The Solution Problem (Part 1/3)

The beginning of a longwinded answer to why mental illness appears to be increasing.

“…had you read more upon the subject, or less, you might have been cured long ago.” – The Haunted Man by John Neale

In my opinion, one of the deeper questions a person can ask these days is: “Why is there an increase in mental health diagnoses in the U.S.?”1 A comprehensive answer would explain the rise in gender dysphoria, eating disorders, and ADHD alike.

Now, you might think a mental health professional would be most qualified to answer this question, but personally, I would trust them the least. They are too close to the situation to recognize that this isn’t a question about mental health. Ultimately, it is a question about evolution and technology.

I realize this is confusing because here I am, a licensed professional counselor, attempting to answer the question. But hopefully I have established myself as a renegade by now, as someone trying to change the mental health industry from within. People tend to critique, after all, what they still believe in.

But let me be clear—the mental health scene is a mess. The first edition of The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) was published in 1952 and contained 106 disorders. Every edition since has expanded its purview. Now, nearly half of Americans will qualify for a mental health diagnosis at some point in their lives. People are flocking to therapy in droves, and the use of psychiatric medication continues to rise for both adults and children, despite underwhelming evidence for its effectiveness.

What gives? I mean, these developments have occurred during arguably one of the best times, and in the best places, to ever be alive.

One answer is that these trends are part of progress. “Just as people used to die by the millions from tuberculosis,” this answer goes, “so people used to suffer silently from undiagnosed mental illness. Thankfully, due to better science, increased awareness, and decreased stigma, this is no longer the case.”

The progress answer has some merit to it, but not as much as people commonly believe. This is because, while the underlying mechanisms of tuberculosis have been discovered, the underlying mechanisms of most mental illnesses have not. Even when a mental health treatment works, then, nobody really knows why, reducing the scientific enterprise to a game of Battleship.2

Take schizophrenia. Antipsychotics can drastically reduce some symptoms (e.g., delusions and hallucinations), but cannot improve others (e.g., flat affect), nor do they reverse the course of the illness. Behavioral interventions cannot cure schizophrenia, either, despite over a century of research and experimentation.3 In fact, the best weapons of the clinical community cannot cure most serious mental illnesses, which afflict about 6% of the adult American population.4

In many cases, we aren’t even sure that we’ve defined or isolated the illness correctly. As Anne Harrington writes in Mind Fixers:

In 2008 a group of researchers launched a multipart project designed to identity and critically assess all ‘facts’ currently established for schizophrenia...As these researchers reflected in 2011, the field seemed to be operating ‘like the fabled six blind Indian men groping different parts of an elephant coming up with different conclusions.’ In fact, they admitted, in the current state of knowledge, one could not rule out another possibility: ‘there may be no elephant, more than one elephant, or many different animals in the room.’5

This is a far cry from what can be found on Wikipedia’s page for tuberculosis: “Tuberculosis (TB)…is a contagious disease usually caused by…bacteria. Treatment requires…antibiotics.”

So, the progress answer doesn’t hold up for the most extreme cases of mental illness, and later I will show why it is an even poorer answer for less severe cases—for the other 44% of Americans who will be classified as “mentally ill” at some point in their lives.

Another explanation for the rise in mental illness is evolutionary mismatch. (If you don’t know what this means by now, you’re definitely going to fail the final.) The evolutionary mismatch hypothesis is that the difference between ancestral and modern environments has created or exacerbated some forms of mental illness, just as it has quieted or resolved others. As I argued in Is ADHD Real?, a spectrum of distractibility surely existed among our ancestors—as did every behavioral trait—but perhaps ancestral environments contained so little distractible material that those with lower thresholds didn’t face much of a problem. Or perhaps there were more productive outlets for hyperactivity. I could be wrong, but I don’t think they asked young boys to sit still and learn math in the Pleistocene…

Of course, modernity has quieted or resolved other forms of mental illness (e.g., syphilis-induced insanity) because it has found a cure to the underlying condition (i.e., syphilis). For these cases, the progress answer is clearly the right one.

In this series, I’d like to introduce a third answer—the solution problem—as an explanation for the rise in mental health diagnoses. The solution problem, briefly stated, is that solutions create problems in addition to solving them. According to this view, our society has so many mental health problems because we have solutions for them.

Snot a Problem Before

Let’s begin our journey with my new favorite product: the SnotSucker.6

Before this wonder of the modern world, snot was something parents and children just had to tolerate. It was a “problem” in the sense that it was unpleasant, but not in the sense that one could do something about it.

Or, rather, it was a problem whose solution was not worth the effort. Most parents “decided,” if you will, to tolerate it, rather than get in there multiple times a day with a tissue wrapped around their finger. If parents complained, it was in the spirit of—well, what can you do? Death and taxes are similarly unavoidable.

But the SnotSucker changed the equation. It made removing snot from a baby’s nose viable. For only $15 and minor respiratory effort, your kid’s nose can now be booger-free.

So, problem solved, right? Everybody wins?

Well, not exactly. Before declaring victory for any solution, three more questions must be asked:

What kind of problem does it solve? For example, if the problem was tolerable, was a solution necessary?

How much does the solution improve experience? If a solution fails to improve someone’s life, can it be considered worthwhile?

What are the solution’s costs? These must be weighed against any and all benefits.

What’s the Problem Here?

In Vacation Insights, I argued that the mind is constantly scanning the environment for problems and opportunities.7 That is its job—not to be happy, or maintain perspective, or overflow with gratitude.

The mind’s first question—is there a problem?— is followed by a second—can I do something about it? If the answer to either question is No, the mind moves on. If the answer to both is Yes, it rolls up its sleeves and gets to work:

This simple decision-tree provides a framework for the three types of problems below:

Unknown Problems. For example, high cholesterol. Many people don’t know they have high cholesterol, but it’s going do its thing regardless, so it’s still a problem.

Tolerable Problems. For example, the snot in your baby’s nose or the difficulty of opening something wrapped in plastic. People are aware of these problems, but in the absence of viable solutions, manage to tolerate them well enough. “It’s just one of those things, I guess. What can you do?”

Regular Problems. This is typically what we mean when we use the word “problem”—something a person is conscious of and can do something about. Once a person becomes aware of high cholesterol, they can change their diet and/or take medication.

The mind passes over the first two kinds of problems because, in the first case, the problem remains below awareness, and in the second, nothing can be done. Regular problems, though, are apparent and can be addressed. We’ll see in a moment why can so often becomes should.

By the way, what’s the point of dividing problems into types? To judge solutions, of course.

As an example, I have been experiencing some foot pain lately. As I continue to shuffle from one specialist to the next, I’ve noticed that the treatment plan depends on how much pain I report. When my pain is intense, more aggressive measures are taken, such as giving me two steroid injections within a month. But when the pain is manageable, the recommendation becomes “wait and see.” Unfortunately, this system can be gamed just like any other, so I am now in the pathetic position of having to exaggerate my pain just to be taken seriously. But that’s beside the point. The point is that we should be much less willing to run risks and tolerate costs when the problem is not acute in the first place. A solution should match the kind and severity of the problem.

Are People Made Happier?

The first question in judging a solution is: what kind of problem does it solve? The second question is: does it improve experience? Do people feel better because of it? If not, then some of the wind should be taken out of the solution’s sails.

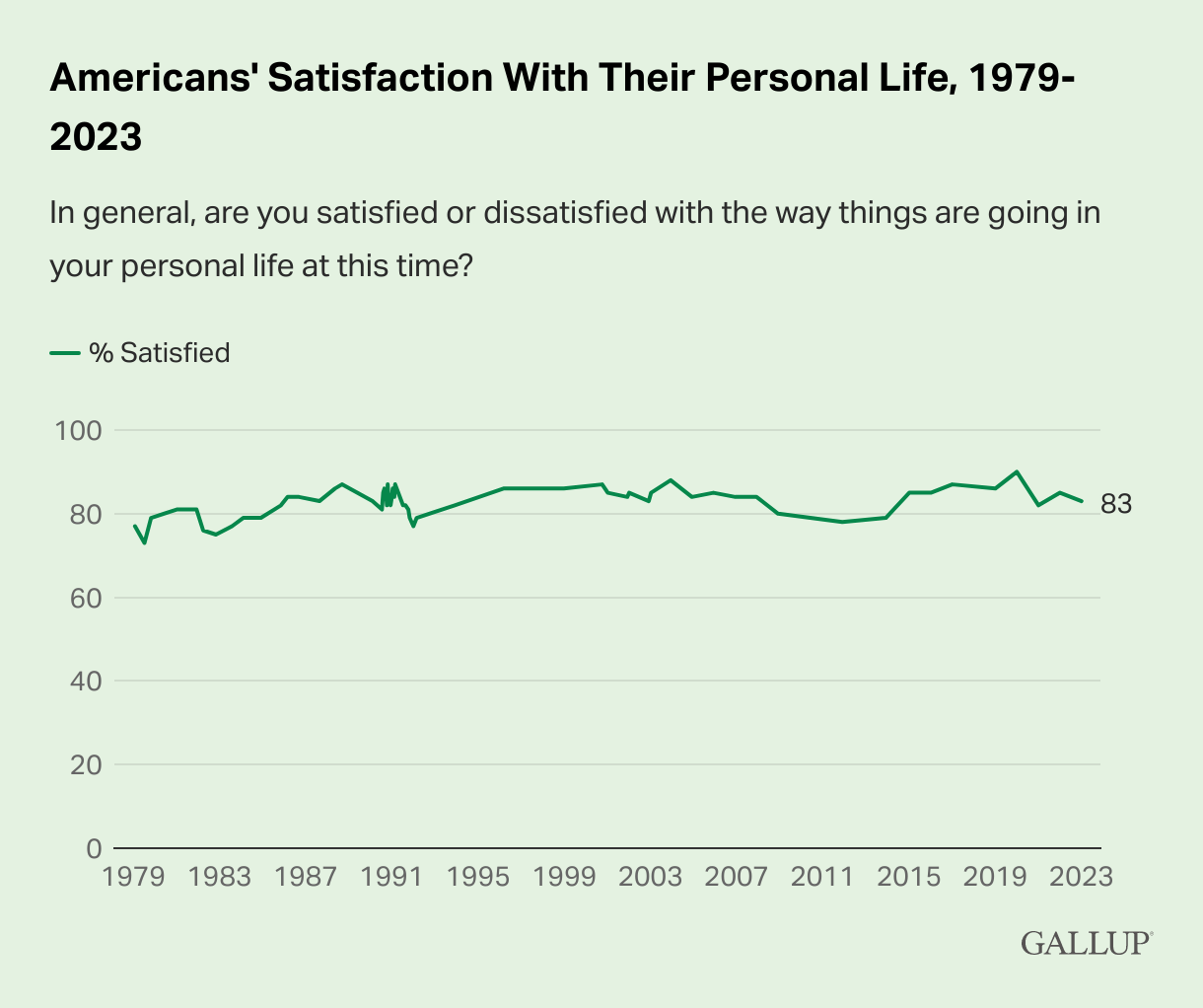

Odd as it may sound, solutions do not seem to improve experience all that much. (They certainly improve outcomes, though.) A fix for Problem A rarely makes us happier in the long run because we’ll soon be consumed by Problems B and C. This is essentially the story of the last 50 years of technological progress, during which time truly miraculous innovations such as the microwave, color TV, and air conditioning have made virtually no impact on Americans’ level of satisfaction:

As Adam Mastroianni writes: “We went from pooping in outhouses to pooping in climate-controlled bathrooms while machines do our laundry and cook our food, and our response was a collective ‘whatever!’”

Why is it that, as Oliver Burkeman notes in 4,000 Weeks, “The state of having no problems is…never going to arrive”?8 Ultimately, because the mind operates at the frontier of improvement.

Remember, evolutionary success is relative. If I have five children and you have four, I win. But if you have two children and I have one, you win. Of course, a person must be alive and in good enough shape to have and care for children—this is the absolute bar we must clear. That’s the floor, we could say, but there is no ceiling. Thus, a brain content with “good enough” will be easily outcompeted by one that focuses on the next possible improvement or advantage. Can often becomes should for the simple reason that should outcompetes can.

No matter how comfortable someone’s life, then, prolonged contentment is elusive because evolution cares about “better.” This explains why people don’t sail into the sunset after acquiring a certain amount of prestige, wealth, leisure, mates, or ceramic vases. Nobody says, “Now that I have 8 ceramic vases, I can die happy.” This kind of relative assessment is not unique to satisfaction and contentment, either. For instance, activities are not boring in and of themselves; they are boring compared to alternatives. Relief is not produced at certain points on the pain threshold; it is produced by experiencing less pain than before.

So much of human perception is rooted in comparison, and our assessment of problems is no exception. In fact, this dynamic might be particularly pronounced in the modern first world in which so many absolute problems—from starvation and violence to disease and weather—have been overcome. The result is that people like you and me might be dealing with more relative problems, whose basis is comparison. How badly I need to pee does not depend on the fullness of my neighbor’s bladder, but how satisfied I am with my number of vases does depend on the fullness of my neighbor’s cupboard.9

Summary of Part I

So, the SnotSucker comes around and solves a problem that people did not expect a solution for. That should take some of the shine off. Furthermore, owners of the SnotSucker won’t be any happier because another problem will soon present itself and demand to be taken just as seriously—even if it is not as serious. The misery plant tends to fill whatever pot it’s planted in.

All of this should make us less tolerant of a solution’s (frequently hidden) costs, to which we’ll turn in the next article.

As a final word, it should be clear that I don’t have a vendetta against the SnotSucker. (I haven’t even taken it out of the box!) I am simply using it to build a framework for how our society can judge solutions. The solutions I have in mind, of course, are those of the mental health industry, but it’s not only therapy, medication, diagnosis, and so on that I want to interrogate. I want to investigate what solutions do to the experience of misery more generally.

Indeed, I suspect that many things only become a problem after a solution is available. Isn’t sorrow made a little deeper by the ubiquity of antidepressants, which make suffering seem kind of stupid and pointless? Similarly, in a world with so much depression awareness and so many ways of treating it, who doesn’t occasionally wonder if their sadness is something more? A thousand and one professionals are prepared to confirm that it is.

Charlotte Joko Beck says: “What makes [something] unbearable is your mistaken belief that it can be cured.” I would propose something similar: “Sometimes, what makes something into a problem is the promise of a solution.”

Thanks for reading and stay tuned.

References

Burkeman, O. (2021). Four thousand weeks: Time management for mortals. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Harrington, A. (2019). Mind fixers: Psychiatry's troubled search for the biology of mental illness. W. W. Norton & Company.

Reports of mental illness are on the rise globally, too, but I’ll focus on America here.

I’m partial to this analogy because it captures both ways of generating hypotheses in the mental health space: random guesswork and guesses close to previous hits. The history of psychiatric medicine illustrates this wonderfully. The first class of antidepressants, developed around the 1950s, were discovered through sheer luck. Since then, pharmaceutical companies haven’t developed anything truly novel. It’s been safer—and more profitable—to make minor variations of existing treatments, and to keep poking around the neurotransmitter model of mental illness even though that ship’s been sunk.

We’ve had a century and change of little to no change.

In addition to schizophrenia, serious mental illnesses include Bipolar I, treatment-resistant depression, and borderline personality disorder.

p. 182.

If I haven’t mentioned it already, I have a baby now, which is why the SnotSucker is on my mind (and in my house). Please lower your expectations for my writing going forward.

I’ll use problem going forward as a shorthand for both problems and opportunities because to evolution they are the same—at least in the sense that both have important consequences for fitness and therefore must be handled well. It is bad for your genes if a date goes poorly or you step on a snake. True, stepping on a snake involves a more immediate and urgent cost, but a bad date costs a potentially fruitful relationship. So, both problems and opportunities are things we must respond to adaptively.

p. 180.

What determines whether a problem is absolute or relative? It is a good question that I don’t have an answer for yet. If anyone has any ideas, please comment.

Comparisons really are everything. I often think about how much I have in life—many things I once dreamed of—yet I constantly feel stressed and anxious about small, everyday problems. Yesterday, I reminded myself that many people have far less than I do. Instead of making me feel grateful, it made me feel worse.

Then I thought: people who have much more than I do probably aren’t any less stressed in their huge mansions—if anything, they might be more stressed. What are they stressed about? I can imagine plenty of things. Strangely enough, that thought made me feel much better.

It is rare that I read something novel and insightful. What a lovely surprise this article was! I subscribed immediately. I look forward to both the next installment of this article and all of the back catalogue!