” Thoreau wrote in 1854, but in the modern world, they very much are. How many people live in cities where they cannot see more than a few feet in front of them, walk in anything but 90-degree angles, enjoy anything green or aesthetically pleasing, let their children run around, go for a walk on something that is not cement, and so on? Examples of how we could fix this are myriad and obvious—e.g., less development, more green space—although not necessarily easy.

Protect mental engagement, or “flow”: There are already studies showing that productivity increases when email is removed. Related studies highlight the staggering amount of interruption in the modern workplace. Many clients trudge into my office after their workday, worn out not so much from focus as distraction. Imagine if we protected people’s ability to think deeply in the same way as we protect their ability to use the bathroom alone?

Constrain choice: To be fair, it’s pretty tough to get this right. In some instances, choice restriction is awful. In others, it’s lovely. The good news is that merely the recognition that more choice isn’t always good would be a huge step in the right direction. Right now, the idea that more choice = better is largely unquestioned.

Guided by a Living Fossil (not me!)

In the first post of this series, I recounted my serpentine path to evolutionary psychology. I wanted to understand, at the deepest possible level, the clients I was supposed to be helping. Evolutionary psychology offered the most helpful framework. By focusing on what humans share, it helped me understand many previously confusing experiences—for example, why I was able to predict how my clients would feel about something before they told me, or why circumstance often seemed to be the only difference between us (a major part of which, by the way, was my role as therapist and theirs as client).

As I continued to mull the role of context, I became convinced that evolutionary mismatch is the most important, and least discussed, factor in modern human experience—both for good and bad. The next step was to investigate the role of technology, because technology is what rapidly transforms our world from one that we are prepared to experience to one that is strange—even if it is in some ways better. After that, I wanted to provide specific examples of how modern people suffer from mismatch, using my caseload as inspiration. I tried to stress how subtle, even inexpressible, many of these miseries are—like those of a fish out of water.

Wouldn’t the first step toward a solution, then, be to build awareness and language around the problem? That is what I’ve tried to do in this series.

Big picture, how can we make life better going forward? If we want to sustain population-level mental health, we must do more than take away smartphones or provide better schooling, although both represent a step in the right direction. More broadly, what we really need is to redesign the zoo we’re living in to more closely resemble our native habitat. In doing so, we must be motivated by evolutionary match in the same way our climate efforts are motivated by sustainability.

My hope is that Living Fossils is helping to clarify what is needed for sound mental health, but it will likely be a long, long time before humans possess the equivalent of nutritional daily values for what makes them psychically well. But at least evolutionary psychology has framed the house. In the meantime, there is plenty of information available on the kinds of environments in which our brains underwent their long and glorious development, which at the very least offers a blueprint for how things could begin to look again. And each of us has input from the brain itself, a living fossil that emits a signal despite all this modern noise. Triangulating with these three, we should have everything we need to strike a better path.

References

Heying, H., & Weinstein, B. (2022). A Hunter-gatherer's Guide to the 21st Century: Evolution and the Challenges of Modern Life. Swift Press.

I’d like to give Johann Hari credit for this phrase because I swear I heard it in this podcast, but I can’t find it in the transcript, and there’s no way I’m listening to it again just for a cite.

I once went on safari in Africa, and even though our guide was my age, he could see about twice as far.

In other words, things happen due to cause and effect, not because someone in the clouds has a plan. A dedication to scientific principles demands this acknowledgement, but it’s understandable why people would prefer not to acknowledge it.

p. 98.

Even as a therapist—maybe especially as a therapist—I am willing to admit that therapy is a blunt tool if there ever was one. But hey, at least it’s sharper than medication!

Katiyar et al. (2023) convinced me that the Industrial Revolution initiated one of the most—if not the most—abrupt shifts in lifestyle over the course of human history, which created all sorts of mismatches that our technology ever since has been trying to patch. For example, the Industrial Revolution forced millions of people from the countryside into cities, resulting in dramatic upticks in many physical and mental illnesses. (Schizophrenia is still linked to city-dwelling.) Since then, medical technologies have helped patch the first, and many other technologies have helped patch the second. Therapy should be seen as one such technology; perhaps it’s no coincidence that it was founded by Freud in 1890.

people from Madagascar; I had to look this up

Why do academics always use words you have to look up? This one means “dug up.”

p. 86-87

Not always, of course. Sometimes, simply doing what a hunter-gatherer would do solves the problem.

Anyone who has been to Providence, RI in recent years knows what kind of difference a commitment to aesthetics and design can make.

Soooooo good!

I thought this was a terrific post. I haven't really given much thought to evolutionary mismatch until now but I think I will from now on. The constant nagging feeling that something isn't quite right might just be an awareness that the modern world doesn't feel like home.

I teach Conversation English to foreigners and have to think up topics for discussion. One is, 'If you had a time machine, would you rather travel into the past or the future?' While my students are discussing it, I always think that I personally would always travel into the past. I suspect this is because the further back you go, the less the mismatch.

Of course, I'm enough of a modern (weak, pampered etc.) to actually want a certain amount of technology: give me modern anaesthetics any day over a handkerchief and stick thrust between the teeth! Yet it would be nice to reduce these 'cheats' to a minimum.