The Solution Problem (Part 3/3)

Why was my answer so long-winded?

By the end of this post, I will have written close to 9,000 words in response to the question: Why are mental health diagnoses on the rise? Hopefully, my answer has been so long-winded because it has had to be.

But let’s back up a second. Why are more answers needed? Don’t we have enough hypotheses, from progress and evolutionary mismatch to smart phones and social media?1 Isn’t some combination of these sufficient to explain the supposed increase of psychic suffering?

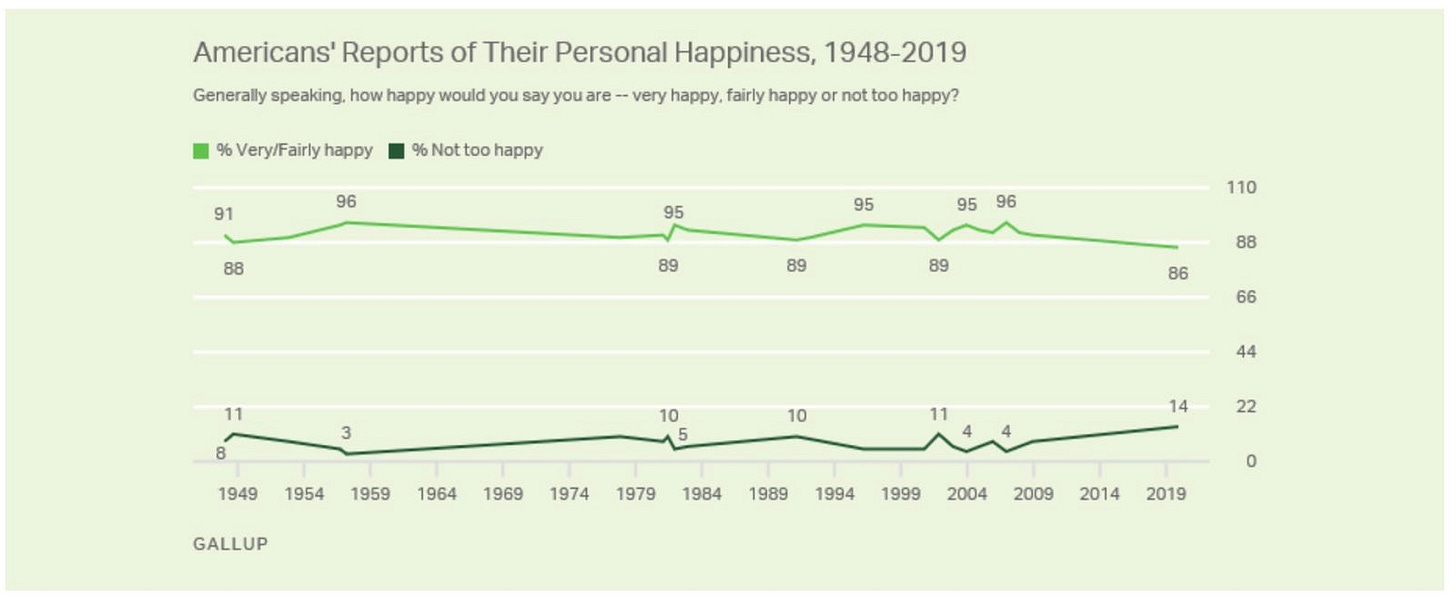

No. In my opinion, the sum of proposed answers leaves something missing. For example, the progress answer has no way of reconciling how people of the past, without SnotSuckers, heated steering wheels, or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), were nevertheless fine. By many measures, they graded their lives the same as we do:

For my money, the missing piece is the solution problem: the tendency of solutions to create problems in addition to solving them, making the dance of problem and solution more circular than linear. Only via the solution problem can we understand why solving problems doesn’t render us problem-free or improve our experience all that much.2

The solution problem is what happens when a mind that evolved for scarcity meets a world of technological abundance. Our ancestors would have swapped their problems for ours in a second, but the modern person has no way of sustainably appreciating that fact. Since evolutionary success is relative, the mind simply confronts the problems it perceives, and thus each person is mired in predicament. This is why I claimed in Part I that the reported increase of mental illness isn’t primarily about mental illness, and therefore shouldn’t be entrusted to mental health professionals to explain or fix. The solution problem applies to the nature of problems and solutions in general; mental illness is but one example.

By the way, why is it so tempting to assume that people of the past must have been miserable? By “people of the past,” I mean early 20th-century women who spent hours a day doing laundry, hunter-gatherers whose lives were long considered “solitary, nasty, brutish, and short,” and everyone in between. These people seem miserable because we look back on them from our current advantage. Manually scrubbing clothes seems harder when there is an easier alternative. Air-drying becomes slow as soon as a dryer does it faster. Yet one day, there will be an easier and faster alternative to our modern washer and dryer, allowing people of the future to pity us. Should they?

At any rate, I had to be long-winded about the solution problem because, as far as I can tell, not many are promoting it, especially when it comes to mental health. Not many are making the argument that mental health solutions are partly responsible for mental health problems. I thought that if I did not take my time and provide the reader with enough context to understand my argument, it would be dismissed—or worse, taken to mean that I am unsympathetic to others’ suffering.

The Progress Answer for Mental Health

Applied to mental health, the progress answer holds that countless unfortunate souls in the past suffered silently from conditions we now have the luxury of diagnosing and treating. It argues that the growth of diagnoses reflects our modern sensitivity and science—both positive developments. My guess is that most Americans would agree with this view, and I’m nearly certain the average mental health professional would agree wholeheartedly.3 According to this perspective, if we could only further increase awareness and reduce stigma, and perhaps station a therapist on every street corner, all would be well.

To be fair, the progress answer is valid for many aspects of modern life (e.g., medicine), including some mental health conditions. Take dyslexia: first identified in the late 19th century, dyslexia became increasingly well understood over the 20th, paving the way for more effective interventions. As a result, someone with dyslexia today has far more resources than they would have had 200 years ago—and is better off for it.4

But I don’t think the progress answer holds for the majority of the disorders included in the DSM, and here’s why: it’s not clear that these disorders actually exist or that there’s a benefit from being diagnosed with them.

Let’s say that based on family stories, you suspect that your great-grandfather had ADHD. (And let’s pretend for the moment that ADHD is real.) He almost certainly would not have been as conscious of his condition as he would today, given that there wasn’t even a shorthand for it. But would he have suspected that something was off? Would he have considered himself different—even less—than others?

The progress answer says: Yes, he suffered in the shadows of the ignorant society around him. But the solution problem says: Nope, he probably didn’t even notice.

Remember, the mind must first attend to something, and then classify it as a problem or opportunity, before it tries to solve it. Without much of a mental health infrastructure around him—most notably, without a bona fide diagnosis—your great-grandfather likely had no clue that anything was amiss.

But let’s say, for argument’s sake, that your great-grandfather came to recognize a higher distractibility in himself than others. That’s not entirely unlikely, given that I notice differences in myself for which we don’t have much societal or scientific awareness (e.g., tendency to daydream, affinity for routine). His mind would have then moved onto the next question: Can I do anything about it?

Now, the answer might have been Yes or No, depending on some other factors. If No, your great-grandfather would have gotten to tolerating his high distractibility (for instance, by ignoring it). If Yes, he would have attempted to solve or improve it. But here’s the key: his options would have been humbler than they are today. Fewer, simpler, less expensive, more personal. Indeed, for all you know, your great-grandfather chose his trade of lumberjacking based on a semi-conscious understanding that he couldn’t possibly sit still all day. But he certainly wouldn’t have been on medication, in therapy, or reading Your Brain’s Not Broken: Strategies for Navigating Your Emotions and Life with ADHD (A Playbook for Neurodivergent Men and Women with Tools for Coping with ADHD).

Think about it this way. There is a good chance that you, dear reader, suffer from some suboptimal way of being which future science will clarify as a disorder, burden, or handicap. But you don’t know it now. So, while you might achieve poorer outcomes because of it, you don’t know that you achieve poorer outcomes. Given the choice, would you want to know? Before you answer, keep in mind that your disorder might not be valid, cannot be confirmed, and probably has no complete or permanent resolution.

Oh, and that if you do happen to “solve” it, you won’t be any happier.

So, the progress answer points to glut of disorders in the DSM and says: The mental health industry has rescued people from all these ways of being. In contrast, the solution problem points to the DSM and says: For each of these ways of being, the mental health industry has created a problem that now requires a solution.

Which is correct? Given that half of the U.S. population will meet the criteria for a disorder at some point in their life, I’d say the answer matters.

Is Diagnosis Ultimately Helpful?

In Limits to Medicine, Ivan Illich writes of medical diagnosis:

Diagnosis always intensifies stress, defines incapacity, imposes inactivity, and focuses apprehension on nonrecovery, on uncertainty, and on one’s dependence upon future medical findings, all of which amounts to a loss of autonomy for self-definition. It also isolates a person in a special role, separates him from the normal and healthy, and requires submission to the authority of specialized personnel.5

I agree with much of that, but I think Illich misses two points. First, an accurate diagnosis obviously helps to steer treatment. Second, receiving a diagnosis can produce a tremendous amount of relief. A mental health diagnosis, in particular, is not only an explanation of suffering—it is an excuse for being. It’s a hall pass that people can wave around in defiance of pressures and expectations from others. It justifies not only who a person is, but what they have done, and in some cases backstops how they really want to act moving forward. Who wouldn’t want that?

But this fades, just as compliments and reassurances do, and eventually many of the problems that Illich highlights begin to set in.

If relief is often how diagnoses make people feel, what do they incentivize people to do? Become clients of the mental health industry, of course. For the vast majority of disorders listed in the DSM, the recommended solution is a combination of therapy and medication, which can only be dispensed by mental health professionals.

Are therapy and medication good solutions? It’s an important question, but the solution problem doesn’t care. Remember those toe-spacers from Part II. The relevant question isn’t whether they work—they do—it’s whether my cramped toes were actually a problem that needed addressing, or a problem whose remedy would make me happier. The answer to both of these is: not…really.

The Specific Problem of Mental Illness

Mental health experts have a limited view into the reported rise of mental illness because the forces at work—progress, evolutionary mismatch, the solution problem, and so forth—aren’t limited to mental health. But let’s take a minute to revisit the points I made throughout this series and see how they apply to mental illness specifically.

In Part I, I argued that problems are unknown, tolerable, or regular.6 The expanded infrastructure of mental health services has converted many unknown and tolerable problems into regular ones by suggesting that certain experiences are both dysfunctional and capable of being fixed. But what if, as Charlotte Joko Beck suggested, something is only made “unbearable” by the “mistaken belief that it can be cured”? If that’s the case, then raising awareness of mental health issues could have the counterproductive effect of undermining tolerance and souring experience. The thicker the DSM gets, the more of everyday life becomes problematic. And the DSM will stop growing only when every suboptimal way of being has been cataloged—which is to say, never.

Although the DSM has been happy to mint new disorders, it doesn’t have any better track record of solving them. (At least the SnotSucker provided a better solution to the problem of baby boogers, never mind whether one was needed.) Since the DSM’s first edition, hundreds more diagnoses have been added, yet the go-to solutions are still therapy and medication. Don’t get me wrong, plenty of lipstick has been applied to those pigs—new medications and therapeutic techniques are constantly entering the market—but the meds aren’t meaningfully different from those of the 1950s, and no therapeutic orientation consistently outperforms the rest. Thus, the mental health industry continues to lower the threshold for the kind of problems people seek its services for, without improving the solutions. This process can go on forever.

That said, the combination of therapy and medication does offer a proven—though modest—benefit. How should we judge this modest benefit? By weighing it against the costs. Let’s use therapy as our example:

Time and money: Sessions range from $100-$300, generally once a week or every two weeks for many months, even years. Conservatively, the total cost is thousands of dollars for something that, a few generations ago, wasn’t even an option.

Opportunity cost: Individually, learning how to suffer well and grow one’s own network of coping strategies. Socially, the withering of cheap, communal ways to make sense of emotional experience (e.g., religion, neighborhood).

Emergent effects: Bad Therapy is a great book that explores some of therapy’s wide-ranging and unintended effects. For a Living Fossils example, check out The Risks of Avoiding Risk. To the extent that the mental health industry has motivated people to avoid risk—perhaps due to a fear of being traumatized—it has done them a disservice.

The creation of winners and losers: I went to a Pitch-A-Friend a few months ago in which a woman said she wouldn’t date anyone who wasn’t currently in therapy. That’s nuts. And let’s be real, at around $150/session, therapy is a luxury good. So I guess dating has just gotten much more expensive.

“If you build it, they will come”

Remember, the fifth cost of solutions is the solution problem. In the context of mental health, this means that the more infrastructure we build around mental health—therapy, medication, school counselors, diagnoses, accommodations, cultural awareness, reduced stigma, and so on—the more mental health problems we’re likely to see.

I mean, when we send mental health professionals out into the world, what do we expect them to find but—more mental illness?7 And what else are they to recommend but—more therapy and medication? In the same way, missionaries sent into the remote parts of the world invariably found sinful, damned subjects awaiting the lord’s forgiveness and salvation. Hammers can’t help but identify nails—and nail them.

Note that this offers a radically different way of understanding the mental health landscape. If we believe that Problem —> Solution, then the more instances of mental illness that we see, the more services we should provide. But if we acknowledge that Problem <—> Solution, then we would hesitate. In the case where the arrow is heavier from Solution to Problem, we might even scale solutions back.

The default assumption remains Problem —> Solution, though, and this can be seen in a recent article in New York Times, Have We Been Thinking About A.D.H.D. All Wrong?

Though Swanson [lead researcher of the Multimodal Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Study] had welcomed that initial increase in the [ADHD] diagnosis rate, he expected it to plateau at 3 percent. Instead, it kept rising, hitting 5.5 percent of American children in 1997, then 6.6 percent in 2000.

As of 2022, the ADHD diagnosis rate is 11.4%. Is this because more people actually have ADHD than Swanson and others suspected? Maybe. But it probably has more to do with the fact that “if you build it, they will come.”

In the movie Field of Dreams, there were no players before Kevin Costner built a baseball diamond in his corn field. The players would only come—the voice in the stalks promised—once there was a field to play on. In the same way, many problems emerge only after there is an infrastructure to support them. Swanson didn’t underestimate the size of the problem as much as he underestimated the solution’s ability to create more.

Swanson was operating from a Problem —> Solution mindset. He was thinking of children whose parents and teachers would have identified a problem even in the absence of an official ADHD diagnosis or proven treatment options, and he estimated this bunch at around 3%. The Solution —> Problem perspective, however, recognizes that as soon as there’s a structure in place for recognizing, sympathizing with, and rewarding those who claim to have an illness, people will come.

I mean, why not? Kids receive attention and latitude; parents receive permission to administer a drug, guilt-free, that will make their kids easier to manage; and all parties involved receive an explanation and perhaps even an excuse. Who cares if the child actually has ADHD or whether the disorder actually exists?

I am in no way suggesting that individual people are to be blamed or that they are making stuff up to game the system. I’m sure some are, as is true of every system, but really, the problem is much more subtle. The average person is much more a victim of abundance than exploiter of goodwill. In a world of abundance, you see, in which people are so far removed from their ancient problems of hunger, fear, exposure, and so on, people have little clue what a problem is anymore. Or rather, they have no clue what isn’t a problem.

Indeed, the same psychological mechanisms that once helped us make the best of a bad situation—in environments underscored by scarcity—now cause us to flounder in a good one. Perfect so often becomes the enemy of good because good was so often the best our species could do. But not anymore. For every ache, inconvenience, and imperfection, there is a fix in the modern, capitalist world. These imperfections include too much snot in our baby’s nose, a lower-than-ideal threshold for distraction, and—if we take a peek into the new DSM—having bad periods or quitting coffee.

I am not downplaying these experiences, but rather asking what good it does to place them under the purview of the mental health industry. To identify them as Problems instead of just, you know, problems.

We need an outside-the-box way of thinking about mental illness. I agree that progress is a part of the answer—as is evolutionary mismatch, smart phones and social media, and other proximate factors. But we also need an answer that acknowledges that because mental illnesses are not nearly as cut and dried as medical conditions, their self-report is vulnerable to suggestibility and persuasion, especially in the modern first-world where so many basic human needs are taken care of. The answer should also recognize that people can more easily imagine themselves into a problem when its solutions surround them.

When Less is More

The other day, a friend told me about visiting a friend who used a marvelous soap, putting the soap she used to shame. When my friend was next at the store, she had a decision to make. Should she pay double for the marvelous soap, buying herself only a few weeks of happiness in the process, or slink back to her now-underwhelming option? As soon as she became aware of a nicer soap, you see, she was screwed. Yet another instance of a solution backfilling a problem.

But at least that soap was nicer. I am not convinced that therapy and medication are better solutions than whatever people relied upon before. In fact, considering that therapy and medication are patchy solutions that haven’t much improved since their introduction—and that the DSM and other mental health services have ballooned in the meantime—it’s quite possible that the mental health community has created more problems than it’s solved.

That is why I began this series with a quote from John Neale’s The Haunted Man: “…had you read more upon the subject, or less, you might have been cured long ago.” Sad as it is to say about my own field, I tend to think that navigating the world of mental health requires one of two things: either knowing as much as I do—so you can cherry-pick the few worthwhile ideas and discard the rest—or knowing nothing at all, so you don’t end up spending half your life snout-down in endless rabbit holes. The same could be said for many fields, I am sure, but mental health is the one I know best.

My criticisms of the mental health field have probably given some readers the impression that I dislike my job. Nothing could be further from the truth. Indeed, the only person who loves their job more than I do is my friend, who is also a therapist but sees more clients.

The simplest way I can put it is this: I love my job because it lets me build meaningful relationships with my clients. In fact, I often find myself wishing the rest of my life matched the intimacy of a good therapy session. And when my clients improve, it's typically because of the relationship. (Turns out—newsflash!—a deep social bond is pretty healing for a deeply social species.) But the rest? The DSM diagnoses, the medications, the ever-multiplying therapeutic orientations, the canon of mental health theorists from Freud and Jung to Beck and Satir, the saturation of mental health thinking into every corner of life—most of that is nonsense, and I can’t be asked to support it.

Hopefully that explains how I can spend half my week loving my job and the other half bashing my field.

In the end, the majority of people going to therapy could, and once upon a time did, meet their mental health needs in other ways. In many cases, they should meet their needs in those other ways now, instead of capitulating to the mental health industry. I think the rise of self-reported mental illness is at least partly due to the ability of solutions to convince people of a problem, and that if these solutions didn’t exist, people would find other—sometimes better—ways to deal with them. In some cases, they wouldn’t identify a problem at all.

According to Jon Haidt in The Anxious Generation, smartphones and social media are the primary drivers behind the recent decline in adolescent mental health.

I’d like to reiterate that there are exceptions. Someone who resolves chronic pain, or escapes poverty, is indefinitely better off.

Agreeing with the progress answer does not preclude other answers, such as smart phones and social media, or evolutionary mismatch.

If, that is, we ignore the fact that modern people are asked to read more, which is why evolutionary mismatch has to be part of the answer, too. Humans did not evolve to read, meaning someone with dyslexia in pre-literate times would have been blissfully unaware of anything wrong. Dyslexia as a “disorder” only makes sense in light of recent societal demands.

p. 96

By “regular” I mean “normal,” not “recurring.”

Medical specialists are the same. You always have whatever condition the specialist treats.

> Let’s say that based on family stories, you suspect that your great-grandfather had ADHD. (And let’s pretend for the moment that ADHD is real.) He almost certainly would not have been as conscious of his condition as he would today, given that there wasn’t even a shorthand for it. But would he have suspected that something was off? Would he have considered himself different—even less—than others?

> The progress answer says: Yes, he suffered in the shadows of the ignorant society around him. But the solution problem says: Nope, he probably didn’t notice anything at all.

> Remember, the mind must first attend to something, and then classify it as a problem or opportunity, before it tries to solve it. Without much of a mental health infrastructure around him—most notably, without a bona fide diagnosis—your great-grandfather likely had no clue that anything was amiss.

Eh, reading Wikipedia article on History of autism... yeah, autist in the past wouldn't have a concept explaining their issues - they would definitely notice these issues tho.

> [1908AD] Swiss-American psychiatrist August Hoch of the New York State Psychiatric Institute defined the concept of the shut-in personality. It was characterised by reticence, seclusiveness, shyness and a preference for living in fantasy worlds, among other things. Hoch also said they had "a poorly balanced sexual instinct [and] strikingly fruitless love affairs"

or

> A more concise definition of the introverted type was given by Jung in February 1936

> He holds aloof from external happenings, does not join in, has a distinct dislike of society as soon as he finds himself among too many people. In a large gathering he feels lonely and lost. The more crowded it is, the greater becomes his resistance. He is not in the least "with it", and has no love of enthusiastic get-togethers. He is not a good mixer. What he does, he does in his own way, barricading himself against influences from outside. He is apt to appear awkward, often seeming inhibited, and it frequently happens that, by a certain brusqueness of manner, or by his glum unapproachability, or some kind of malapropism, he causes unwitting offence to people...

or

>Autistic attitude. All children in this group remained aloof from their environment, adapt to their environment with difficulty and never fully integrate into it. Cases 1, 2 and 3 immediately become the object of general ridicule among the other children upon admission to school. Cases 4 and 5 had no authority among their classmates and are nicknamed "talking machines", although their general level put them significantly above the rest of the children. Case 6 even avoided the company of children, which traumatized him. The tendency to loneliness and the fear of people can be observed in all of these children from early childhood onwards; they stay apart from the others, avoid playing together, they prefer fantastic stories and fairy tales.

Does it really help to not have a way of conceptualizing such problems coherently?

This is why I tell people I am mildly not autistic. As opposed to my grandfather who was almost non-verbal.